AIMEE TAYLOR, 24, holds photos of two of her five children. Taylor was raised in foster care and is fighting now to have two children who were placed in foster care returned to her. The baby pictured here, Kiersten, now 2, was taken from Taylor by Butler County Children Services and placed in foster care. JAN UNDERWOOD / DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

FOSTER-CARE SYSTEM IN CRISIS

Children often the last to benefit

Difficult kids flood system as government oversight vanishes

By Debra Jasper and Elliot Jaspin DAYTON DAILY NEWS

Published: Sunday, September 26, 1999

Series - Part 1 of 4

Along this stretch of heartland, the fate of many neglected, abused or

unmanageable kids is decided in a one-story, red-brick office building.

DELPHOS - Elida Road is ruler-straight blacktop that slices though rural

Ohio's checkerboard of wheat, soybeans, corn and its newest cash crop:

America's castoff children.

DELPHOS - Elida Road is ruler-straight blacktop that slices though rural

Ohio's checkerboard of wheat, soybeans, corn and its newest cash crop:

America's castoff children.

In 16 years, SAFY has grown from a tiny agency in northwest Ohio to one of the nation's largest private foster-care providers, with branches in seven states, millions of dollars in revenues and control over 1,300 children.

In the foster-care industry, it is viewed as a success story, a thriving and much-needed agency that finds, trains and administers a network of foster parents willing to take in some of the nation's most seriously troubled youth.

But SAFY - and hundreds of agencies like it across the country - operates with limited oversight from government regulators and has little financial incentive to run quality homes. Such agencies can squeeze profits from a system that rewards those who negotiate the highest prices from government agencies and the lowest prices from parents who open their homes to difficult, sometimes hostile, children.

It was in this atmosphere that Bruce Maag, SAFY's founder and president, pleaded guilty to contributing to the delinquency of a minor in 1987. Although Maag surrendered his license to take foster children into his own home, he remains a licensed social worker and continues to operate SAFY with the state's blessing.

The Dayton Daily News also found that Maag and another SAFY official appear to have profited by buying property and selling it to SAFY, the nonprofit corporation they administer.

SAFY's real-estate dealings were fueled by the agency's growth. In 1997 alone, SAFY had $4.5 million in net assets and $538,000 in cash - an enterprise built from an industry increasingly swamped with children.

These children generate income for private, nonprofit agencies such as SAFY, which serve as brokers in a marketplace where the government pays most of the bills.

The children themselves are less likely to benefit than the agencies that place them. With a nationwide shortage of foster homes, many children are taken from abusive or neglectful families only to be placed in unsafe, filthy or dilapidated homes in run-down neighborhoods. Others move from home to home with little time to form lasting relationships.

Steve Mansfield, SAFY's attorney and executive vice president of operations, said the agency has some "spectacular" foster homes, where children are well cared for and parents do all they can. But he also acknowledged it has homes that are not up to par.

`I've been in homes and I walk out of there . . . and I'll ask whoever I'm with, `What the hell is going on?' ' he said.

Cheri Walter, deputy director of the Ohio Department of Human Services, concedes that the foster-care system is deeply flawed. Many agencies and the parents they employ, "are working very hard at loving kids and taking care of them," she said. "At the same time, I'm sure there are some providers doing things less than ethical, and in some cases illegal, and we need to hold them accountable."

Accountability, however, appears to be in short supply.

Consider:

Consider:

* The federal government knows little about the children it spends billions of dollars to support in foster care. In fact, 13 years after Congress ordered states to hand over basic information on these children, 26 states - including Ohio - face penalties for not complying.

* Judges across the country have found what one called `outrageous deficiencies' in the child-protection system. So far, 27 judges in 16 states have issued court orders requiring reforms. A lawsuit in Broward County, Fla., claims agencies routinely place foster children who are sexual offenders into foster homes where they can molest other children.

* Ohio officials acknowledge the state has been `rubber-stamping' the licensing of foster homes and failing to monitor foster agencies. `We absolutely believe the system is broke from the state on down,' Walter said. `We're hearing of too many instances where kids are in unsafe homes.'

* State confidentiality laws have the unintended effect of keeping secret the details of financial mismanagement, abuse and child deaths. Florida and Washington, for example, claim the names of children who die in their care are confidential, making it impossible to verify how they died. And detailing criminal histories of foster parents is impossible in many states because officials won't disclose the names of the people they license.

* Officially sanctioned financial irregularities are easy to find. In two states examined by the Dayton Daily News - Texas and Ohio - officials told the federal government they spent money on foster children when the funds actually went to administration and training. The misreporting allows states to get millions of dollars in federal overpayments.

* The federal government no longer closely monitors the foster-care money it sends to the states. Washington declared a `moratorium' on in-depth audits in 1993, after states successfully skirted federal attempts to get them to repay millions in misspent federal foster-care money. As this moratorium enters its sixth year and costs continue to rise, federal officials are experimenting with friendlier audits to entice states to comply voluntarily.

U.S. Sen. Mike DeWine, R-Ohio, calls the continued lack of oversight "inexcusable."

ENDLESS STREAM OF KIDS

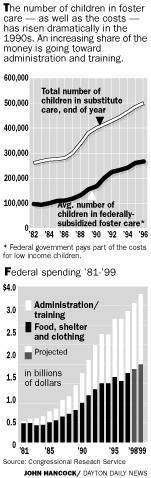

While the government looks the other way, the cost of foster care is rising dramatically.

In 1998 alone, experts estimate that federal, state and local governments spent $9 billion on foster care. With no cap on federal spending, the federal government's tab alone has risen 183 percent in 11 years - even after adjusting for inflation.

"The system has more and more money being pumped into it, and it has just gone crazy," said Maureen Hogan, executive director of Adopt America Advocates, a national group that lobbies for putting more foster children up for adoption. "If this was a different industry, you would hear a hue and cry over what is happening in foster care. Can you imagine if the government put a moratorium on inspecting nuclear power plants?"

The bill for foster care is getting bigger because kids are flooding the system. Between 1986 and 1998, the number of children in foster care nationally rose 90 percent, to 520,000.

The children showing up at the government's doorstep are, in part, a tragic byproduct of the escalating use of hard drugs, particularly the crack-cocaine epidemic in the 1980s.

A 1998 U.S. General Accounting office survey found that an estimated two-thirds of the 84,600 children in foster care in Los Angeles County and Cook County, Ill., had at least one parent who abused drugs or alcohol.

Ann Stevens, spokeswoman for Montgomery County Children Services, said most families where children are removed have multiple problems, but that alcohol or drug abuse is an underlying factor in about three-fourths of the county's cases.

She also said the child-protection system is strained by having to take in kids it was not designed to handle.

"Children Services was set up to help abused and neglected children," Stevens said. Now, it's also being asked to handle kids with more serious problems, youths who are physically aggressive or who start fires, for instance. Placing these children is very hard and very expensive, she said.

The GAO said the dramatic increase in the number of foster children, and the fact that children often stay in foster care for years, also makes homes increasingly difficult to find.

With more kids in the system, and few controls once they get there, more and more children are being placed in substandard foster homes, said Richard Wexler, director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform in Washington, D.C.

"We say we are taking children from danger to safety when many times it is the other way around," Wexler said. "The rate of maltreatment in foster care is far, far higher than generally realized."

Wexler said even by the industry's own figures, foster children make up less than 1 percent of all children but account for 3 percent of the instances of child abuse. He suspects the actual figure is much higher.

"The reason this stuff is so badly under-reported is the child-welfare system never looks closely at what it doesn't want to know," he said.

In fact, Wexler and others say the system provides incentives for foster-care agencies to ignore what happens once a child is taken off the government's hands and placed in a private home.

Here's how it works:

Public agencies recruit their own foster parents to take in younger and easier-to-handle children. Typically, those parents receive less money for accepting children than those recruited by private agencies because the children are easier to deal with.

ACCORDING TO ELIZABETH Clark, who for years ran the CopperCare foster-care agency in Dayton, providers can charge a higher rate by mislabeling a home a treatment home. JAN UNDERWOOD/DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

Although private agencies say these treatment homes specialize in caring for sex offenders, juvenile delinquents and other troubled youth, no national standards exist to ensure that the parents in those homes are equipped to handle such complex problems. In fact, in Ohio, officials acknowledge that licenses are granted almost automatically to foster homes recommended by private agencies.

"A lot of these homes have been mislabeled as treatment homes in order for providers to charge higher rates," said Elizabeth Clark, who for years ran the CopperCare foster-care agency in Dayton.

The federal government, through its Title IV-E program, provides partial reimbursement to local governments for low-income children who are placed in foster care. Agencies collect a per diem - from $15 to hundreds of dollars each day - for every child they take off the state's hands. The more difficult the child, the more money an agency charges. That agency, in turn, generally pays parents about half that money, with the rest going for administration, salaries and other expenses.

Agencies that successfully negotiate low rates with parents can keep a larger share of the per diem.

What they do with that per diem is a matter of growing concern. In Ohio, auditors reviewing the financial dealings of private foster agencies have concluded that the private foster-care industry is rife with fiscal abuse. A state audit of one agency in Columbus found directors using foster-care money to care for their quarter horses, to buy season hockey tickets and to pay for hair salon and tanning visits.

CHILDREN AS PROFIT

State regulators acknowledge that oversight has lagged behind the

industry's rapid growth. SAFY, for example, has expanded from a business

operating out of a house in Lima to a multistate organization with 280

employees. According to SAFY, the expansion has brought some impressive

losses. However, the numbers bear examination.

Although SAFY has its national offices on Elida Road in Delphos, northwest of Lima, there is a separate nonprofit SAFY corporation in each state where the agency operates.

SAFY of Ohio, for example, reported to the IRS in 1997 that it had lost $377,324. There was also grim news from SAFY corporations in Oklahoma, Texas and South Carolina. SAFY of Nevada did eke out a small surplus of $18,000, but that was more than offset by SAFY of Indiana, which lost $134,000.

Submerged in all this red ink is a contract between each of the state SAFYs and the two national nonprofit companies headquartered on Elida Road: SAFY of America and SAFY Holding Co.

The local SAFYs are required to lease all their equipment from SAFY Holding Co. and to have their programs managed by SAFY of America. Thus, SAFY of Indiana, the subsidiary reporting a $134,000 loss in 1997, was billed for $668,000 in management fees from SAFY of America in the same year.

Are the SAFY foster-care agencies in each state losing money? The answer is yes. They reported losing a total of $763,971 in 1997. But in that same year, the agency's IRS records show that SAFY of America amassed a $1 million surplus while SAFY Holding Co. netted $58,000.

The economics of being a foster parent are, in some ways, as convoluted as the accounting systems of the agencies they serve.

In this system, a perverse pecking order develops. Children with the worst problems rise to the top because they carry with them the largest per diems, providing an enticement for some of the poorest parents to take the most troubled children.

Nora Vondrell, director of Daybreak, a Dayton runaway shelter that helps foster children, said most foster parents provide good care. But she said some financially strapped parents are so reliant on the government money they receive that little of it is spent on caring for children.

"Some foster parents will warehouse youths. They are getting $800 a month (per child) and they have seven or eight kids in the home," Vondrell said. "I had one foster parent, she listed an income of three times what I make and her total income is foster parenting."

Children in the system repeatedly tell of living with foster parents who spend money intended for their care on everything from home furnishings to new clothes. As one Dayton foster child explained, "They say they are not in it for the money, but you sit and watch everything get redecorated. . . . The lady's daughter has a new wardrobe and I am still asking for a new pair of shoes."

Wexler believes the system drives out the best parents, who must fight so hard to make sure their foster kids get proper services that they eventually burn out.

"Foster care doesn't pay enough to be a good foster parent, but it pays more than enough to be a lousy one," he said. "If you are a good parent, you still dip into your own pocket to pay for things to make a child really feel like part of a family. But if you are a bad parent and want to milk the system, there is enough money to do that."

Parents and children are both shortchanged in a system driven by money, said one Dayton-area couple, who didn't want to be named because they said SAFY sent out a letter asking foster parents not to talk to reporters.

`Right now, the whole foster-care system is in a quandary,' the father said. "It ceases to be about kids. It's all about profit.'

FOSTER CARE TREK

Although there are no nationwide figures, those involved in the system say

it's not unusual for foster children to live in eight or more homes before

turning 18.

"They move from foster home to foster home, so they don't bond," said Sue Durant, a Piqua foster parent who has cared for foster children with problems ranging from schizophrenia to attachment disorders.

PIQUA FOSTER PARENT Sue Durant, shown with three of her foster

sons, has cared for foster children with a variety of problems and

finds that often times those children are overmedicated.

PIQUA FOSTER PARENT Sue Durant, shown with three of her foster

sons, has cared for foster children with a variety of problems and

finds that often times those children are overmedicated. JAN UNDERWOOD / DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

"Each time she moved, the parents had taken her to the doctor and when I got her she was on nine medications," Durant said, shaking her head. "Now she is on three."

Aimee Taylor, 24, of Hamilton lived in 12 foster homes and with various relatives in three states before she turned 18.

"If you saw the (case file), you'd be like, what the hell are they doing? I was in 18 different homes," she said.

One Dayton girl, whose name isn't being used because she's not yet 18, said she lived with six foster parents in four years.

"One lady kicked me out because her boyfriend tried to do something to me," she said. Next she was placed in a home with five other women, ranging in ages from 15 to 85, who argued all the time. In another home, she said, her foster parent persuaded a physician to put her on an anti-depressant other foster kids in the home were taking.

She rebelled. "I didn't take it because I was convinced that I'm not crazy,' she said.

The nomadic-like trek through foster care is caused, in part, by the children themselves. Parents tell of children who start fires, steal money and threaten their lives. One foster parent recalls a child who laced her contact lens solution with bleach.

"I ended up wearing a patch for a long time," said Elaine Redmond Scott of Dayton. "It was horrible."

Sitting in her living room on Salem Avenue, Scott cried as she talked about her foster children. The boy who laced her contact solution was taken from his crack-addicted mother. The boy's mother, father and an uncle are all in jail.

"These kids . . . are angry with their caseworker who promises them things they don't come through with," she said. "And they are angry because they know their parents don't want them."

Sometimes they're just angry. And when that anger spills out, some frustrated foster parents hand the children back to the agencies that placed them - and those agencies have few choices other than to place them in other homes.

By the time these children turn 18 and "age out" of care, experts say, their ability to cope with life's problems is minimal.

One of the most telling indictments of foster care can be found in a police report from Shawnee Twp. in Allen County. Attached to the incident report about a foster child threatening a social worker is the youth's handwritten note. The boy, who describes being bounced through eight foster homes, struggles to explain why he is so angry.

`Nobody knows how I feel. I've grown up with hate in my heart against everybody. The county took me away from my family. They think they did me a favor but they didn't.

"They just made my life worst.'

Sidebars:

EXECUTIVES DEAL IN CHILDREN AND REAL ESTATEPart 2: Living site turned into party house

Officers buy property, sell it to foster-care agency

By Debra Jasper and Elliot Jaspin DAYTON DAILY NEWS

Published: Sunday, September 26, 1999 ; Page: 17AAGENCY PRESIDENT STAYS IN CHARGE DESPITE CONVICTION

Juvenile justice's confidentiality blanket covers record

By Debra Jasper, Elliot Jaspin; and Mike Wagner DAYTON DAILY NEWS

Published: Sunday, September 26, 1999 ; Page: 18A

Former residents say teens had little supervision in foster-care program