|

Oregon's care includes freedom, but also some risks

Options range from self-care to ventilator homes

By Jim DeBrosse© 1999 Dayton Daily News

PORTLAND, Ore. -- Safety or freedom? Which is more important in caring for the health needs of the disabled and elderly?

Answering that question becomes a balancing act for long-term care officials in every state. But in Oregon, perhaps more than in any other part of the country, the balance has swung toward freedom.

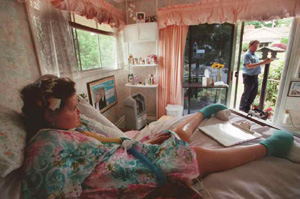

LISA POWELL/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

BARB KENNEDY has lived in New Care Homes, an adult foster care home, for the past four years. This Oregon home is for people on ventilators. If it did not exist, the people living there would have to live in a hospital or nursing home. Each day around noon, her husband, Pat, spends his lunch break with her chatting, flirting or (shown above) putting up a bird house he made for her.

LISA POWELL/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

BARB KENNEDY has lived in New Care Homes, an adult foster care home, for the past four years. This Oregon home is for people on ventilators. If it did not exist, the people living there would have to live in a hospital or nursing home. Each day around noon, her husband, Pat, spends his lunch break with her chatting, flirting or (shown above) putting up a bird house he made for her. |

But then three years ago, after Dentler blacked out several times while away from the facility, officials there declined to care for him.

Now Dentler is in another assisted living facility, Gilman Park, whose management is willing to accept the risk -- and state payment -- for his care.

Dentler can't imagine going back to a nursing home. "I still enjoy getting out and doing things," he said. "And here I can take more responsibility for my own care. I give myself my own baths."

Perhaps nowhere is the Oregon philosophy of health-care choice more dramatically evident than in its ventilator homes.

Five foster homes around the state care for patients who can no longer breathe on their own. Such a high-level of care in a non-medical facility would be unthinkable in Ohio and most other states.

Jeri Hendricks, a former accountant, has five ventilator patients in her foster home in the West Hills area of Portland. Two specially-trained nursing assistants, each certified in up to 12 delegated skilled nursing tasks, are available at all hours to care for the five patients.

With lower overhead, the cost of a ventilator home is much lower than the cost of a nursing home -- $4,000 to $6,000 a patient, compared to $7,000 to $9,000 a month in a nursing home.

'She not only gets the care and attention that's required, she also gets a fair amount of compassion, which is important, really important.' PAT KENNEDY Whose wife, Barb, lives in one of Oregon's five ventilator foster homes.

|

The nurse's aides work 12-hour shifts and rotate every three or four days. "That allows you a lot of time off not to think about (the patients), because these people can go into crisis, for whatever reason, at any moment."

But that hasn't scared off Pat Kennedy and his wife Barb, who is in the final paralyzing stages of ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease. Four years ago, the Kennedys decided they wanted the home-like amenities and extra attention she would receive in a smaller foster care setting.

"The risks are minimal, compared to what she gets in return," Pat Kennedy said. "She not only gets the care and attention that's required, she also gets a fair amount of compassion, which is important, really important. I don't think you can find that in a larger institution."

Prior to his wife's placement in the ventilator home, Kennedy visited a number of more institutional settings, including a 70-bed care center for the disabled.

"I walked out crying. I told myself I would never place my Barbara in a place like that," Kennedy said. "It was very loud. It was very impersonal. There just wasn't a lot of peace and tranquility. Certainly, she gets that where she is now."

Elizabeth Kutza, a professor at the Institute of Aging at Portland State University, said there is a persistent view among the public and health officials, especially in other states, "that you're not going to serve people by putting them in non-medical, non-institutional settings. But talk to any consumer or person living in one of (the alternatives) and they will tell you, 'I will die if I have to go to a nursing home. I want to be here.' "

Kutza said health care officials in other state often are shocked by some of the risks Oregon allows for its elderly and disabled clients in the name of choice.

"There is a real sense that we are doing something kind of reckless and dangerous here," she said. "If you tell people that we have ventilator assistance homes, they almost shout, 'Don't you know that's dangerous? Don't you know you can't do that?'

"Well, we do, and we haven't lost anyone yet."