Elusive equality in the workplace

Expanded job opportunities were a central part of King's vision

By James Cummings DAYTON DAILY NEWSPublished: Tuesday, April 7, 1998

Series - Part 4

Myra McDaniel became a nursing assistant at Kettering Memorial Hospital

seven years ago. She followed in the footsteps of her mother, who worked as a

nursing assistant in a Mississippi hospital when Myra was a child.

But now McDaniel, 37, is a respiratory therapy team leader. She has her eye

on earning a bachelor's degree and eventually would like to work in a hospital

outreach program geared toward improving the health of elderly blacks.

Myra McDaniel is a respiratory therapist at Kettering Memorial Hospital. BILL REINKE/DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

"My parents didn't have the same kind of opportunities I did. But my mother instilled in all eight of us children that we could do whatever we wanted."

Expanded opportunities in the workplace played a key role in King's dream of equality. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened factories and offices to black employees ready for the chance to make a better living.

But in 30 years, blacks have not achieved economic parity.

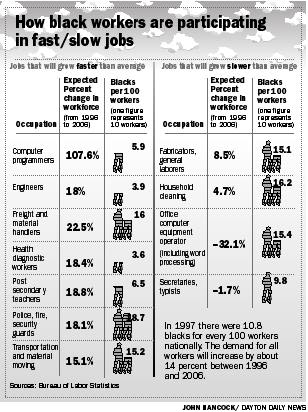

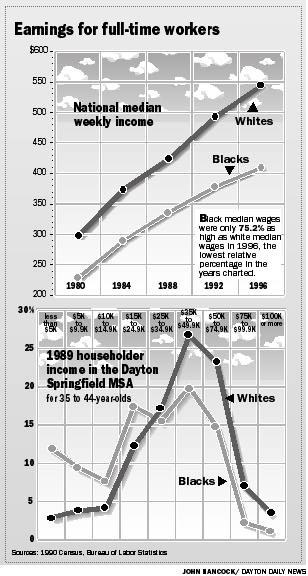

Wages of black workers still lag behind those of whites. For example, the median weekly wage for all white workers nationally was $545 in 1996 compared to $410 for black workers.

And both whites and blacks question the effectiveness of affirmative action programs in hiring and promotion.

In Ohio Poll results released last month, 72 percent of Ohioans opposed giving blacks preferences in hiring and promotion. But the more interesting finding was that blacks surveyed were evenly split, when you take into consideration the sampling error, over whether blacks should be given a hiring preference.

The message to young blacks: Don't count on special treatment in the future. Like McDaniel, blacks seeking good jobs or promotions must depend on their own resources, like going back to school to update their skills.

Tuition reimbursement

McDaniel moved to the Dayton area about eight years ago after traveling around the country with her husband, who had been in the military. McDaniel, who worked as a nursing assistant off and on since high school, got a job at Kettering Memorial Hospital about a year after coming to town.

She picked Kettering in part because of its tuition reimbursement program.

"I had a strong desire to be a respiratory therapist," McDaniel said. "My

mother was a very giving, helpful person, and she had encouraged all of us

toward jobs where we could be of service to people."

She picked Kettering in part because of its tuition reimbursement program.

"I had a strong desire to be a respiratory therapist," McDaniel said. "My

mother was a very giving, helpful person, and she had encouraged all of us

toward jobs where we could be of service to people."

With Kettering's support, McDaniel graduated from the respiratory therapy program at Sinclair Community College. Within two years of her graduation, the hospital promoted her to a team leader in her department, a position in which she earns about $30,000 a year.

"The Lord blessed me with this job," McDaniel said of her team leader position. More area blacks are heading back to school for advanced training. For example, between fall of 1991 and fall of 1996 the number of blacks enrolled in graduate courses at Wright State University jumped 40 percent from 167 to 235.

McDaniel is one of three black respiratory therapists among a staff of more than 100, and she advanced more quickly than others in the department. She feels some believe she got her promotion because she is black.

"When I first started in the job I have now, there were people who were waiting for me to fall," she said. "It could be racism, or it could be jealousy, but there are little battles that you have to fight every day."

Frank Perez, Kettering's president and CEO, said more than 10 percent of the approximate 3,000 employees that work at Kettering Memorial Hospital, Sycamore Hospital and the Kettering College of Medical Arts are minorities and most of them are black.

The hospital sits in a city in which black residents comprise less than 1 percent of the population. But the hospital board asked Perez to increase the staff's diversity when he was hired four years ago, he said. They want to help train then promote more minorities from entry-level jobs into professional and managerial positions. As for McDaniel, her next career move is to add a four-year degree.

"And I'm praying that I'll be able to buy a house for my family in the near future," she said.

Expect advancements

Blacks and other minorities hold jobs at many levels in area companies including spots at or near the top - which is in stark contrast to 30 years ago. Mervyn Alphonso, a black man born in Guyana, for example, is president of KeyBank's Dayton district, and he has three black vice presidents: Gary Roan, Curtis Gregory and Al Butler.If you want to move up quickly in your company, some say you need to expect advancement, and then gear your actions toward achieving it.

Following Gen. Kenneth Eickmann and Gen. Joseph McNeil is Sharon Coleman Jones, protocol chief at the Aeronautical Systems Center at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. BILL REINKE/DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

Jones recalled how an older black co-worker once said Jones would never be allowed to head protocol because the protocol chief must work with foreign officials who might not want to deal with a black woman.

"I guess I somewhat disagreed with her," Jones said. "I mingle pretty well with people from all kinds of backgrounds. And I try to stay on the positive side. I know I can handle things."

Jones' first contact with the base occurred when she was recruited as a public relations trainee 21 years ago. Wright-Pat at the time looked for talent at schools with large numbers of minority students, and Jones attended historically black Spelman College in Atlanta.

Jones' father was a non-commissioned officer in the Navy, and the family cobbled together scholarships, grants and lots of loans to get her through undergraduate school.

Jones said her recruitment at Spelman was the last time race played an obvious role in her career. Being black, she said, has been neither positive nor negative in her working life.

"There are times when people run into barriers because of their race or because of their gender, but for me that hasn't happened," she said.

Jones started in the public affairs department writing articles about programs and activities at Wright-Pat for base publications. She earned a master's degree in communications at the University of Dayton while working at the base.

Now she plans programs for high-ranking visitors to the base and organizes events such as retirement parties. Jones lives in Beavercreek with her husband and two children and plans to continue her career in federal service. Currently she holds a rating of GS14, which pays $65,473 to $85,112 a year, according to base officials.

Base personnel officer Michael O'Hara said the federal government was a

pioneer in creating a diverse workforce in the 1940s and 1950s and continues

to be a leader today. But he said the focus has shifted from recruiting new

minority employees to retaining a mix of minorities at all job levels, given

government downsizing.

Base personnel officer Michael O'Hara said the federal government was a

pioneer in creating a diverse workforce in the 1940s and 1950s and continues

to be a leader today. But he said the focus has shifted from recruiting new

minority employees to retaining a mix of minorities at all job levels, given

government downsizing.

At Wright-Pat, black males comprise 3 percent of the professionals - engineers, contract negotiators, etc. - and black females represent 2.2 percent.

In administrative jobs - like personnel specialists, computer specialists, or budget analysts - Wright-Pat's percentages for black males and females are 5.2 and 7.1 percent respectively, well above the national averages.

Jones knows she owes her own rise at Wright-Pat, in part, to those who paved the way before her. Her charge is to smooth the road for others behind her. "I remember a speaker said once you have to remember whose shoulders you're standing on. I feel very blessed and very thankful for what I've accomplished, and I know I couldn't have done it without the help of blacks who came before," Jones said. "Now I know you have to reach back and help along the others who come after you."

In dad's GM footsteps

The Shepherd brothers - Dwight, 40, Craig, 38, and Marvin, 33 - all got their first jobs at local General Motors plants based on the recommendation of their father Ezekiel Shepherd, 66.Dwight Shepherd already has 21 years experience at GM and expects to continue working for the company another nine years to build up retirement benefits.

But he worries his son won't get the same opportunity he had.

"What plant I retire from might be the question," said Dwight, who is a quality operator at Delphi's Wisconsin Boulevard plant. "All the plants we work in are on the block. They could be sold, and we might have to move."

For thousands of black blue-collar workers, GM provided a middle-class lifestyle. Working on the line and getting overtime paid for many homes, cars and college tuitions.

But shifts in the Dayton-area economy have impacted blue-collar workers.

John Weiler, director of the University of Dayton's Center for Business and Economic Research, said manufacturing jobs, such as those at GM, accounted for 42 percent of the local workforce in 1968. Now they make up about 21 percent of the workforce.

And workers taking factory jobs today don't earn nearly the pay and benefits that were available 10 or 15 years ago.

For several decades, the majority of GM's blue collar workers in assembly and parts factories made $15 to $20 an hour, depending upon their seniority.

But the days of making $20 an hour for 30 years in auto factories are over at GM.

Three GM plants in the Dayton area already have accepted three-wage scales, which pay new workers about $8 an hour. Under three-tier systems, workers must wait longer to receive full health benefits and won't reach top scale for at least 10 years.

The chance to work at GM seemed too good to pass up for the Shepherds.

"It was kind of awesome to me," said Dwight Shepherd of his first GM job. "I had worked at a fish and chips place before but I never had had a good job. I never expected to work at GM right out of high school."

Craig Shepherd said he worked as a security officer after finishing high school and serving four years in the Army. He applied for training as an Ohio Highway Patrol officer, but GM called first. He's been an assembler at GM for the last 12 years. He works at the Delphi Chassis Kettering plant

Dad Ezekiel Shepherd retires this month after 45 years at GM. He started by doing custodial work and retires as an operating job setter, a step below supervision.

None of the younger Shepherds want to become supervisors or administrators.

But the skilled trades - carpentry, electrical, plumbing, tool making - are alluring. It's just that the Shepherds are not sure they'll ever be admitted to training programs for those jobs.

They said white-dominated unions control entrance into the apprenticeship programs that train skilled tradesmen, and blacks are rarely offered equal chances.

"You really have to know somebody who is one (a skilled tradesman) before you get in," Craig Shepherd said. "It's strange to me that some new hires, new white hires, are getting in there so quickly."

Representatives of the unions at the Shepherds' plants did not return phone calls, but GM officials said they feel entrance into training programs have been equitable.

GM officials said about 11 percent of the company's skilled trades workers nationwide are minorities, compared to 22 percent of its overall workers being minorities. Economist Weiler said the problem the Shepherds mentioned may ease as time passes. He said unions in general are becoming less powerful and more workers are getting their skilled trades training through community colleges instead of unions.

"In a way that's an advantage for blacks," Weiler said. "The `Good Old Boy' system in unions that sometimes excluded blacks is not as important as it once was."

Ezekiel Shepherd works at the shock absorber line at Delphi Chassis. Three of his sons have followed him to work at GM. BILL REINKE/DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

Sidebars to Part 3:

NO JOB, FEW PROSPECTS

Unemployment rates for blacks here double that of whites.HE TURNED FRUSTRATION INTO MOTIVATION

A Dayton man headed WPAFB's equal employment opportunity office.Part 4: Where are Dayton's black leaders?

Thirty years after the death of the nation's legendary civil rights leader, Dayton's black leadership finds itself challenged by the very benefits that blacks reaped from the civil rights movement.