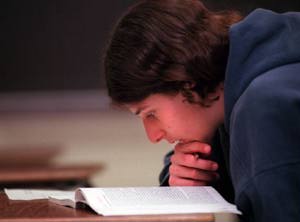

Freshman Josh Wackler studies in the Adjusted Reading Class taught

by Marge Stilwell at Piqua High School.

Freshman Josh Wackler studies in the Adjusted Reading Class taught

by Marge Stilwell at Piqua High School. |

Sidebars:Remedial classes at area colleges One student's success. |

Remedial classes full of kids who never tried to enjoy a book

By John Keilman - Dayton Daily News

Published: Monday, May 4, 1998 - Part 2 of 5

It's five minutes after the third-period bell, and the 15 freshmen and

sophomores in Marge Stilwell's room at Piqua High School have yet to quiet

down. They giggle and gossip, seemingly oblivious to the importance the next

40 minutes will have on their future.

The students are learning to read.

It is the only class of its kind at Piqua High. Stilwell says far more are needed.

`We have a lot of kids who fall through the cracks and fail,' she says. `It's not a pretty picture. But (the school district) needs me as an English teacher, not a reading teacher. The administration says there's not enough money for staff.'

Last year, the state's ninth grade proficiency test revealed that almost 15,000 Ohio freshmen read below their grade levels. For them, high school can be the final chance to master a skill that, more than any other, will dictate their prospects in life.

To succeed, they must overcome a culture many believe doesn't value reading and school programs some experts call inadequate. They must also come to think of reading not as a dull chore but as a valuable, enjoyable experience.

That could be the toughest hurdle of all.

`I guess it's good for you, and you have to learn to do it,' said Herman North, 15, who takes a reading class at Meadowdale High School. `(But) it's not one of my favorite things. If they made it more interesting, I guess it would be better.'

Poor readers advance

Most of the money and attention given to reading programs in America comes in the early years of elementary school, the most critical time in the skill's development.For many children, the lessons don't stick, but poor readers continue to advance until they reach high school. Educators say there's a simple reason.

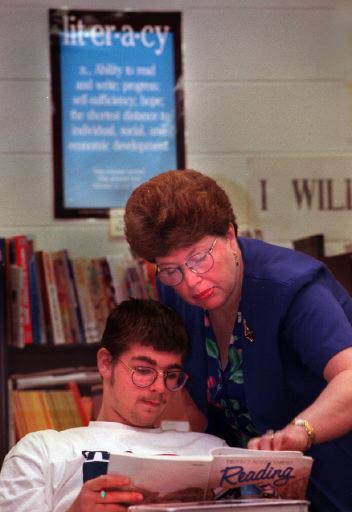

Piqua High School's Marge Stilwell assists freshman John Vastine

on a reading assignment in the Adjusted Reading Class. `We have a

lot of kids who fall through the cracks and fail,' Stilwell said.

`It's not a pretty picture. But (the school district) needs me as an

English teacher, not a reading teacher. The administration says

there's not enough money for staff.'

Piqua High School's Marge Stilwell assists freshman John Vastine

on a reading assignment in the Adjusted Reading Class. `We have a

lot of kids who fall through the cracks and fail,' Stilwell said.

`It's not a pretty picture. But (the school district) needs me as an

English teacher, not a reading teacher. The administration says

there's not enough money for staff.' JIM WITMER / DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

Many school districts, Dayton's included, say they won't promote unqualified pupils for social reasons. But in most cases, they can't keep a student back if the parents don't agree. And whatever a district's policy, there comes a point where it feels compelled to move someone along.

`You don't want a 16-year-old in the eighth grade,' Kendrick said.

But as poor readers progress, they struggle under increasingly heavy burdens. Gay Su Pinnell, who trains teachers at Ohio State University, said that with each passing year, children who haven't mastered reading grapple with increasingly complex material, and fall farther behind their classmates.

Those students frequently become discipline problems, hoping to cover their embarrassment with a veneer of rebellion. For others, the reverse is true: They can't read well because of their trouble-making.

`Someone who's sitting in the principal's office four out of five days a week, they're missing a lot of stuff,' said Jill Holland, coordinator of Miami County's Forest School for disruptive students.

Still, by the time poor readers reach their freshman year, they can sound out words and wind their way through simple texts. The main stumbling block is a limited vocabulary.

Pat Grogan, who trains reading teachers at the University of Dayton, said students can't create meaning from a text if they skip over too many words. To help her teachers understand the problem, she gives them an article on the game of cricket filled with sentences like this:

Wood was caught out of his crease on the first over after lunch. Within 10 more overs, the Australians were dismissed.

`I can read it beautifully. I can say every word in that paragraph,' Grogan said. `But if you were to ask me to retell it, I couldn't do it. I don't have enough background knowledge.'

Expanding vocabulary

High school reading instructors try different methods to expand their students' vocabularies. In a class at Greenville High School, students are expected to memorize 12 to 15 words weekly; a recent list included `despite,' `miserly' and `rash.'

Chaunce Foster (left) and Herman North of Meadowdale High School

work on exercises designed to improved their proficiency. `I guess

it's good for you, and you have to learn to do it,' North said of

reading.

Chaunce Foster (left) and Herman North of Meadowdale High School

work on exercises designed to improved their proficiency. `I guess

it's good for you, and you have to learn to do it,' North said of

reading.

|

`If you read out loud, you get all the words, but if you read to yourself, you skip,' said Mike Kohlhorst, a Piqua High School sophomore who is enrolled in a reading class.

However, teachers say the best way to learn new words is to read voraciously. To encourage reading among students with limited vocabularies, they often turn to unusual literary selections.

At the Forest School, students can peruse hot rod or sports magazines, or fluffy lifestyle publications such as Seventeen - anything that catches their interest and encourages them to read.

One class of books known as `high-low' combines subjects of high interest to teens - sports, celebrities, the supernatural - with simple writing styles. Some books recast the same volumes their peers are reading, such as Huckleberry Finn, using simpler language.

`They don't have the same literary merit as some of the other stories do,' said Mike Puma, director of library services for the bookseller Perma-Bound. ` ... When you're dealing with functional reading rather than for entertainment, you need to take that approach.'

Many teachers also allow their students more choice in their reading material. In one Dayton classroom, an instructor this spring let her students pick between Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and Jane Austen's novel Pride and Prejudice. They opted for Chaucer because they wanted shorter stories, the teacher said.

Such freedom is rare, according to Grogan. She estimated that 90 percent of the nation's high school English classes have a `one size fits all' mentality.

`If everybody reads one book, you risk dropping out many children, because that size doesn't fit them,' she said. `But if you bring in different books, if you allow choice, you're going to pick up a lot of kids.'

Blaming television

Why don't kids read more? Among the reasons teachers cite are jobs, sports, and other distractions. But they are nearly unanimous in their conviction that public enemy number one is sitting in the living room.

Television, they believe, has smothered many a child's ability and desire

to read. Their students would far rather watch the tube, or play video games

or surf the Internet, than pick up a book.

Television, they believe, has smothered many a child's ability and desire

to read. Their students would far rather watch the tube, or play video games

or surf the Internet, than pick up a book.

`The young people today want to be entertained,' said Mona Phillips, an English teacher at Meadowdale High School. When she assigns her pupils a book, `they always wonder, `Is there a movie to it?' It definitely has a bearing on this generation.'

A fellow instructor says TV feeds an appetite for simple plots. Even her advanced students have little taste for complex literature, she said.

However, the research on television's effect on reading is not clear-cut.

In her book, Literacy in the Television Age, Temple University Professor Susan B. Neuman lists 23 studies on the subject. Almost all show little correlation between the amount of television watched and reading achievement. Some even find that TV has a positive effect on reading.

Neuman suggests that family influences are more powerful than the tube.

`There was not much reading before television, and there is not much reading today,' she writes.

Efforts inadequate

While education officials know of reading problems at the high school level, some observers believe they do little to address them.Few secondary schools have specialists trained in reading instruction, and those that do increasingly assign them to mainstream English courses or learning disabled classes, said Alan Farstrup of the International Reading Association.

He added that while many high schools still have classes for poor readers, the teachers working in them may not be experts.

`If you (have) somebody who can get along with the kids and has a background in English, many times they'll be assigned to the remedial reading class,' he said. `That often just doesn't work.'

Others point to Ohio's ninth grade proficiency test, which all students must pass to graduate from high school. Schools, they say, give slow readers just enough attention to pass the exam, then forsake them afterward.

`It's comparable to college, staying up all night to pass the semester exam,' said Richard Vacca, an education professor at Kent State University. `What you remember the day after is zilch.'

He favors an expansive system that focuses on all students, not just the low end. He pointed out that according to one standardized test, only 5 percent of the nation's 17-year-olds reach the highest level of literacy.

Some educators see signs of hope. Grogan noted that teaching candidates must triple their coursework in reading instruction next year to receive an Ohio teaching certificates.

And Lori Bailey, a reading specialist at Miamisburg High School, said her freshmen this year seem more willing to read than past classes. She credited the interest to a new emphasis put on reading in the lower grades.

But among her 60 students, Bailey sees plenty who have completely soured on the activity. Their parents don't read much, and they don't see the need for it. They've also been turned off by too many boring assignments.

`They've never been given the chance to have a good experience with a book,' she said.

Without that, all the classroom drills in the world won't make much difference. Reading proficiency increases only with practice, and students practice only if they're interested.

Meadowdale freshman Chaunce Foster, 15, is like a lot of kids his age. He started the year reading at a low level but realized he must do better. He enrolled in a reading class, paid attention and is making progress.

But he still doesn't like it.

`If it was a sports book, I probably would (read it),' he said. `But probably not just for fun.'

Part 2 sidebars:Remedial classes at area collegesOne student's success. GED: a last chance Learning a trade at the Builders' Academy. |

Back to Part 1 Go to Part 3 Series index |