Frail elderly at mercy of system

A lack of affordable choices, staffing lead complaints

|

and David Gulliver

© 1999 Dayton Daily News

When 80-year-old Grace Blankenship could no longer live on her own, her family found a good alternative: the assisted living wing at Wood Glen Nursing Center in Miami Twp. There, she could move about as she pleased, decorate her room with her own furnishings, bathe herself, eat meals when she felt like it and find fellow residents who could talk about one of her passions: the Cincinnati Reds. Then her money ran out.

Blankenship was put on painkillers. Two weeks later, on the evening of July 4, 1993, she began vomiting and lapsed into shock from severe dehydration. Not until after 6 a.m. the following morning -- eight hours later -- did the home notify her family and physician.

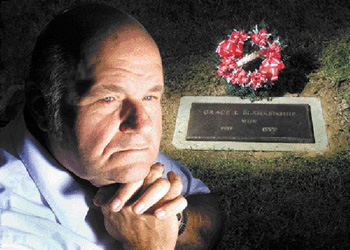

LISA POWELL / DAYTON DAILY NEWSVICTOR BLAKENSHIP SWEEPS his mother's grave at Oak Hill Cemetery before placing a wreath next to it. Blakenship's mother, Grace, died in a long-term elder care facility in 1993 after was battered in her room by another resident. LISA POWELL / DAYTON DAILY NEWSVICTOR BLAKENSHIP SWEEPS his mother's grave at Oak Hill Cemetery before placing a wreath next to it. Blakenship's mother, Grace, died in a long-term elder care facility in 1993 after was battered in her room by another resident. |

She died, at age 81, at 6:40 a.m. July 5, 1993.

"If she'd had enough money, she could have stayed in assisted living, and she would still be alive today," said her son Victor Blankenship of West Carrollton.

Grace Blankenship died because Ohio's $2 billion publicly funded system of caring for the elderly is itself seriously ill.

An eight-month Dayton Daily News examination found the state's frailest citizens are at the mercy of a system that gives companies few incentives to maintain quality homes and limits choices primarily to those who can afford them.

The Daily News analyzed more than 100,000 Ohio Department of Health records on complaints, inspections and enforcement actions over a fiveyear period, examined regulatory systems in three states and conducted more than 200 interviews with government officials, industry representatives, consumer advocates, caregivers and patients and their families.

Among the findings:

Those without means have few choices in Ohio's system of elder care. Of every Medicaid dollar Ohio spends on care for the aged, nursing homes receive 92 cents, leaving most alternatives to those with healthy pensions or bank accounts.

Nursing homes that neglect or abuse patients face few penalties, even if they violate standards repeatedly. Four of five homes the state targeted for enforcement since 1994 escaped fines, and the typical fine was less than what many homes receive in state Medicaid payments in a single day. Fifty-six homes avoided any fines despite facing proposed penalties three or more times in a five-year span.

The nursing home industry is increasingly dominated by for-profit companies that typically have more health and safety violations and fewer staff members per resident than non-profits. The most recent Ohio Department of Health data available show that for-profit homes in 1995 and 1996 averaged more than twice as many serious violations than nonprofits, and they made up a disproportionate number of the state's worstperforming nursing homes.

The state has eased enforcement of health and safety standards even as the number of facilities and programs grow to meet the booming demand for elderly services. The number of inspectors who monitor Ohio's facilities for the aged has dropped by a third since 1995, and overworked inspectors are writing fewer citations. Last year, Ohio long-term care facilities averaged 6.6 citations per inspection, down from 10.2 in 1994. State officials acknowledge that short-staffing has meant less vigilant surveillance.

Despite the growth of assisted living and other alternatives to nursing homes, state regulators have little control over the quality of care in those programs. Ohio is one of 11 states that won't pay for assisted living facilities -- apartments where residents can arrange the services they need -- and it is one of nine states that doesn't license home health agencies. State regulators can threaten to shut down an assisted living facility by pulling its license; they can't impose fines or deny new admissions.

Staffing problems have reached epidemic levels in the elder care industry. Nursing home aides make an average of $8 per hour, and the work can be back-breaking and stressful. A major Dayton-area nursing home operator said qualified help is so hard to find his company is starting a program to import workers from Jamaica. A recent ad in the Dayton Daily News listed these qualifications for a home health aide: Basic First Aid, a current cardiopulmonary resuscitation card (obtainable following a fourhour course through the Red Cross), negative tuberculosis test and reliable transportation. "We're paying teen-agers more to flip burgers than we are to care for our elderly," said Robert Applebaum, associate director of the Scripps Gerontology Center at Miami University in Oxford. "That raises some very serious questions about our societal values."