So Boeing changed the composition of the metal.

"It was a new process," Ettinger said.

SPECO, once one of the nation's leading gear manufacturers, first used Vasco for aircraft gears in the early 1970s, when it contracted with Boeing to produce gears for a huge military transport helicopter prototype.

"You got to remember that was a development program, and part of the program was to develop Vasco," said Tom Stevens, who worked at SPECO for 30 years and left as manager of contracts when the company went out of business in 1996. "Vasco was supposed to be a material that provided extra strength and extra wear-capability under high temperature conditions."

But the program to build the huge helicopter was canceled, and the prototype never flew.

Later in the 1970s, Litton used Vasco to make gears for another Boeing military helicopter prototype. Although that prototype flew, it was never put into production because Boeing lost the competition to what eventually became the Blackhawk helicopter.

A preliminary report from a 1977 NASA-sponsored test at the Army Research Laboratory in Cleveland found that the teeth of gears made with Vasco fractured during heat treatment.

"The apparent sensitivity of the modified Vasco . . . casts doubts on the practicality of using this material at the present time beyond laboratory and prototype testing," the report says.

Boeing stressed that the 1977 report was preliminary and that the test used by NASA was flawed. In a subsequent report in 1980, NASA engineers modified their earlier conclusion, finding that problems could be eliminated but only under a "closely followed and controlled" treatment process.

The CH-47 Chinook, first used by the Army in 1962, weighs 10 tons and stands as high as a two-story building. The helicopter can carry up to 36 soldiers and crewmembers.

When the program to build the huge transport helicopter was canceled, the Army moved to upgrade its existing transport helicopter, the Chinook, creating a D model. Boeing was selected for the Chinook upgrade and Vasco was used for many of the gears.

"It's no secret that Vasco was a difficult material to process," said SPECO's Stevens. "Processing Vasco required operations not required for other material."

In 1982, five years after the first NASA test, Litton detected grinding cracks in some of the gears, according to an October 1982 memo from Boeing.

The first crash involving the D model came less than three years after the Boeing memo.

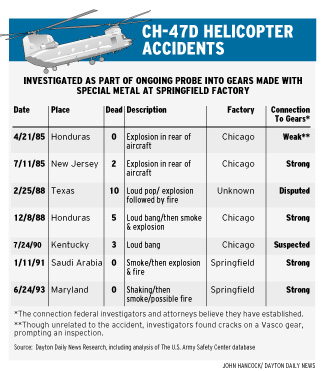

On April 21, 1985, Chief Warrant Officer Alexander Brazalovich was aboard a CH-47D Chinook on his way to a classified mission with an unusually heavy load of fuel and personnel. Ten minutes after landing in Honduras, as the helicopter refueled, Brazalovich knew there was trouble.

"I heard an explosion, and the aircraft started rocking left to right," he recalled during an interview. "I hit my shoulders on the side of the wall. The next thing I know I am on the ground. I was pulled out of the aircraft because I was covered with debris."

The helicopter was destroyed, but the crew escaped with no major injuries.

An Army report found that two gear parts made of Vasco broke into eight pieces each, and Boeing identified what it believed were "grinding cracks" on one of the Litton-made gears. The Army report found that the gear problems did not cause the accident, but the service ordered better inspections to identify cracks in gears.

Brazalovich, who had access to the Army's secret conclusions and findings, said the Army blamed the accident on a bolt that came loose.

"The official explanation didn't match what the maintenance people thought," he said.

Three months later, on July 11, 1985, Boeing test pilot Albert L. Freisner, 48, an Ohio State University graduate, and three other crew members took one of the first CH-47D models for a test flight from the company's plant in Pennsylvania.

A month before the flight, during an inspection of all gears on all CH 47Ds, a Vasco gear on the helicopter was rejected because of what Boeing inspectors believed was a manufacturing defect unrelated to the metal quality.

At 5,000 feet over New Jersey, Freisner heard a loud explosion coming from the rear of the helicopter, where many of the gears and transmission are located. Smoke filled the cockpit. Freisner parachuted to safety, but two other crew members were killed, one hit by a rotor blade as he tried to parachute.

Roby's attorneys and federal investigators now suspect the 1985 New Jersey crash was linked to Vasco gears manufactured by Litton in Chicago.

Boeing officials said the New Jersey crash was caused by a transmission problem, not a gear problem.

"There is no proof it was a gear failure," said Ettinger, Boeing's attorney.

15 DIE IN TWOHELICOPTER CRASHES In 1987, SPECO began making Vasco gears for Boeing at its 70-acre parts factory in Springfield, which once employed as many as 2,200 people.

The following year, on Feb. 25, 1988, a CH-47D from Fort Sill, Okla., was flying at 3,000 feet near Chico, Texas, northwest of Dallas, when the crew heard a popping sound.

"Then there was a loud bang," Sgt. First Class Frank Prather told investigators. "Immediately after the loud bang, the aft, right side of the aircraft was engulfed in flames."

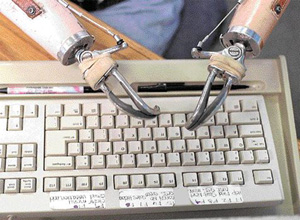

DAN MCCOMB/FOR THE DAYTON DAILY NEWSAFTER LEARNING TO type with artificial limbs, Paul Patricio is now able to manage a tanning salon business out of his Seattle home. 'There was no way I was going to give up,' he said. DAN MCCOMB/FOR THE DAYTON DAILY NEWSAFTER LEARNING TO type with artificial limbs, Paul Patricio is now able to manage a tanning salon business out of his Seattle home. 'There was no way I was going to give up,' he said. |

Paul Patricio lost both of his hands in the fire, and his face and much of the rest of his body were severely burned. He filed a lawsuit against Boeing in 1989, and won a settlement for an undisclosed amount, he said.

"I didn't want to look at myself," Patricio said during an interview earlier this year at his business in Seattle. "At one time, I broke down. I didn't have any hands. I had to depend on people . . . to feed me.

"There was no way I was going to give up."

The military never determined the exact cause of the 1988 crash. Army investigators noted that problems found on a gear were "interpreted differently by several engineers and investigators," but the Army said those problems did not cause the accident.

Boeing officials said the Texas crash had nothing to do with gear failure. Investigators involved in the current Justice Department probe disagree over whether the crash could have been caused by the Vasco gears.

Ten months later, on Dec. 8, 1988, Chief Warrant Officer Randall B. Potter was piloting a CH-47D over Honduras when witnesses heard a loud bang, followed by what appeared to be smoke coming from the rear of the helicopter. As with the Texas crash, the bang was followed by a much louder explosion and fire.

The burning helicopter crashed, killing all five crew members.

The Army at first suspected a high-intensity radio transmission could have caused the accident but later ruled it out.

The Army offered a reward to people in Honduras to locate helicopter parts, and someone brought in a Vasco gear part, which federal investigators suspect may be linked to the crash.

Miami attorney Bob Parks represented the families of the three dead airmen in a lawsuit against Boeing. The company settled the case, he said, but he couldn't recall the amount.

Boeing officials acknowledged that a gear, made of Vasco and manufactured at Litton, failed, but they don't know what caused the gear to fail. They also said the gear failure itself did not cause the crash.

"Something acted on that gear and caused it to fail," Ettinger said.

CRASH DEATHS ALARM CONGRESS The 1988 Texas crash alarmed Congress, and a team of investigators was dispatched to study aviation safety in the Army.

"It's obvious that something was occurring because the birds were falling out of the sky," said Leo Sullivan, one of four U.S. General Accounting Office employees loaned to a Congressional committee for the investigation.

|

The team of Congressional investigators, in a report entitled, "Let the Flyer Beware," found that the Army was "occasionally slow to react to serious aircraft problems, tending to wait until disaster strikes before addressing them." Often, even when the Army does address a problem, the report says, it is a "Band-Aid solution."

Neither the hearings nor the yearlong investigation by the team of investigators dispatched by Congress identified Vasco or the gears made from it as a common link in the accidents.

Concerning the 1985 New Jersey crash, Gen. Donald R. Williamson, who headed the Army Aviation System Command, said during the 1990 hearings that the accident was caused by an "improperly assembled transmission," and he also noted that control rods on the helicopters needed fire protective coatings. The Army, he said, started a "paint application program" to prevent the problem from happening again.

The cause of the 1988 Honduras accident, Gen. Williamson told Congress, was linked to a gear that had failed "due to unknown causes."

"The evidence available indicates a one-time isolated event that will not reoccur and that the fleet is operating under safe conditions," the general assured Congress.

As the Army assured Congress the CH-47D was safe, commanders prepared to ground the helicopter for the seventh time in two years.

'I HEARD A LOUD BANG' On July 24, 1990, two months after General Williamson tried to

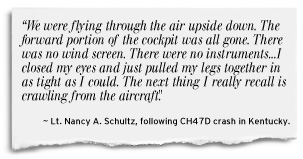

reassure Congress that the Chinooks were safe, Lt. Nancy A. Schulz was flying a CH-47D at night over Fort Campbell, Ky., a 15,760-pound concrete block dangling from a line attached to the helicopter cargo hook.

"I heard a loud bang, and the aircraft started shaking real bad," Schulz told investigators.

"I heard a loud bang, and the aircraft started shaking real bad," Schulz told investigators.

Suspecting the concrete block might be the problem, Schulz pushed the cargo release button. But the power was gone, and the helicopter began to turn upside down.

"We were flying through the air upside down," Schulz said in a deposition for a lawsuit filed against Boeing by the family of one of the crewmembers. "The forward portion of the cockpit was all gone. There was no wind screen. There were no instruments. . . . I closed my eyes and just pulled my legs together in as tight as I could."

Then the helicopter crashed.

"The next thing I really recall is crawling from the aircraft," Schultz said in the deposition. "And I saw. . .a crew member at the time at the nose of the aircraft screaming."

Three of the five people on board were killed. Schultz and another crew member escaped with only injuries.

The family of the instructor pilot, Chief Warrant Officer Dale. W. Tate, sued Boeing, claiming the cargo hook was defective. The court dismissed the case in 1995, but Tate's attorney, Brian Alexander of New York, is trying to get the civil case reopened because, in light of the current federal investigation, he suspects the cause could be linked to Vasco gears, not to the cargo hook.

Alexander said he wanted to get the gears, but he learned Boeing took them. Boeing officials said they purchased the gears, along with other wreckage, from the Army, and Boeing is currently using the wreckage for aircraft training in Philadelphia.

The Justice Department and Roby's attorneys also are interested in the crash.

"The Tate crash sequence is, in many respects, similar to the crash sequence of other Chinooks,"says a request by the Justice Department to get records from Tate's civil case.

Army officials said they have no records showing what happened to the wreckage.

The federal court in Cincinnati has ordered Boeing to allow the Justice Department to inspect certain gears from the wreckage. The court, however, has sided with Boeing in denying the Justice Department access to records from Tate's civil lawsuit.

Boeing officials said the Army blamed the Kentucky crash on pilot error, not problems with the Vasco gears.

BAD GEARS FOUND AFTER SAUDI CRASH One month after the Kentucky crash, on Aug. 23, 1990, Brett Roby, then a newly hired quality assurance inspector at SPECO, officially requested that all grinding on Vasco gears be stopped, a request that effectively blocked production.

"I had people coming to my desk asking me what the hell I was doing," said Roby, who had been at SPECO only six months when he issued the order. "You got to understand, I created a huge bottleneck in the production process, something the culture of this facility doesn't tolerate."

"That's the kind of stuff that makes a guy wake up at night and sweat when you're working on these parts," he said.

Under strong pressure from several officials at SPECO, which was years behind schedule, Roby said, he agreed to lift his order to stop work.

Months later, on Jan. 11, 1991, during Operation Desert Storm, Chief Warrant Officer Robert D. Gardner, a Vietnam veteran, was flying a CH 47D carrying 18 crew members and passengers over Saudi Arabia when he noticed an engine caution light.

As the helicopter was 15 to 20 feet above the ground, smoke poured from an area near an engine, and as the forward wheels touched the sand, the rear of the helicopter exploded.

As the passengers and crew escaped with their lives -- some crawled through broken windows -- the ammunition inside exploded, and fire destroyed the helicopter.

The Army and Boeing blamed the crash on manufacturing defects in a SPECO-made gear. Following the crash, the Army, with the help of Boeing, inspected its fleet of CH-47Ds with SPECO gears.

Of the 360 gears inspected, 20 were identified as having similar problems and replaced.

'THE WHOLE AIRCRAFT SHUDDERED' On June 24, 1993, Donald Defenbaugh was flying one of the CH-47Ds that had cleared an inspection after the Saudi Arabia crash. Defenbaugh, a civilian Army employee, recalled that everyone thought the inspections solved the problem.

"That was the basic understanding in the military: That all the bad ones had been replaced," said Defenbaugh. "The whole aviation community thought it was solved."

Defenbaugh was giving an Army Reserve pilot a test flight over Maryland with four people on board when smoke started pouring from the engine. Then the gears exploded.

"We were only 20 feet off the ground when it happened," he said. "The whole aircraft shuddered in an unusual vibration."

He made an emergency landing, and, though the aircraft suffered substantial damage, no one was injured. About a third of one of the helicopter's gears broke off, Defenbaugh said.

Defenbaugh said the Army never made him aware of the problems with the CH-47Ds, and he recalled that the Army treated his accident as an isolated incident.

"That was my feeling at the time," he said.

Boeing blamed the Maryland crash on a mistake by a SPECO worker trying to remove a sharp edge from a gear surface.

Following the Maryland accident, the Army grounded its fleet of CH 47Ds just long enough to check similar gears in other helicopters. Following the inspection, three more gears were replaced, but Boeing said in court documents that the three gears were replaced "for other reasons."

Meanwhile, Roby said he requested more tests on the gears. It was then, Roby said, he became aware of tests done years earlier showing that Vasco had flaws making the metal susceptible to cracking. The flaws were called continuous innergranular carbide networking (CICN), a problem similar to a crack on a piece of wood or plastic that can cause splitting or cracking.

"I let my managers know we had this condition," Roby said. "We cut it (more gears) up and found the same thing. We had three out of three that were bad. I was starting to get nervous."

Later in 1993, Roby said, he was asked by two high-ranking SPECO officials to stop testing gears. Not long after that, in January 1994, Roby contacted the Defense Criminal Investigative Service (DCIS) office in Dayton, a civilian agency empowered to investigate fraud, waste and abuse in the Department of Defense.

"I told them I didn't think it (CH-47D testing) was being handled properly," Roby said.

In December 1994, the Department of Defense inspector general issued a "Notification of Defective Transmission Gears" concerning the CH-47D. The notification, which outlined the investigation by the Dayton DCIS office, advised military and civilian authorities to take "any action deemed appropriate."

Asked what action was taken in response to the notification, the Army said in a written response, "The U.S. Army continued to fly the CH-47s." The notification, the Army said, was eventually withdrawn.

In the records Boeing filed with the federal court in Cincinnati, the company says the existence of carbide networking in VASCO "was fully disclosed to the Army in 1993." In 1994, the court records say, the Army begin its own analysis of carbide networking in Vasco.

In 1995, Boeing says, the Army concluded that carbide networking identified by SPECO did "not present a safety hazard."

Boeing officials called Roby's claims "unsupported allegations," and they said no gear failures can be linked to Vasco.

"There are thousands of Vasco gears in service today manufactured by SPECO and Litton, and the CH-47 fleet has collectively flown in excess of 600,000 flight hours without mishap due to material deficiencies," Boeing wrote in a prepared response to the Dayton Daily News.

'I HAD A MORAL RESPONSIBILITY' Three months after Roby went to the Defense Criminal Investigative Service, he was laid off from SPECO. Although other employees were also laid off, Roby said he felt his layoff was connected to his complaints about Vasco.

|

On May 22, 1995, Roby filed his lawsuit in federal court in Cincinnati against The Boeing Company Boeing Co. under the False Claims Act.

In September 1996, a test conducted at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base for the Justice Department found "continuous carbide networking...at numerous locations" on one part of the gear. But Boeing said the test found nothing that could have contributed to a gear failure.

The Justice Department intervened in Roby's lawsuit in April 1997.

In February of this year, workers at a British Royal Air Force maintenance center in Scotland found cracks on a gear part, an RAF spokesman said. The part, which is made of Vasco, holds bearings in a gear assembly, or raceway on which the bearings move.

"There is a Boeing representative on site (in Scotland)," the RAF spokesman said. "It was brought to his attention."

The RAF grounded its Chinooks, called Mark 2s by the RAF, on Aug. 7 or 8, the RAF spokesman said. The U.S. Army grounded its fleet on Aug. 9.

"We determined the risk to be very high," said Mark J. Jeude of the Army's Aviation-Engineering Directorate.

Documents filed in federal court in Cincinnati show that in 1991, eight years before the current groundings, Boeing ordered examinations for cracks on bearing raceways. Ettinger, Boeing's attorney, said the 1991 examination concerned a "different anomaly" than what caused the current groundings, and the earlier examination was closed in 1994, after Boeing decided there was "no cause for concern."

On Aug. 27, the Army returned half its Chinook fleet to duty but restricted them to 80 percent engine power.

SPECO, which closed in 1996 and filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy, was a defendant in Roby's lawsuit but settled in 1997, agreeing to pay $20 million to the government and $332,017 to Roby and his attorneys. No money has been paid out because of the pending bankruptcy case, and Roby's attorneys expect that, at best, they will recover only a fraction of the amount.

Litton was purchased by Boeing and is now called Boeing Precision Gears, currently the sole manufacturer of the CH-47 gears.

Under the False Claims Act, the contractor can be forced to pay the government three times the amount lost due to fraud, and an additional $5,000 to $10,000 for each false claim. Roby is alleging 240 false claims, and his attorneys estimate that the government is seeking hundreds of millions of dollars.

Trial on his lawsuit is expected to begin sometime next year.

"I don't expect a settlement," Helmer said.

Roby, who is currently unemployed and living off Social Security for a spine disease, said he doesn't regret what he did.

"It boils down to this: I had a moral responsibility," he said. "I got to shave in the morning. I think they knew they had a problem with the processing of the metal."

Sidebar to Part 2

ANATOMY OF A CRASH - PART TWO

Critical system had history of failure

At the time of the crash, plane had at least 10 outstanding maintenance directives.

Part 3: Oct. 26, 1999

Poor maintenance linked to hundreds of mishaps

Many mechanics inexperienced, overworked