LISA POWELL/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

CHRIS PETERSON (RIGHT) hugs Marion Kaasa as she serves her dinner. Kaasa is one of the elderly women Peterson cares for in her Lake Oswego, Ore., home. The state of Oregon helps people pay to stay in adult foster homes.

LISA POWELL/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

CHRIS PETERSON (RIGHT) hugs Marion Kaasa as she serves her dinner. Kaasa is one of the elderly women Peterson cares for in her Lake Oswego, Ore., home. The state of Oregon helps people pay to stay in adult foster homes.

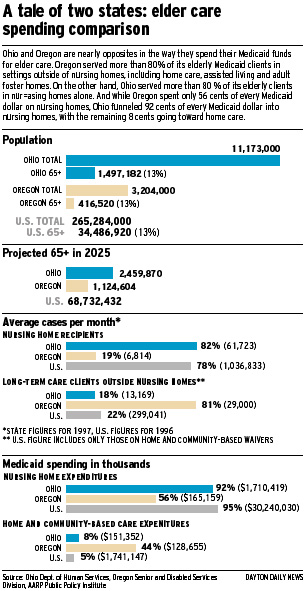

But Oregonians say their system has actually saved the state money by providing cheaper alternatives to nursing homes and by giving family caretakers enough support to head off more costly institutional care.

"We've found that giving families a little money now saves a lot of money down the line," said Mary Lou Ritter, director of aging and veteran services for Oregon's Washington County, just outside Portland.

"We've found that giving families a little money now saves a lot of money down the line," said Mary Lou Ritter, director of aging and veteran services for Oregon's Washington County, just outside Portland.Elizabeth Kutza, a professor at the Institute for Aging at Portland State University, said Oregon's long-term care system hasn't saved money so much as spread the benefits of its spending to a larger proportion of elderly who need help. "What the state was really looking for was to slow the growth (of spending), and it has done that while also serving more people," she said.

Even with the highest minimum wage standard in the country, Oregon spends an average of $901 per elderly client per month. In Ohio, the average is more than $2,000 per client per month, although experts warn it's hard to compare the two states because of differences in size, demographics and services offered.

In addition, Oregon spends another $6 million to help the elderly who aren't Medicaid-eligible, but who need some assistance with in-home care, or for caregivers who need a break from their exhaustive duties. "It's a form of risk intervention -- a way to reach those people who aren't really in our system but who are really risking their health and safety," said Coleen Hoffman, a case manager in Oregon's Clackamas County.

In the early 1980s, Oregon was the pioneer in exploring choices for elderly care and is still the leader in paying for a variety of options, but other states are catching up, including Washington and Wisconsin. Thirty nine states now pay for assisted living and 19 support adult foster homes.

Oregonians insist that other states can, and should, follow their lead, and that there is nothing special about what they've done. "You need a confluence of things, including receptive legislators and strong grassroots advocates to have it really go forward," Kutza said.

"But it's not easy to do. There is the entrenched influence of the nursing home industry, and an entrenched conservative view of a lot of well meaning people that moving from the medical model of a nursing home to more community-based settings will have risks for the elderly."

Oregon's move away from nursing homes began with a grassroots movement of senior citizen organizations that later joined forces and called themselves the United Seniors Cooperative. In the late 1970s, they began to put intense pressure on the Oregon state legislature to offer seniors more choices in long-term care.

"The state bureaucracy wasn't willing to make changes -- not until advocates in the community came into the legislature and demanded change," said Ritter.

Oregonians concede their system wasn't created overnight but rather piece by piece over the last two decades. They insist that other states can do the same. "People outside the state think we're a bunch of cowboys and environmentalists running around in Birkenstocks, and that there's no use trying to do what we've done," Stephens-Tiley said. "But that's not true. If we can do it, any state can do it."

Oregon officials list among the key steps to creating their system:

In the early 1980s, the state applied for and received a waiver from the federal government so that the state could use its Medicaid funds to pay for in-home and community-based services as well as nursing home care. At the same time, it consolidated all of its funding sources and operations into a single agency to oversee and pay for a wide range of services to the elderly and disabled, including food stamps, medical and cash assistance and long-term care.

Soon after, the state created a case management system in which the elderly and their families could go to a single, local office to access all the services in the state's system. Each client is assigned a case manager, who assesses their needs and preferences, matches them to state-funded resources and follows up to make sure their needs are met in the least restrictive setting.

A second piece of legislation that allowed the placement of very frail older persons in community settings was the Nurse Delegation Act. A nurse is able to delegate certain nursing tasks to a non-licensed person if they provide adequate training and regular supervision. The act permits medically stable but frail persons to reside in settings that don't routinely have a nurse on staff, greatly lowering costs.

To help develop alternatives to nursing homes in the 1980s, local officials aggressively recruited and trained caregivers willing to take in up to five elderly persons in their own homes and be reimbursed for their services by the state. Thousands of adult foster homes were created, but the need for stricter regulation soon became apparent. In the early and mid-1990s, the state tightened up its monitoring and supervision of such homes.

In the 1990s, as assisted living facilities began to emerge as a popular choice for long-term care, state and local officials worked out financing schemes with private developers, with the promise that a percentage of Medicaid clients would find apartments in their new facilities. Currently, 30 percent of Oregon residents in assisted living facilities are on Medicaid.

Oregonians needn't impoverish themselves to receive assistance through the long-term care system. Through its state-funded Oregon Project Independence, the state provides home care, personal care, chore services, in-home respite, adult day care and medical equipment on a sliding fee basis to those not eligible for Medicaid. The idea is to help support families coping with the care of loved ones at home to avoid having to place them in a more costly setting.

LISA POWELL/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

CHRIS PETERSON (RIGHT) hugs Marion Kaasa as she serves her dinner. Kaasa is one of the elderly women Peterson cares for in her Lake Oswego, Ore., home. The state of Oregon helps people pay to stay in adult foster homes.

LISA POWELL/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

CHRIS PETERSON (RIGHT) hugs Marion Kaasa as she serves her dinner. Kaasa is one of the elderly women Peterson cares for in her Lake Oswego, Ore., home. The state of Oregon helps people pay to stay in adult foster homes.

|

Davis and others who lobbied heavily for alternatives to nursing homes acknowledge that the explosion in adult foster homes in the 1980s included some that were poorly run. The emphasis back then was on creating alternatives, not discouraging their development with regulations.

"When you go from hundreds to thousands of such homes in just a few years, it's impossible to have all the statutes and regulations you need in place," he said.

In 1988, the Oregon Health Care Association, an organization of about 140 nursing homes in Oregon, accused the state of ignoring "reams" of complaints about neglect and insufficient care in adult foster homes, resulting from undertrained staff.

The accusation triggered a two-week federal investigation later that year. In the end, however, investigators turned up no problems serious enough to threaten a federal pull-out from the state's waiver program, which allows Medicaid to be used for everything from adult day care to assisted living.

"There are areas that need perhaps a little more attention, but there were no horror stories," said Bonnee Butterfield, the lead investigator at the time for the federal Health Care Financing Administration.

Nevertheless, senior advocates such as Davis later lobbied for tighter controls and higher safety standards for the foster home industry, so that by the mid-1990s "we have definitely brought the system around," he said. New regulations require more training for foster home caregivers, better fire and safety alarms and special licensing for those facilities that care for Alzheimer's and dementia patients.

Cote, the state's long-term care ombudsman, said many foster homes still have a long way to go. "Over time, they have taken care of a more and more impaired (group) of elderly. I'm not sure that's a good thing, especially since past studies have shown concerns with quality when foster care providers were asked to take care of more medically complicated cases."

Consumer choice already is changing that picture. Assisted living is becoming an increasingly popular option for the elderly in Oregon, as it is elsewhere in the country, while the adult foster home population is slipping.

In 1997, assisted living and residential care facilities served 8 percent of Oregon's elderly clients while adult foster homes served 15 percent -- a percentage state officials say has been declining since 1990.

In 1997, more of Oregon's elderly (23 percent) were cared for in those alternative settings than in nursing homes (21 percent).

Ritter said the aim of the Oregon system is to evolve as consumer choices change. The next phase in the evolution is to transform the very nature of nursing homes themselves.

A statewide committee called Vision 2000 "is looking to change nursing homes into something that's not a nursing home," Ritter said. "What that is, we're still not sure yet. But you have to keep looking at new alternatives."