Foster home was party house

Former residents say teens had little supervision in foster-care program

By Debra Jasper and Elliot Jaspin Dayton Daily NewsPublished: Monday, September 27, 1999

Series - Part 2 of 4

SHAWNEE TWP., Allen County - Fort Shawnee Police Chief Rich Rohrbaugh

can't remember whether both teen-age girls were naked, or just one.

He can't remember whether they both ran across the road, or only one did.

But the officer, who came across the girls while on patrol in the early

'90s, does recall that he caught up with one of them hiding in the bushes. And

he's certain they came from an independent-living program operated near Lima

by Specialized Alternatives for Family and Youth (SAFY).

`BASICALLY, IT WAS a big teen-age party. You didn't work. You didn't

do nothing. There was no supervision. Was it a good setting? No. It

didn't do nothing good for anybody.' - Michael Sheets, former

resident of an independent-living program near Lima by Specialized

Alternatives for Family and Youth.

JAN UNDERWOOD/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

"It was a drug house, that's what it was," said former resident Nicholas Morris, now 22. "I did acid there. I did crack, crystal meth and anything I'd come upon. I was surprised by how much freedom we had. We'd sneak out and go party, and we'd sneak people in and party. That's all we did was just party."

Like other independent-living programs that popped up across the country in the past decade, the program run by SAFY, a private foster-care agency headquartered in Delphos, was supposed to teach older foster kids how to land jobs and live on their own.

To that end, SAFY officials say they took teen-age boys and girls they thought would do well in independent living and put them in an old schoolhouse converted into 10 apartments.

The foster children were given an allowance and taught basic living skills, such as managing a budget.

And because the goal was to teach kids to live independently, no supervisor lived in the building.

The results were predictable.

`One night we heard someone screaming, `I've got a gun and I'm going to shoot you.' The police came out of the woodwork,' ' recalled Jim Dempsey, who lived next door. "The police did drug raids. The police were there quite a bit. It was a sad situation."

Dempsey, police, former residents and a former SAFY official describe the independent-living facility as a place out of control. Records at the Ohio Department of Human Services show police were called to the apartment complex 62 times in five years. Police found kids using drugs, drinking, fighting, running away and causing other problems.

SAFY officials acknowledge there were problems at the site but say it eventually was shut down in 1995 because it was `fiscally struggling.'

SAFY's tenuous control over the independent-living program was not the only issue. A Dayton Daily News investigation found the wives of two SAFY officials bought the apartment building and leased it to SAFY for five years before selling it to the agency for more than the original purchase price.

SAFY, it seems, was expected to police itself. The federal government has had a moratorium on in-depth financial audits of foster-care money since 1993. The government also has declined to set standards for how independent-living programs should operate.

Ohio auditors say some of SAFY's financial dealings are beyond their jurisdiction. And officials with the Ohio Department of Human Services say they have never audited an independent-living program's operations. Cheri Walter, the department's deputy director, acknowledged that oversight has been lax but promised reform.

`We do not monitor foster care in this state very well. We recognize that it is not a good system,' she said.

There was, however, one outside agency examining SAFY while the

independent-living program was running its course. In 1993, SAFY applied for

the seal of approval by the prestigious Council on Accreditation, a group that

says it "champions quality service for children." Like most everything related

to foster care, what the council looked at is secret. But with this

accreditation, SAFY could identify itself as an "organization in which

consumers can have confidence."

LAND DEAL LAUNCHES PROGRAM

The independent-living program began with a property transaction involving two people close to SAFY executives Bruce Maag and Ron Jones: their wives.

That SAFY was able to conduct business with the family members of executives shows how much freedom these agencies have to operate. Details of the transaction show something else: Bad programs don't necessarily mean bad business.

Minutes of a SAFY board meeting on Jan. 27, 1990, note that Maag, SAFY's founder and president, and Jones, a vice president, were `in the process of purchasing property at 1130 Shawnee Road, Lima, Ohio, and were proposing to lease the property back to SAFY.

In Ohio, nonprofit corporations are cautioned against doing business with themselves as individuals. However, the board unanimously approved renting the building from Maag and Jones even before the pair had purchased it. The motion to rent the property - a rambling old brick schoolhouse with a small ranch-style house behind it - stipulated that SAFY would pay market rate.

In fact, the property was not purchased by Maag and Jones but by their wives who, according to property records, bought the land for $185,000 just weeks after their husbands had gotten the rental commitment from the SAFY board.

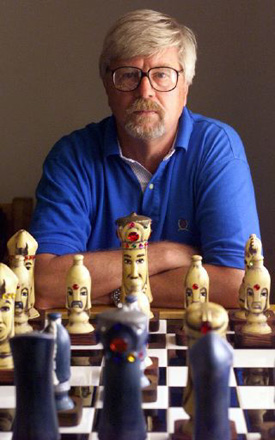

JAN UNDERWOOD/DAYTON DAILY NEWS DONALD ZLOTNIK, former vice president of development for SAFY, resigned from the organization because he claimed, among other things, its president and founder "made money" off of SAFY while children suffered, according to a complaint he filed with the Ohio Department of Development. |

Steve Mansfield, SAFY's attorney and vice president of operations, said SAFY rented the building from the women for $24,000 a year. However, a copy of SAFY's audited financial statement from 1994 says the rent that year was $35,966.

In return for its money, SAFY got a building for its teen-agers that was, according to former residents, dilapidated. The place was a "hellhole," said Morris, who lived there for a year starting in 1994. "There was holes in the walls, stains on the walls from water. It was real dirty."

Dempsey, the neighbor, said the old schoolhouse was divided into tiny apartments, filled with used furniture and had a common living area with a television secured to the wall. "It's no place I would put my own children," he said.

He said one girl in the program got pregnant. Another teen frequently asked him for money. And he ended up giving a winter coat to a resident who was going to school without one.

Despite these conditions, the state never stepped in to shut down the program or even raise questions about how it was operating. Ohio Department of Human Services records show it investigated the independent-living program only after the department received a complaint in 1995 - five years after it opened - from Donald Zlotnik, former vice president of development for SAFY.

Zlotnik told officials he resigned from SAFY in July of that year because, among other things, Maag and Jones "made money" off of SAFY while children suffered, the records show.

State officials said they were leery of Zlotnik's complaint because he wanted the state to hire him as a consultant. Department records also show Zlotnik had written to Maag the week after he resigned threatening to go public about SAFY's problems unless Maag paid him $100,000. If he received the payment, Zlotnik wrote, he would `pack up my computer and leave for the north woods.'

Mansfield called Zlotnik a disgruntled former employee whose allegations are `garbage.'

In the end, the human services department report said many of Zlotnik's allegations were out of the state's purview. However, the investigator looking into SAFY's independent-living program noted that police were concerned that `program youth were buying drugs with the stipend they received.' The report found, `There may be a shred of truth to some of Mr. Zlotnik's allegations,' but many were unsubstantiated.

"I'm not going to say that (the program) was mismanaged," said Ron Browder,

a state human services department deputy director, "but it was run very

loose.'

`NOWHERE ELSE TO GO'

Pat Sheets of Lima said she knows the program all too well. Sheets said that when she first started visiting her son, Michael, there, she thought SAFY ran "a really good program."

Sheets recalled that her son, now 26, who had been in and out of trouble as a youth, was learning how to contact-paper old cupboards and had put together a family photo album.

During subsequent visits, the picture turned bleak. Sheets said she frequently saw beer cans in the trash and eventually discovered the resident manager actually lived in the house behind the complex, so no one supervised the teens after dark. When she found a pair of panties in Michael's room, she learned his girlfriend often spent the night.

"They didn't care if the girls spent the night with guys," Michael Sheets said. He said workers didn't seem concerned about much else, either.

"Basically, it was a big teen-age party. You didn't work. You didn't do nothing. There was no supervision," Sheets said. "Was it a good setting? No. It didn't do nothing good for anybody."

Pat Sheets, who allowed her son to go to the program because he was unmanageable, is proud that her son recently got certified to operate heavy equipment and is turning his life around. But she doesn't credit SAFY.

He left SAFY's program because he was sent to jail for two weeks. He was a juvenile at the time, and he and his mom declined to talk about the charge.

Sheets was not the only person to go to jail from SAFY's independent living program.

Morris, who said he developed a taste for crack cocaine while in the program, is now at Madison Correctional Institution in London.

Sitting in his drab prison garb in a white, concrete block room, Morris said the parties were going strong when he arrived in 1994. "My first day there, I got drunk and puked everywhere," he said.

Morris, who is from Cleveland, ended up in foster care after his mother committed suicide when he was 9 years old. He never knew his father. "There was nowhere else to go," he said.

After moving through a couple of foster homes, Morris turned 16, started high school and got expelled for hitting a teacher. That's when SAFY placed him in independent living.

Morris, who was 17 at the time, said he hadn't used hard drugs before moving to the SAFY apartments.

Strung out on drugs, Morris said he eventually lost his job at McDonald's. So one evening he waited for the resident manager to leave her house behind the apartment building, broke in and stole $105 to buy crack.

Morris was charged with aggravated burglary and sentenced to four to 15 years in prison. Instead of going to prison, he was given probation, and Morris said two SAFY workers tried to help him straighten out his life. But crack was more powerful. He violated his probation and started serving his original sentence.

Morris blames himself for getting hooked on drugs while he was in the program, but he wishes it had been a different kind of place.

"To put teen-agers into a house like that, you know, they really didn't teach us nothing," he said.

Sue Evans, the independent-living coordinator who supervised the resident manager at the Shawnee Road facility, said the program had the usual problems faced by troubled teen-agers. She said teens were sometimes in the building alone because they were supposed to be learning to live independently.

`It was not a group home. It was not designed for intense supervision where somebody is eyeing you seven days a week,' she said. `It was a life-skills development place to help (teens) become independent and function on their own. Therefore, children must experience cooking, cleaning and making decisions.'

Evans said the success of Eric Hunt, a former resident who lived in the complex for two years until 1994, is proof that the program helped kids.

Hunt, a 22-year-old mechanic, husband and father of two, confirmed that SAFY ran an "excellent program."

Did he party there?

"Always," he said. "It was a party house."

The resident manager found it tough "for one person to control a bunch of out-of-control kids," said Hunt, who lives in Lima. He said he used to sneak in a six-pack of beer on Friday nights and drank "a lot" as an underage teen in the house - but only beer. He added that he never saw the other foster kids use hard drugs - just marijuana.

Still, other teens took the partying "to extremes," Hunt acknowledged. "We definitely had the police there.

"For most of them, it was too much freedom too fast."

TEARING IT DOWN TO THE GRAVEL

Nicholas Morris |

To Nicholas Morris, who had watched as SAFY eventually bought new windows and started other renovations on the house, it didn't make sense.

"This is the crazy part," he said. "I ended up moving and the next thing I know, it's torn down after they fixed it all up and everything."

The strange turn of events was driven by SAFY's land deals.

The building renovation began around the time the Council on Accreditation was beginning its inspection of SAFY in 1993. Although SAFY did not own the building, Mansfield acknowledged the agency paid for the repairs.

Mansfield said the accreditation council was not happy that SAFY was renting a building owned by family members of SAFY officials. To avoid a conflict, Mansfield said the SAFY board solicited several appraisals, decided what it would pay for the building and dictated to Mrs. Maag and Mrs. Jones terms of the purchase.

SAFY paid the women $200,000 - $15,000 more than they had paid five years earlier. This was on top of SAFY paying them rent and paying for repairs on the building.

David Nell, chairman of the SAFY board, had no recollection of anything connected with the Shawnee Road property. He said he did not recall the renovation, appraisals or the agency's decision to buy the property from the wives of Maag and Jones.

Mansfield said Nell is mistaken.

With the sale complete, SAFY won the Council on Accreditation's seal of approval, but SAFY didn't hold the Shawnee Road property for long. In October 1995, 10 months after SAFY bought the property, it turned a quick profit, selling the land to the owners of the adjoining properties, a funeral home and an old age home, for $236,000.

Jim Chiles, one of the purchasers, said their first act was to tear down the old schoolhouse.

When asked why, he said: "protection." He feared what new business would pop up next to his funeral home.

While the Shawnee road property is gone, SAFY continues to operate an independent-living program, although now it's a `scattered-site' program, meaning one or two teens live in single apartments at various areas in the community.

Mansfield said independent-living programs are difficult to operate, in part because some teen-agers just aren't ready to live on their own.

SAFY stopped placing children together in an apartment complex for good reasons, he said.

`The difficulty you have with the Shawnee Road property is you are talking about this being independent living, so the kids are by themselves. Any kid you provide . . . with an apartment and they've been in supervision for however many years and, yeah, they are going to cut loose a little bit," he said.

"So can you imagine putting eight or 10 or 12 of them together? Oh, Jesus."

JAN UNDERWOOD / DAYTON DAILY NEWS NICHOLAS MORRIS, who experimented with drugs in a SAFY apartment, walks the grounds of the Madison Correctional Institute, where he is serving a four- to 15-year sentence for aggravated burglary. |

Sidebars:

KIDS GET HELP ON ROAD TO SELF-SUFFICIENCY

Programs teach basics of living alone

By Debra Jasper Dayton Daily News

Published: Monday, September 27, 1999 ; Page: 5AMANY FOSTER CHILDREN SLIP THROUGH CRACKS AT AGE 18

Governments have little followup on what happens when kids are on their own

By Debra Jasper and Elliot Jaspin Dayton Daily News

Published: Monday, September 27, 1999 ; Page: 5A

Part 3:

Trading at the child-care bazaar

Governments, agencies and parents haggle over the price of caring for kids.

By Debra Jasper and Elliot Jaspin - Dayton Daily News

Published: Tueday, September 28, 1999 ; Page: 1A