Poor maintenance linked

to hundreds of mishaps

Many mechanics inexperienced, overworked

|

©1999 Dayton Daily News

The tail rotor sat on sawhorses for more than a year before mechanics installed it on the helicopter Lt. Col. Allen E. Oliver and Capt. Robert E. Edwards flew on March 1, 1996.

Thirty-six minutes after takeoff, the tail rotor fell off, and the AH-1W Super Cobra fell 1,000 feet into a Georgia pine forest, killing the two Marines.

NAVAL SAFETY CENTER

INVESTIGATORS LOOK OVER the scene after an AH-1W Cobra fell 1,000 feet into a Georgia pine forest in 1996, killing Lt. Col. Allen E. Oliver and Capt. Robert E. Edwards. The helicopter's tail rotor fell off 36 minutes after takeoff.

NAVAL SAFETY CENTER

INVESTIGATORS LOOK OVER the scene after an AH-1W Cobra fell 1,000 feet into a Georgia pine forest in 1996, killing Lt. Col. Allen E. Oliver and Capt. Robert E. Edwards. The helicopter's tail rotor fell off 36 minutes after takeoff. |

"Two lives were lost."

Oliver and Edwards died because the system used to maintain military aircraft is itself broken.

An 18-month Dayton Daily News examination linked hundreds of incidents, ranging from in-flight emergencies to major crashes, to maintenance errors: work performed by unqualified mechanics, parts installed improperly, engines overhauled incorrectly, aircraft shoddily inspected.

Never-before-released computer records identified "improperly installed" parts in 632 emergencies and accidents occurring in the Air Force between 1972 to 1997. Of those cases, 83 were major accidents, killing 79 people and permanently injuring nearly 200.

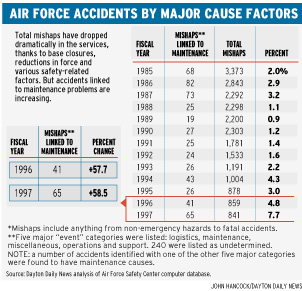

And there are indications the military's aviation maintenance problems are worsening as the services struggle with the loss of thousands of experienced mechanics, aging aircraft, lack of spare parts and global conflicts.

More than 25 percent of the Marine Corps squadron assigned to support the President's aircraft fleet -- typically where the military sends its best mechanics -- consisted of Marines just out of training, says a 1996 study the administration ordered following several incidents involving the White House fleet.

A Sept. 19, 1996, report from the Air Force Audit Agency also found that 107 of the 210 maintenance personnel the Air National Guard listed as fully qualified "had not received mandatory skill-level training on over 1,400 tasks."

The newspaper's computer analysis found that in the Air Force, the only service to specifically track such cases, maintenance-related incidents more than doubled between 1992 and 1997, while the number attributed to other causes dropped by half. In a single year, from 1996-1997, maintenance-related incidents increased 58 percent.

"We're not as skilled as we want to be. There's no question," said Col. Jack Leonard, who oversees aircraft maintenance policy for the Air Force.

SKIP PETERSON/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

LT. KENNETH DUKE, JR. gazes at the air strip at Calender Field in New Orleans where he used to fly F-15s for the Louisiana Air National Guard. Duke was severely injured in 1993 when he hit his head on the cockpit canopy as he ejected from an F-15. He's still unable to speak or move his limbs properly.

SKIP PETERSON/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

LT. KENNETH DUKE, JR. gazes at the air strip at Calender Field in New Orleans where he used to fly F-15s for the Louisiana Air National Guard. Duke was severely injured in 1993 when he hit his head on the cockpit canopy as he ejected from an F-15. He's still unable to speak or move his limbs properly.