VOICES OF HISTORY

Tracing the upheaval of the '60s

Series - Part 3

Published: Tuesday, February 16, 1999 ; Edition: CITY ; Section: METRO TODAY ; Page: 3B .

THE STORY THUS FAR: George Cooper became one of the Navy's first black

officers, but after an injury kept him from combat, he has decided to leave a

teaching job in Virginia and come to Dayton. Ellen Lee Jackson, who stayed in

Dayton throughout the war, has watched the city's black commercial district

grow more robust. Yvonne Walker-Taylor has returned to Wilberforce and begun

teaching after spending years in Alabama and Europe. Ned Wood has come back to

Dayton after serving with the Army in Europe to be offered the same menial job

he left behind.

THE STORY THUS FAR: George Cooper became one of the Navy's first black

officers, but after an injury kept him from combat, he has decided to leave a

teaching job in Virginia and come to Dayton. Ellen Lee Jackson, who stayed in

Dayton throughout the war, has watched the city's black commercial district

grow more robust. Yvonne Walker-Taylor has returned to Wilberforce and begun

teaching after spending years in Alabama and Europe. Ned Wood has come back to

Dayton after serving with the Army in Europe to be offered the same menial job

he left behind.But with discontent rising among Southern blacks, the civil rights movement is starting to spread, touching all of their lives.

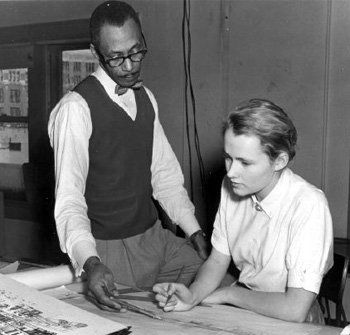

During the '60s, George Cooper began working for Dayton city government as one of its first black directors. He is shown here with an assistant in the planning office. |

ELLEN LEE JACKSON: Fifth Street after the war was very, very quiet. Orderly. There wasn't a lot of confusion. There were two doctors there. One was a dentist and one was a medical doctor. Then there was a shoe shop that was owned by Mr. Rice and then the Dickens boy, when he got grown, had the Dickens Funeral Home on the corner of Hawthorne and Fifth.

Then in later years, The Palace theater was built at the corner of Fifth and Williams. They had stage shows there, too, and on the second floor was a dance floor.

YVONNE WALKER-TAYLOR: We took the news about the Brown vs. Board of Education decision rather mildly. So many things happened that were fruitless, that was supposed to be proponents of "good news, chariot's coming" and we're finally going to get our total freedom. Then it falls down the cracks. I think some of us were pretty skeptical about the issue.

A lot of people, a lot of black people, thought it was stuff that the law was never really going to uphold anyway. So many of the lawyers were just trying to find ways of how to beat us.

NED WOOD: When the strike was over at Frigidaire I came on back and signed up. I went into material handling. I started at 95 cents.

After the strike, blacks could get better jobs at the plant than just janitor. But the strike was really about money.

I stayed at Frigidaire for 30 years.

COOPER: I worked in the house-cleaning business no more than two or three years. Then I got sick. I went to the doctor, and the doctor said, `You can do one of two things. You can get out of the pressure you're in in this business, and live a little longer, or you can stay there and die. Because you're under too much pressure.' I went in the next morning and told Crawford I had to quit.

Dayton had passed an ordinance setting forth standards for housing. And with my background at Hampton, where they taught all the building trades, I had at least a speaking knowledge of all of them. So I took the exam, and got one of the housing inspector jobs.

WALKER-TAYLOR: During the 1960s, I went to teach for two summers down in Columbia, South Carolina, 'cause I wanted to see what it was like to live in the South. Part of it also was to get away from Mama. I was living with a strict mother who didn't allow you to do anything. I'd had two husbands and I didn't want to hear this.

This is what the South was like. I had this beautiful French poodle that a friend of mine had sent me. He was a gorgeous little fellow. I took him with me and I wanted him trimmed. Now, I'm driving a new Cadillac and I've got this miniature French poodle and I want him trimmed. I took him to the little place to get him trimmed and they refused to trim him.

I didn't understand it. It just didn't reach me at all. So in my class the next day, I was talking to my class and I mentioned the fact I took my poodle to this shop and I said, "There must be an awful lot of poodles in Columbia."

And they started "hee-heeing." One lady raised her hand and she said, "Ms. Walker, I understand. They didn't trim that poodle because you said it was yours." I said, "Well, yeah, it is mine."

She said, "I'll tell you what you do. Take it to another one on the other side of town and when you go in, you say, `I'm having Ms. Walker's poodle trimmed and you'd better do a good job on it.''

I drive out there. I was conservatively dressed and in my Cadillac and I take this poodle out and I claim it's not mine, it's my boss's poodle. They took the dog and I was scared to death they would kill it. I was so sorry I did it. I didn't know what to do.

When I went to get my dog, I was so glad to see that dog alive.

JACKSON: I belonged to Bethel Baptist Church, and Pastor George W. Lucas would talk about civil rights. He would try to get the members to understand that your life would be better if the civil rights went through.

WOOD: The first thing I heard about civil rights was Martin Luther King at the bus boycotts. I thought that was a wonderful thing. That was really a good move. It sparked things in Dayton, it really did. They started granting blacks loans. Blacks started registering and voting more, too, after that.

WALKER-TAYLOR: I don't remember much happening in Wilberforce in the way of civil rights demonstrations. We were not under the kind of persecution that the people in the South were. For instance, we could go to Rike's and try on a dress or a hat. The shops around Xenia did not bar you from trying on clothes, so we didn't have that part of the marching that was against department stores.

We had a mixed faculty, black and white, and I just don't recall any times that we were under any kind of duress except that one movie theater in the 1930s. But the restaurants in town, we could eat in all the restaurants and so on, so there wasn't any need for demonstrations in this small community. We were protective, overprotective.

WOOD: They had a show on the radio called People Speak. They had this one guy who called in and wanted to talk. He spoke up and said, `We had a nice home on Brookville. Blacks have moved in, so now we've got to move.'

They called it the white flight. Everytime blacks would move in, signs would go up like popcorn. They started moving out.

Whites ran out of Westwood. And then after Westwood, we invaded Residence Park. Ran almost all of them out of Residence Park. Then we started on Dayton View. Ran most of them out. That was a good deal, too. Some of them had almost like a mansion in Upper Dayton View. Oooh, man, there was some fine homes up there. But they ran off and left them.

The races got along real well in the 1950s and 1960s. Because when we moved in, they moved out. There wasn't any interaction, really.

JACKSON: Oh, I remember when they started moving into what I call Upper Dayton View. Well, if a black person got close to a white person, the white person would move out. Yes, that was very noticeable.

That didn't stop them from trying to get into a different neighborhood.

When they moved out to Jefferson Twp. there weren't too many blacks out here.

COOPER: The housing inspector job lasted about 1 1/2 years. I became a city planner, and then I went to Antioch University to find jobs for students on the work-study plan.

But I came back to Dayton because I had been invited to take a job by the then-city manager, whose name was Jim Kunde. He said, `We do not have any black directors for the city of Dayton. I'd like you to be the first one.'

Jim offered me my choice of four departments if I would come back to work for him. And having something of a background of being the first black to do this, that or the other, I looked on this as another opportunity in my life to further document that blacks are able to do anything anyone else can do, if qualified for the job.

So I elected to come in as director of Department of Human Resources.

WALKER-TAYLOR: I used to go out recruiting for Wilberforce. All the other recruiters were white from white schools all over. We traveled with this group and I was the only black. We went to Georgetown, in Washington, D.C. We tried to go to a restaurant, and one of the guys went up and put our names down. There were about 10 or 12 of us. They didn't see me at first. Then when the table was ready, they said come in.

But they put out an arm and stopped me. They told me, "We don't serve Negroes."

So I looked at the guy and I said, "Hey, guys. Did you hear what he said?" So they went round and round, and ahh, such a ruckus they started raising! So I was afraid that we'd all get arrested so I said, "You all go. I'll just go some place else. But all of them said, "I'm going with you."

So we finally wound up going back to Washington to one of the real nice places in Washington. It's still there.

JACKSON: I remarried in 1965 and I went to Tennessee in 1966 to live. It was a small town and they were just integrating the schools at that time.

It went off nicely there in Harriman. That was the name of the place. People were afraid there was going to be a lot of confusion but it didn't happen that way.

But just before I went, I was at Lucas Furriers and they had just had this disturbance in Clinton, Tenn., just maybe a month or so before I left. All the sales girls would say "Oh, Ellen, aren't you afraid to go to Tennessee? How close is this place to where they are doing all that to where you are going?"

I said, "They say it is real close. They say it is only about 12 miles to where I am going."

But they didn't have any trouble at all in Harriman.

WOOD: I was out of town when the riots happened in 1966. We went to Pittsburgh. When we came back, the liquor stores was closed. I went over there to get me a bottle, because after coming back from a trip, you wanted to get your drink and relax. The liquor stores were closed so we went all the way back to Columbus.

WALKER-TAYLOR: Martin Luther King came to Wilberforce to speak and I remember I was assigned to see him around on campus. I know you're going to ask me the year, and I can't remember it to save my life.

I got an opportunity to talk to him. He seemed so tired, so very, very tired. I asked him, "Aren't you tired," and he said, "Yes." He was a very gentle man and he asked to be let alone.

COOPER: I think most black people perceived of Martin Luther King as basically a savior. I recall joining 80-plus other people and taking two buses out of Dayton to go to the March on Washington. It was one of the most inspiring, electrifying experiences one could possibly have.

To stand there at the foot of that monument and listen to his, `I Have a Dream,' you recognize that there is a person who brings hope, who brings promise, who brings an uplifting spirit to the whole race, with a message that it can be done. And we can do it. And we can do it without violence.

Now when you see some of the things that have been inflicted on black people over the years, to expect a black person to say, `No matter what you do to me, I'm not going to fight back' -you have to have been there to appreciate a thing like that.

WALKER-TAYLOR: Malcolm X never came to Wilberforce. I love Malcolm X but I don't think the president thought much of him. He was a kind of a rebel and a lot of blacks shied away from Malcolm X. I liked his daring. I liked the fact that he'd say, "I'm fighting back."

See, I didn't like Martin Luther King's way, like, `Beat me over the head and I'm going to sit here and let you pour hot coffee on me.' See, I'm not going to do that.

I saw the kids sitting down there in Columbia, S.C., and they'd let people do that, some of them, kicked on top of their heads and things like that in those sit-ins that they had at the 5 and 10. I saw that myself and I thought, `Oh, there'd be no way, oh Lord no, no, I know I would kill them. I would hit them and they'd kill me.'

Malcolm X said, "I'll take so much but after that, no more." And my heart broke when his own people killed him. I just couldn't understand that at all, how members of his group, the Muslims, could have done what they did to him. It just appalled me. But he's still my hero.

JACKSON: I didn't think too much of Malcolm X myself. I didn't like his approach, I guess.

COOPER: I never had any truck with Malcolm X. He had his perspective and his outlook and his following, but it was the kind of outlook, perspective and following that was not for me.

I recall questioning the extent to which Malcolm X had any influence on anything. Malcolm X was just the opposite of Martin. He preached violence and hatred. And that's not the way to go in any set of circumstances.

WOOD: When Martin Luther King got killed, that affected me just as bad as when Kennedy got killed. It was grief. But, you know, both of them in a sense committed suicide.

Martin Luther King went out on that balcony knowing his life was in danger. I would have gone out on no balcony knowing my life was in danger, unless I had one of the helmets on we had in the service. He wouldn't have killed me, shooting me in the head. He would have had to shoot me in the heart.

JACKSON: I thought it was a sad day. But I know that no matter how hard you work to accomplish something, there is always someone in the way that turns up.

| Timeline: Significant events of the 1960's |

NEXT: With the gains achieved in the 1960s, our four octogenarians discuss the status of race relations from the 1970s to the eve of the new millennium. |