Contractors protected from suits

Victims have little chance to collect damages

|

©1999 Dayton Daily News

Navy Capt. Henry M. Kleemann became a military superstar the day he shot down a Libyan fighter during a dispute over international waters between the United States and Libyan leader Col. Moammar Gadhafi in 1981.

"This single incident reinstilled pride in being American," U.S. Rep. G. William Whitehurst, R-Va., said in a 1985 entry in the Congressional Record.

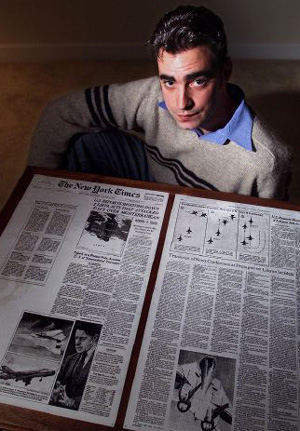

Network television wanted interviews with Kleemann, who flew 128 combat missions and won a Bronze Star for valor in Vietnam. President Reagan later thanked Kleemann's family. The front-page New York Times story about the dogfight was bronzed and hung in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., sharing space with stories of the world's most famous aviators. RICK MCKAY/COX NEWS SERVICE

MICHAEL Kleemann'S DAD, Henry, made front-page news when he shot down a Libyan jet in 1981.

RICK MCKAY/COX NEWS SERVICE

MICHAEL Kleemann'S DAD, Henry, made front-page news when he shot down a Libyan jet in 1981.

"Hank Kleemann was no ordinary individual. . . . Precious few have done as much," Whitehurst said.

Kleemann's death in a plane crash four years later went hardly noticed. But quietly it has made him a new kind of celebrity.

On Dec. 3, 1985, Kleemann was landing an F-18 fighter at Miramar Naval Air Station, Calif., when the right main landing gear failed, causing the tip of the right wing to hit the ground and send the aircraft tumbling. Kleemann was killed.

The Navy had known about problems with landing gear in the F-18 for at least three years. Kleemann's widow, Carol, left with four children to raise on her own, sued the company that made the plane, McDonnell Douglas Corporation. Though she lost the case, her legal battle is required reading for legal scholars and a small, specialized group of plaintiffs' attorneys because her case helped expand a legal doctrine.

Little opportunity to file suit in military aviation

|

"I didn't think it was fair," said Carol Kleemann, whose husband was partially blamed for the accident by the Navy. "I think it kept people from being aware there were problems."

Since the military had for years been protected from lawsuits for injuries to active-duty military personnel under a separate legal doctrine, the government contractor defense narrowed an already small margin of opportunity to file suit over a military aviation accident.

Though the threat of lawsuit hangs heavily over civilian aviation, the military is free to fly its huge fleet of planes and helicopters with little fear that longstanding mechanical problems that go unresolved, or defective parts that should never have been installed, will ever cost them or their contractors a dime.

Military records of Kleemann's crash acknowledge that the primary cause was the right main landing gear and that "similar failures have occurred in this type aircraft over the past several years."

KLEEMANN FAMILY PHOTO

PRESIDENT RONALD REAGAN met with Carol Kleemann and her children (left) after Navy Capt. Henry M. Kleemann's death. Reagan personally thanked them for Kleemann's heroism in shooting down a Libyan fighter during a dispute over international waters between the United States and Libyan leader Col. Moammar Gadhafi in 1981.

KLEEMANN FAMILY PHOTO

PRESIDENT RONALD REAGAN met with Carol Kleemann and her children (left) after Navy Capt. Henry M. Kleemann's death. Reagan personally thanked them for Kleemann's heroism in shooting down a Libyan fighter during a dispute over international waters between the United States and Libyan leader Col. Moammar Gadhafi in 1981.

PACIFIC FLEET, MIRAMAR NAVAL AIR STATION

THE F-18 PILOTED by Kleemann lies upside down at Miramar Naval Station after the right main landing gear failed, causing the fatal crash in 1985.

PACIFIC FLEET, MIRAMAR NAVAL AIR STATION

THE F-18 PILOTED by Kleemann lies upside down at Miramar Naval Station after the right main landing gear failed, causing the fatal crash in 1985. |

"I wanted to correct the problem so other people wouldn't have to die," Carol Kleemann said. "I don't know what else would get their attention."

Thirteen years after Kleemann's accident, F-18s continue to have landing gear problems.

Following a Jan. 26, 1997, incident involving an F-18 from the USS Kitty Hawk, an investigator wrote, "Aircraft has a history of landing gear problems, as do numerous other aircraft."

In less than one month during 1998, three F-18s reported problems with planing links, the same part that failed in the Kleemann crash. A faulty planing link &-- a metal rod attached to the landing gear that helps the wheel turn and fold inside the aircraft wheel well &-- can cause a misalignment, a critical problem during high-speed landings in adverse runway conditions.

On July 17, 1996, a pilot received major injuries in an F-18 crash in Florida that caused $30 million in damage. Navy records show the planing link failed as the jet was landing, but Navy safety officials said the link failed because the pilot made a bad landing approach and slammed the landing gear on the carrier deck.

"We're still concerned about it (planing links)," said Rear Admiral Frank M. "Skip" Dirren Jr., commander of the Naval Safety Center in Norfolk, Va.

The Navy has installed a warning light to address the problem, he said.

"Has it fixed the planing link? Probably not," the admiral said. "But it has mitigated the risk."