DAYTON'S BLACK POPULATION

Northwest change may be too much

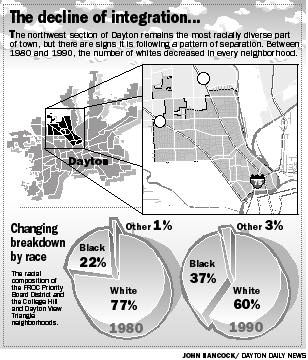

The racial mix, best in the city, is losing white residents.

By John Keilman Dayton Daily NewsPublished: Monday, April 6, 1998

Sidebar to Part 2

In a city divided by color, northwest Dayton is a haven of integration. It

enjoys a robust mix of blacks and whites who, according to one survey, enjoy

the best race relations in the city.

`It seemed really homey," said Natalie Richardson, a 34-year-old black

woman whose family moved to a racially mixed block of the Dayton View Triangle

in 1995.

Between 1980 and 1990, its white population declined by almost a fourth. If the trend continues, Dayton's segregation - blacks on the west side, whites on the east side - will harden.

Some residents and city officials are struggling to preserve the area's interracial mix. But to succeed, they'll have to overcome numerous obstacles, starting with the city's legacy of racial separation.

In the 1920s, Dayton's black population began to swell as thousands of southern blacks arrived seeking good-paying factory jobs. Nearly all settled in a few southwestern neighborhoods.

But black families who did well financially wanted to move out of the crowded area. That meant looking for a house to the west and northwest - in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Jerald Steed, director of Dayton's Human Relations Council, remembers what happened when blacks crossed the color line.

His family moved to the Westwood neighborhood in 1955, when he was 7. It was almost all white when they got there. Within a decade, it was nearly all black.

Between 1950 and 1990, West Dayton neighborhoods became solidly black as whites streamed to the suburbs. But the city's far northwest neighborhoods - those farthest away from the concentration of blacks - still kept most of their white residents.

That may not last.

That may not last.

In 1980, the white population there began to plunge, according to the most recent census data. It dropped most dramatically in neighborhoods with the highest percentage of blacks.

But some believe this isn't a case of white flight. Joseph Watras, a University of Dayton professor and northwest Dayton resident, said whites aren't moving out unusually fast. They just aren't moving in.

He has observed in his neighborhood that people of all races will purchase a house when the seller is white. But when the seller is black, whites rarely buy.

`That would end up in a kind of racial tipping,' he said.

Jim Lindsey, a Grafton Hill resident since 1990, thinks what is happening is income flight. He believes that parents - black and white - are leaving to avoid the Dayton school system.

`Any couple who cares about their children and can afford it, will take the option of going elsewhere,' he said.

Northwest Dayton clearly has a lot going for it. There are plenty of large, well-maintained homes along its leafy boulevards, and property values are increasing. The average home purchase loan in the FROC district, for instance, went from $46,000 in 1991 to nearly $52,000 in 1995.

Then there is the added bonus of harmonious race relations. A University of Dayton study last year showed that people living in the northwest section of town had the `warmest' feelings toward people of other races.

When former Air Force Capt. Jonathan Burgess, who is black, went house-hunting in 1989, Realtors showed him places only in Centerville, Beavercreek and Fairborn. He ultimately chose northwest Dayton because he wanted to live in a `balanced' neighborhood.

There have been previous attempts to steady the northwest neighborhoods. In the late 1960s, a coalition headed by ex-City Commissioner Joseph D. Wine began the Dayton View Stabilization Project. One of the group's suggestions was to implement a quota system: People would not be allowed to sell their houses to a buyer who would upset the black/white ratio.

The idea died quickly.

`They tried all kinds of things,' said Watras, who has studied the integration efforts.

Today, people are taking a more modest approach. One is the Dayton Ambassadors program, where the city takes real estate agents on a bus tour to point out the strengths of local neighborhoods.

`A lot of Realtors don't even want to look within Dayton,' said Pam Miller Howard, an agent who has worked with the program.

Another method comes from CityWide Development Corp. It tries to turn renters into owners by offering loans for mortgage down payments. The theory is that owners will take better care of their homes, making the neighborhoods more attractive and stable.

But the most ambitious idea comes from City Commissioner Mary Wiseman, who wants to reward integrated areas with neighborhood schools.

`The idea of, `Let's find a carrot approach' ... is one we need to keep exploring.'

| Back to Part 2 |

Go to Part 3 |