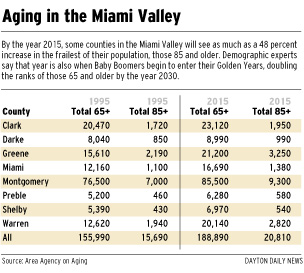

The system of caring for the aged couldn't be failing at a worse time. Seniors 65 and older will soon become the fastest-growing age group in Ohio, doubling in size by 2030. And the frailest and most vulnerable among them -- those 85 and older -- will quadruple in that time.

Half of all baby boomers eventually will spend time in a nursing home, sociologists predict. If the system can't handle the existing elderly population now, what will happen when hundreds of thousands more need services? Who will take care of them?

Half of all baby boomers eventually will spend time in a nursing home, sociologists predict. If the system can't handle the existing elderly population now, what will happen when hundreds of thousands more need services? Who will take care of them?

Nursing home industry representatives and the state officials who regulate the industry defended the quality of care, insisting there is plenty of punishment in Ohio's enforcement system.

Some even said the system focuses too much on penalties and that regulators should work together with homes to improve quality.

Tougher enforcement hurts nursing home quality by making the homes look bad, and thus making it harder to recruit and retain good employees, said Peter Van Runkle, spokesman for Ohio Health Care Association, the state's largest nursing home trade group representing some 760 institutions.

"What do you expect people to think that are looking for prospective employment in this industry if all they hear is the negative?" he said.

Nursing homes get an undeserved bad rap, said Catherine Hawes, a nationally respected researcher at the Menorah Park Center on Aging near Cleveland. The attention focused on bad homes has led to a near-phobia toward all nursing homes, she said, resulting in low expectations that stifle further reform.

"People have unreasonably negative views of nursing homes," she said. "They don't realize that, one, there are some really good nursing homes and, two, you can demand that any nursing home you're in respect your dignity, your privacy and your choices."

Nursing homes also have had to cope with cuts in Medicare, an average of $50 less per day from the federal program that pays for short-term acute health care. Those cuts come at a time when homes are caring for sicker patients discharged earlier from hospitals while also struggling to attract workers and residents against increasing competition, said Ohio Health Care Association President William B. Levering.

"Never before has the business been faced with all of these factors at the same time, and that has put tremendous pressures on operations today," he said.

'CRUISE SHIPS WITH NURSES' Many states, including Ohio, offer a rapidly expanding list of choices for the elderly, allowing them to live at home or in home-like comfort and freedom until they require around-the-clock care.

But the choices are much more limited for those who need both personal care and financial assistance. Their choices are basically two: spend themselves deep into poverty and hope they are selected for subsidized inhome care, or enter a nursing home, where Medicaid will pay the bills.

Unlike many states, Ohio devotes little state funding beyond Medicaid for the elderly. In 1996, Ohio spent about $8 per elderly resident on home and community-based services for those over 65. Illinois that same year spent more than $80 per resident, while Pennsylvania spent $57.

"I'm very frustrated," said Julie Griffie, a Germantown resident who recently placed her 86-year-old mother in a nursing home. "I would much prefer, and I know my mother would much prefer, some kind of assisted living situation, or somebody to come in to her own home. But they cost more than we can afford."

Assisted living is the Cadillac of long-term care in Ohio. Targeting the swelling ranks of the affluent elderly and their families, the glitzy centers aren't equipped to care for the sickest among the elderly, but they can make life very comfortable for those who still have a measure of independence.

Assisted living facilities can feature lobbies with grand staircases and chandeliers, sitting rooms with fireplaces and libraries and private dining rooms with linens and table service. They generally provide residents with their own apartments, furnished in their own way, with private baths and kitchenettes. They can sport in-house clinics, beauty salons, ice cream parlors, drugstores, even banks.

Most offer free transportation and activities nearly around the clock. In some cases, residents can pay extra for their own private duty nurse or therapist, so they can "age in place" without going to a nursing home.

"Cruise ships with nurses," one industry observer calls them.

But like cruise ships, they aren't available to everybody. Assisted living costs anywhere from $2,500 to $4,000 a month, and government programs in Ohio won't cover any of it. That puts assisted living out of reach for most Ohioans. About 36 percent of those 75 and older are either poor or "near poor," according to the Ohio Department of Aging.

Assisted living facilities also are virtually unregulated. Anyone can pay to enter an assisted living center without first undergoing an independent assessment to determine if the facility can properly care for them. The state also lacks licensing standards and staffing requirements specific to assisted living.

"Anyone can hang a shingle outside and call themselves an assisted living facility," said Lisa Heermans, who heads the long-term-care ombudsman office for the Miami Valley.

Lack of state guidelines didn't help Mildred Barrett in 1996.

Barrett, then 94, fell from a second floor window of The Laurelwood, an assisted living facility in West Carrollton, after wiggling her small frame through a gap between the screen and the window frame. She had tried to leave the facility at least five other times in the month before her fall, explaining she had "to get to the highway." Four days before her death, she rammed and bent out another screen with her head, according to a state inspector's report following her death.

The report cited The Laurelwood for failing "to take immediate and proper steps to see that this resident was supervised and received necessary interventions, including, if needed, transfer to an appropriate medical facility." In the end, though, the state took no action against the home. It has no remedies under law short of pulling the facility's license.

Diane Jergens, admissions and marketing director at The Laurelwood at the time, said Barrett had been moved to the second floor and placed on a 15-minute watch by staff just days before her fall because she had tried several times to leave the building from the first floor. Barrett had been at the home only 29 days when she fell, Jergens said. "We were going to have a care conference with her family to decide what they wanted to pursue," she said.

Charles H. Bellmyer, 70, walked away from the Washington Manor assisted living facility in Washington Twp. one Sunday last March and was found drowned in a nearby creek the next morning. Bellmyer, who suffered from Alzheimer's disease, left claw marks on the muddy embankment where police investigators believe he tried to pull himself out of the water.

Ohio Department of Health officials found no reason to penalize Washington Manor for any violations of its license. However, Bellmyer's family filed a lawsuit against the home, accusing the facility of ignoring a physician's recommendation the previous summer that Bellmyer be evaluated for a higher level of care.

Bellmyer, who had relied on his wife, Dorothy Jean, for supervision, remained alone in their one-bedroom suite after his wife was transferred to a nursing home in September 1997. At that point, "someone at Washington Manor should have asked, 'Does this man need a higher level of care?' " said Deborah Hunt, the family's attorney. "Alzheimer's is not a disease that improves. We can only suspect that he got worse as time went on."

The home has denied responsibility in the death in court documents. Terry Duffy, administrator at Washington Manor, declined to comment while the case is pending.

'IT'S BEEN HELL' For 80 percent of the elderly who need assistance, care is not provided in a nursing home or at an assisted living facility. It's provided at home, either by family members or home health aides. But Ohio pays for in-home care only for those elderly frail enough to qualify for nursing home care and poor enough to live well below the federal poverty level.

LISA POWELL / DAYTON DAILY NEWSCHARLOTTE JEWETT is a 65-year-old Trotwood resident who was left a quadriplegic by a car accident in 1962. 'It's been hell,' she said, adding that she was often left stranded in bed during the day or in her lounge chair at night because an agency worker missed an appointment. She switched to a single independent home care aide this summer. LISA POWELL / DAYTON DAILY NEWSCHARLOTTE JEWETT is a 65-year-old Trotwood resident who was left a quadriplegic by a car accident in 1962. 'It's been hell,' she said, adding that she was often left stranded in bed during the day or in her lounge chair at night because an agency worker missed an appointment. She switched to a single independent home care aide this summer. |

"We rarely get the opportunity for a social life," said Renate Lilly, 50.

Recently, the Lillys were forced to cut their in-home assistance by half, from 24 hours a week to 12 hours, because they could no longer afford the extra hours for aides. Even so, it still costs them $1,500 per month.

Renate Lilly has paid a steeper price -- damage to her elbows and shoulder joints from the repeated lifting of her mother. She's receiving cortisone treatments, hoping to avoid surgery on her rotator cuffs. The condition also means she can no longer babysit her 8-month-old grandchild, who has grown too heavy for her to lift.

"If you require outside help (with your parents), and we do, it just becomes overwhelming," she said.

Home health care allows the elderly what they want most: to stay in their own homes as long as they can. But it can be frustrating. Home health aides are in short supply, often underqualified and -- residents complain -- unreliable.

"It's been hell," said Charlotte Jewett, a 65-year-old Trotwood resident who was left a quadriplegic by a car accident in 1962. Until she switched to a single independent home care aide this summer, Jewett said she was often left stranded in bed during the day or in her lounge chair at night, sometimes with her doors unlocked, because an agency worker missed an appointment.

Doug McGarry, executive director of the Area Agency on Aging, said the shortage of reliable home health aides is a national problem, especially with the country in the midst of an economic boom.

"The better employees are gravitating to other areas where the pay is higher and the work isn't as hard," he said.