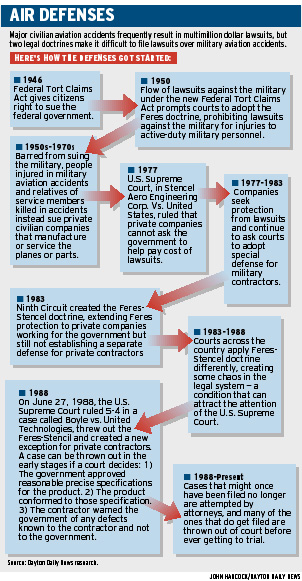

Unable to sue the services, victims of military aviation accidents and their families instead sued civilian companies that made the aircraft, serviced them or had other related contracts.

Unable to sue the services, victims of military aviation accidents and their families instead sued civilian companies that made the aircraft, serviced them or had other related contracts.Private companies began seeking protection, said Miami attorney Joel Eaton, a former Navy fighter pilot and one of the nation's foremost experts in the government contractor defense.

"The industry first mounted a concerted campaign in Congress," wrote Eaton, who once roomed with Capt. Kleemann on an aircraft carrier. "When that effort failed, the industry turned its efforts to the courts, seeking an even greater prize: the abolition of tort accountability altogether."

Defense contractors eventually got what they wanted.

On April 27, 1983, Marine Corps Lt. David A. Boyle was the co-pilot of a CH-53 helicopter that crashed and sank into the ocean off the coast of Virginia.

Boyle, like the three others aboard the helicopter, survived the crash, but Boyle later drowned.

His father sued the Sikorsky Division of United Technologies Corporation, which built the helicopter, alleging the company improperly repaired a part that caused the crash. The lawsuit also criticized the design because the co-pilot emergency escape hatch opened out instead of in, making it difficult to open under water.

A jury awarded Boyle's father $725,000. But an appeals court reversed that ruling, and on April 27, 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in favor of Sikorsky.

"It makes little sense to insulate the government against financial liability for the judgment . . . when the government produces the equipment itself, but not when it contracts for the production," the court's majority wrote.

Under the ruling, a case can be dismissed if a court finds that a contractor built an airplane or other product that conformed to reasonably precise specifications approved by the government, and the contractor warned the government about any dangers in using the product.

"Had respondent designed such a death trap for a commercial firm, Lt. Boyle's family could sue under Virginia tort law and be compensated for his tragic and unnecessary death," Justice William J. Brennan Jr., wrote in his dissenting opinion.

THE RUBBER STAMP OF THE GOVERNMENT Even some critics of the government contractor defense agree that, in theory, private contractors should not have to suffer when they're only building what the government requests. In practice, however, the contractors often know more about what is being built than the government officials who are supposed to be writing the specifications.

The government's approval, Brennan wrote in his dissenting opinion in the Boyle case, can be "perhaps no more than a rubber stamp from a federal procurement officer who might or might not have noticed or cared about the defects or even had the expertise to discover them."

In the Kleemann case, David L. Bourisaw, former section chief for design of the F-18 landing gear, testified that if the government doesn't object to contract specifications, the contractor understands that to be approval.

"Are you telling me approval by acquiescence?" Bourisaw was asked by a lawyer for Carol Kleemann.

"Yes," Bourisaw responded.

Though difficult to document and prove, rubber-stamping has been established in some cases.

On Oct. 7, 1989, an S-3 Viking submarine-hunting aircraft crashed shortly after the plane was catapulted from the USS John F. Kennedy. The pilot, Lt. Douglas G. Gray, tried desperately to recover from a right roll, but the plane wouldn't respond.

"Oh my God! Eject! Eject! Eject!" Gray screamed, just before the plane crashed into the water. Gray and two others were killed.

Relatives of Gray and two others killed in the crash sued the aircraft manufacturer, Lockheed Aeronautical Systems.

Court records show the crash likely was caused by a servo, a device about the size of a small car engine that controls the aileron, the moveable part of the wing that helps control the direction of the aircraft. For years prior to the crash, the plane had problems with its flight control system, court documents show.

Lockheed used a subcontractor to do the work on the servo.

William Burriss, a civilian Navy engineer assigned to the S-3 procurement program and a defense witness for Lockheed during the civil trial, testified that the prime contractor usually exerts a large amount of control over subcontractors' work "with little involvement by the Navy," court records show.

"The development of the servo followed this pattern," the appeals court wrote.

In ruling for the relatives of the dead crew member, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta found that approval of contract specifications requires more than "tacit approval" or a "rubber stamp."

The Navy contract to build the S-3 Viking submarine-hunting airplane included more than 600 pages of specifications, but the court found that Lockheed "presented no evidence that the Navy approved reasonably precise (contract) specifications for the servo."

'THEY GOT AWAY WITH MURDER' Immunity from lawsuits is not a new idea. Local governments have for years protected themselves from certain types of lawsuits by private citizens.

But the Supreme Court decision involving the lawsuit over Lt. Boyle's death did something nearly unheard of in the American legal system: It prevented private citizens from suing private companies.

|

THE REMAINS OF THE wing of an F-18 Hornet lie next to the pickup truck that Rose Emory was driving at the Patuxent River Naval Air Station, Md. Emory, who worked for a civilian company, had just tested the water quality near an ammunition dump when the jet fell directly on the cab of the pickup. NAVAL SAFETY CENTER  | |

|

ROSE EMORY WAS killed on Oct. 1, 1992, three days before her 28th birthday.

ROSE EMORY WAS killed on Oct. 1, 1992, three days before her 28th birthday.RICK MCKAY/COX NEWS SERVICE |

|

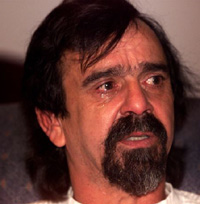

'IF YOU TAKE A HOLE and put it right in your chest, just put a big hole in your chest and have nothing left but a little skin on each side, you find out what it's done to me,' said Harold Emory, describing the loss of his wife.

RICK MCKAY/COX NEWS SERVICE

| |

These cases present another irony in the government contractor defense: When civilians are killed and injured, the federal government can be forced to pay millions while private companies can be protected by the courts.

Harold Emory's wife, a civilian, was killed in 1992 when an F-18 Hornet crashed into her pickup truck.

Emory collected $800,000 from the federal government, but his lawsuit against McDonnell Douglas was thrown out of court before trial because of the contractor defense.

"They got away with murder," said Emory, fighting back tears during an interview at his home in Maryland. "They should be liable for what they've done."

Emory met his wife, Rose, in 1985. She was 21. He spotted her at the Town Creek Marina near his home, followed her to the bathroom and waited until she came out. She called him the next day, and they were together until the day she died.

"I fell in love at first sight," Emory said.

On Oct. 1, 1992, three days before Rose Emory's 28th birthday, she was driving a pickup truck at the Patuxent River Naval Air Station, Md., where she worked for a civilian company testing the water quality on the base. She had just tested water near an ammunition dump when the jet, weighing nearly as much as five African elephants, fell directly on the cab of the pickup she was driving, turning the truck and the plane into burned rubble. The pilot and co-pilot ejected and survived.

The F-18 had arrived at Patuxent River only two months earlier. Before that, it was at Cecil Field, Fla., where it sat for nearly a year without being flown. At Cecil Field, the plane was known as a "hangar queen," a term the military gives to a plane used only as a source of spare parts.

"There's always concern when an airplane doesn't fly for a long period of time," the maintenance officer in charge of the F-18 said in a deposition. "We use it for cannibalization. That is a harsh term but a fact of life. And the reason we do that is because we are short spares."

Chief Warrant Officer Thomas H. Turner testified that he oversaw maintenance for all F-18s at the base, but he had no formal training for repairing several of the aircraft's critical parts, including the flight control system (FCS) suspected of causing the crash.

"Did you ever take any courses on the FCS display?," an attorney for McDonnell Douglas Corp. asked Turner.

"No," he responded.

When attorneys for McDonnell Douglas Corp. interviewed Emory, they asked him if his dead wife had spent money on movies. Whether she cleaned the house. Where she had her motorcycle repaired. How often she did the laundry. What kind of garden she had.

Emory lost his patience.

"You think this piece of paper is my wife, but it ain't," Emory told the attorney. "And you ain't going to bring her back. I know that. The only thing I ever see is paper, man. I would rather see her."

Then the attorney asked Emory, a Vietnam veteran, how much he suffered because of his wife's death.

"If you take a hole and put it right in your chest, just put a big hole in your chest and have nothing left but a little skin on each side, you find out what it's done to me," he said. "It is like cutting a man's heart out and he is still breathing.

"That is about what it has done to me. It's ruined me, man. You know. I mean . . . there ain't no words that explain how I felt."

Emory's case helped established another irony of the government contractor defense: prior knowledge of a problem &-- an aggravating factor in most civil cases &-- by the military can be used a defense, supporting claims by contractors that they weren't withholding warnings. The case also helped expand the contractor defense to civilian companies holding contracts for aircraft maintenance.

"Why is there a double standard?" Emory asked. "If I make a mistake, I'll go before a judge. Why can't I hide behind the government?"

LAWSUITS CAN BE DETERRENTS

Civilian aviation accidents, especially major crashes, frequently result in lawsuits. Many bring multimillion dollar settlements or awards, which in some states can be doubled or tripled in accidents linked to negligence or longstanding, unresolved mechanical problems.

Although not the primary motivating factor, the prospect of paying tens of millions of dollars in legal settlements plays some role in promoting civilian aviation safety, experts agree.

"It has to these days, or you're not going to last very long in the marketplace," said San Antonio attorney Ron Sprague, who defends major airlines and aircraft manufacturers in lawsuits over aviation accidents.

"You have plaintiffs' lawyers running all over the country: self appointed safety officers saying this product is designed badly or that product is designed badly. For better or for worse, their input gets heard by the manufacturer. If they're right, quite often a product is changed."

Though it's impossible to know exactly what effect the threat of lawsuits has on civilian aviation safety, there is little doubt it plays some role in the design, maintenance and operation of aircraft.

Cecile S. Hatfield, president of the Lawyer Pilot Bar Association, recalled a case in which she learned the civilian Federal Aviation Administration had found 22 accidents linked to a problem with fuel tanks in one type of Cessna plane. Following a number of lawsuits, the manufacturer fixed the problem.

"All these lawsuits did make the manufacturer do something about it," she said. "Before that it was not cost-effective to do anything.

"When the accidents started happening and they started getting sued for millions of dollars, they felt they had to do something about it."

Sidebar to Part 5:ANATOMY OF A CRASH - PART 5 |