`It's my fault where I am. I know that I'm the biggest procrastinator in the world,' said Steven Broyles, shown standing on the grounds of the now closed Jackson Elementary School. He works as a substitute custodian for Dayton Public Schools. |

By Charlise Lyles Published: Sunday, April 5, 1998 |

`Fairness, to me, is giving me a chance to come in and show what I can do,' said Irvin (Smitty) Smith. |

Like many blacks across the country, the two friends were anxious about opportunity.

Would Broyles get to do more at GM Kettering than mop up oil as a janitor?

Would Smitty's bosses at an engineering firm be fair to the new apprentice, one of its first black hires?

Then a rifle bullet tore through the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s neck in

Memphis. At that moment, the two friends stood on the threshold of King's

dream of equal opportunity designed to open doors for millions to climb out of

poverty and into the middle class.

Then a rifle bullet tore through the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s neck in

Memphis. At that moment, the two friends stood on the threshold of King's

dream of equal opportunity designed to open doors for millions to climb out of

poverty and into the middle class.Smitty managed to seize the opportunities. Broyles somehow missed them.

Today, Smitty, 50, is a stockbroker with a Yale degree. He makes about $90,000 annually, he says.

Broyles, 49, teeters on the edge of the underclass as a substitute custodian for Dayton Public Schools. He is paid about $15,000 a year.

For weeks after King's death, up and down Germantown Street, Smitty, sporting an Afro and brimming with moxie, and Broyles, soft-spoken with a close-crop cut, debated.

King `was doing it the right way, peaceful without riots," Broyles insisted.

But to Smitty, "Black Power," the rhetoric of militants Huey Newton and Stokley Carmichael, made sense. "You can't just let somebody whip you," Smitty said.

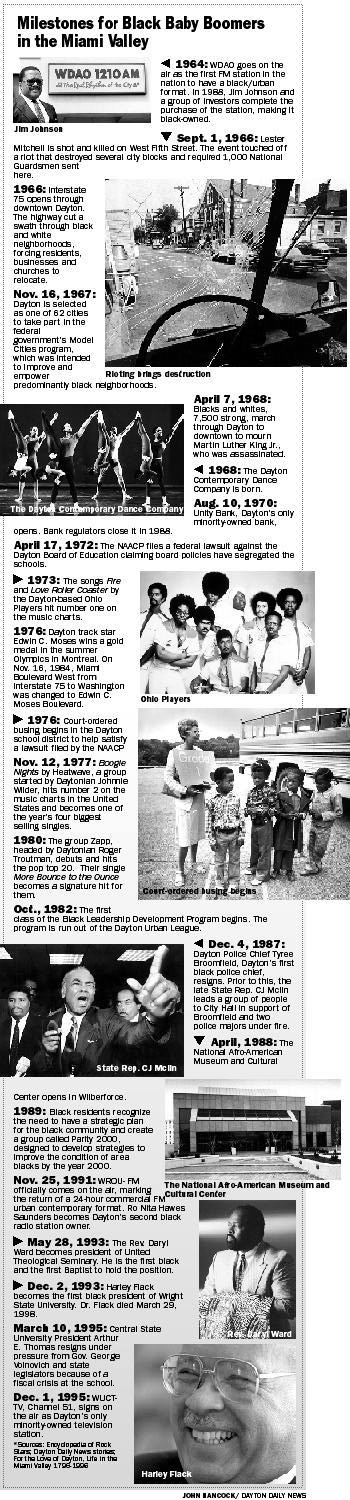

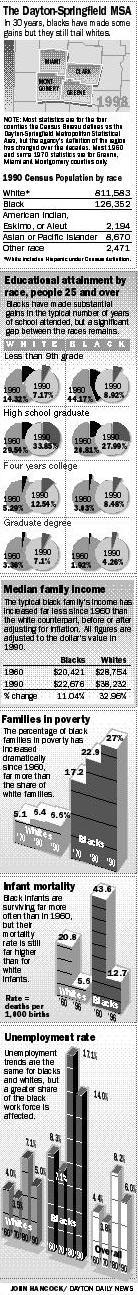

An estimated 9.2 million black baby boomers, ages 34 to 52, were the targeted beneficiaries of civil rights initiatives, enjoying access, via government assistance and intervention, to more educational and employment opportunity than any other generation of blacks in the nation's history. In the Dayton-Springfield MSA, there are 34,479 black baby boomers who experienced the same benefits.

The infusion of affirmative action, anti-poverty programs, court-ordered busing, and public and private minority scholarships has helped to nearly double black middle class households with incomes of $50,000 or more. Between 1970 and 1996, the percentage jumped from 11.5 percent to 19.8 percent nationwide, the U. S. Census reports.

Yet 23.1 percent of black households earned $10,000 or less, census 1996 figures show.

Irvin `Smitty' Smith works as a stockbroker at

The Ohio Company.

Irvin `Smitty' Smith works as a stockbroker at

The Ohio Company. DDN photo by Bill Reinke |

Broyles' father was a jailhouse janitor. Today, Broyles sports Tommy Hilfiger T-shirts to his evening job as a janitor. Puffing an Alpine cigarette, he is comfortable and confident about who he is and who he is not. He has worked hard, and Friday is always pay day.

Though each started from the same place, their lives illustrate how two men, who moved to manhood during one of black America's most crucial periods, took divergent paths - one cashing in on opportunity, the other missing the chance.

Cub Scout buddies

In 1958, at age 10, color brought them together in Cub Scout Troop No. 222, the only Cub Scout troop in town for Negroes.Quinton Smith, a South Carolina sharecropper who came to Dayton looking for factory work, believed scouting would give his boy Smitty grit, sharpen him. Robert Broyles, who migrated from Greeneville, Tenn., had the same notion.

Steven Broyles works as a janitor at Cornell Heights Elementary

School.

Steven Broyles works as a janitor at Cornell Heights Elementary

School.DDN photo by Bill Reinke |

"I pushed them for what I couldn't get," said Mabel Smith, 75, a prim woman with a dignified air. In their Burwood Avenue home, the Smiths built a family library and supervised homework. And, Mabel Smith said, "I did not send my five children to church. I took them."

Smitty: `Racism wasn't even a word people used then.'

Broyles: `It was just something you knew was there, like an imaginary line."

When Troop No. 222 showed up at Woodland Trails for campouts, rangers assigned it to the rear of the park. No latrines. No water, the two recalled.

When Broyles was in the third grade at Jackson Elementary School, he watched as whites began abandoning the Chicamauga Avenue neighborhood for Kettering.

"I was losing so many friends, the Rogers brothers who spent the night over my house," Broyles said. "It was a funny feeling."

But he always had his friend Smitty - whether they were learning to shine shoes at the Den Mother's house, or out in the streets fighting.

In the late 1960s, most of Dayton's 74,000 or so blacks called West Dayton home. Though some were teachers, lawyers and doctors, the majority worked menial, low-paying jobs

In Broyles' senior year, he made the high school honor roll for the first time. "It was a matter of applying myself," he said. He visited a predominantly white Christian college in Michigan, but decided against it. "It was just too far away and unfamiliar." By the time Broyles graduated Roosevelt High School in 1966, it had gone from 40 percent white to nearly all black. Still teachers pushed him to work harder as if they were expecting some great change.

At all-black Dunbar High, Smitty's teachers also acted as if times were about to change. Some even talked in the classroom about King's movement. And local blacks were protesting more, like the 1963 Congress of Racial Equality picket at Rike's downtown.

By eleventh grade, Smitty had a chance to enroll in one of the first

government-funded summer college-prep programs for minority groups. However,

the idea of college didn't quite catch on for either Smitty or Broyles.

By eleventh grade, Smitty had a chance to enroll in one of the first

government-funded summer college-prep programs for minority groups. However,

the idea of college didn't quite catch on for either Smitty or Broyles.The working world

So after graduation in 1966, the two went to work - Broyles at GM's Delphi Chassis Kettering suspensions parts plant as janitor. Smitty was one of the first black employees at Ahart Engineers. That stressful distinction marked his professional life and that of thousands of blacks, from the late 1960s to the 1980s, who took positions never before available.Enforcement of equal employment laws, passed as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, increased with time. Private companies began to hire more blacks.

But subtle encounters led Smitty to believe that "they didn't see me as a skilled designer. They saw me as a black first."

At GM Kettering, Broyles moved from janitor to the production line, assembling shock absorbers. Three dollars-plus an hour was good money, enough to care for Josephine, the high-school sweetheart he married, and their newborn son.

At GM Inland, which is now GM's Delphi Chassis plant on Home Avenue, blacks were finally getting a fair crack at skilled jobs. Some workers formed "Second Family" to recruit other blacks for skilled trades. James Brown was one of the founders.

Because of the Second Family effort, Smitty took and passed the GM apprentice test. He became a sheetmetal worker at the Home Avenue plant, and his ambition kept him at GM well beyond a decade. But his outspokenness on race matters antagonized some whites, Brown said.

Some blacks in lesser positions saw Smitty as the "Negro who made it." Others labeled him a "Tom" who bowed down to whites to move up the ranks.

Friends still friends

But there was none of that between Smitty and Broyles.It didn't matter that Broyles was at a standstill after moving from janitor to the production line. Come Friday night, they were "hanging" on West Third, wearing bell-bottoms and dancing to Dayton funk.

Broyles: "We were friends. What we made or what kind of car we drove didn't matter. We could be ourselves with each other."

On the assembly line, Broyles was discovering something about himself. Repetitive factory work did not suit him. He was a people person. In 1976, after 10 years at GM, he left.

"I left mad. I walked out and didn't go back and didn't know what I was going to do. My wife was livid. My parents called me a fool." All his life, Broyles' father, the jailhouse janitor, had just wanted a good factory job.

"In hindsight, I should've stayed, if only for the benefits. I'd be retired now too," Broyles laughed then fell silent.

Smitty was scratching to get out of the factory, too.

"I wanted to get into business. One of my mentors told me to join the Jaycees,"Smitty said. "I got a chance to apply some skills like budget planning and I felt a lot better about myself."

By the late 1970s, King's dream of equal opportunity was more real than it had ever been. Black mayors ran major cities. Dayton's first black Mayor James H. McGee was in his second full term. At age 34, Smitty got a notion to enroll in Central State University. He studied economics and graduated summa cum laude.

After leaving GM, Broyles fell into a funk. Smitty coaxed him out. "GM may not jibe with your soul," he told his friend. "But there's opportunity out there if you take it."

Broyles rose out of his slump. He got a chauffeur's license and a job driving a delivery truck for Dayton Mattress Co. It was 1976. He would remain there nearly 20 years.

"I wasn't making factory wages, but I was comfortable," he said.

Paths diverge

From there, their paths diverged. On a summer day in 1984, Smitty left for New Haven, Conn., and Yale University. He was fired up, cocky, out there in the daring winds, just as he had been in their Cub Scout days. Broyles would miss his buddy. "I always knew that Smitty would do good," he said. Smitty promised to return. Broyles believed him, even though he saw all

around him black people moving away from old neighborhoods and friends.

Smitty promised to return. Broyles believed him, even though he saw all

around him black people moving away from old neighborhoods and friends.Smitty had gotten a scholarship and a fellowship to Yale after attending a special summer program for minority group members at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh, and another at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Business. "Yeah, the programs were especially for blacks, but you had to prove yourself with a 3.0. It was a meritocracy," he said.

He won praises from professors like Ed Klein: "He was a hard worker and a thinker in a challenging atmosphere."

Back in Dayton, Broyles relished the $50 tips he got delivering mattresses in the south suburbs. And he noticed a few blacks moving in along Alex- Bell Road.

Smitty kept his promise. In 1986, armed with an Ivy League master's degree, he returned to Dayton. He got involved in local politics as chairman of Mayor Richard Clay Dixon's inaugural committee. He found himself in the headlines when the city's second black mayor was accused of urging the budget office to hire Smitty. There never was a job offer.

That left a bitter taste that sent Smitty to Cummins Engine Co. in Memphis in 1987. He moved to a predominantly white suburb and sent his two sons to the local schools. Success felt good. The money was great. But Smitty struggled for comfort.

"People saw me as the Yale-educated successful black man, but Steve and the guys were with me when I was getting my butt kicked at GM. They wanted to be with me not because of a Benz or a Jag, but because of who I am."

He returned to Dayton in the fall of 1989 and bought a house near his old neighborhood. He joined The Ohio Company as a broker in 1990. Broyles marveled at Smitty's ride to the top.

Smitty had the car. The vacations in Jamaica. And whites' respect.

Then Broyles found himself hitting the bottom.

One day in 1995, he returned midday from a delivery to find a padlock on the door of the Dayton Mattress Co.

"I was low. I couldn't get no lower. To have spent more than 15 years and no benefits, no retirement and no place to go all of a sudden."

He looked around at other buddies he had grown up with and they were doing well, nice homes, security.

Smitty didn't let him off easy: "I told Steve, there's opportunity out here if you want to fight for it."

"It's my fault where I am. I know that I'm the biggest procrastinator in the world," Broyles said. But the change, the opportunities, came so fast, in a blur, faster than he could've imagined that spring day in 1968. Or maybe he never really believed that they were meant for him.

Broyles lived with his mother for a while. And Smitty helped him get back on his feet. Broyles started looking ahead. He found work. He took some courses at Central State West toward a psychology degree he began earlier. He wanted to set a better example for his son.

Motivation a concern

Keith Broyles, 23, sketched cartoons quietly in his living room where he lives with his divorced parents. Quiet and shy with a goatee, Keith chooses his words carefully.Though he dropped out of Colonel White High School and later earned a GED, he left confident about his artistic ability but unsure what to do with it. "College, I'm not sure it's the way for me to go," he said.

He leaves the house to go to his part-time job at the Subway fast-food shop on Salem Avenue. His brother, Kevin, 30, is married with four children and works for a lumber company.

Both attended integrated schools. And Broyles is proud of Keith's ability to relate to whites.

Keith "is smarter than me, got knowledge and skills that I didn't have that can carry him through," Broyles said. "He won't need affirmative action because of race. He gets along with white people better than I do."

But Broyles wishes that his younger son was more motivated. "I know that in some ways it may be my fault because I put things off."

One evening, Waymond Smith, 18, pulled the 1986 Volvo into the driveway on Lakeside Drive. His older brother, Irvin Curtis, 23, a Central State University student, was waiting to take off in the car they share.

Waymond is a savvy kid. He has attended predominantly white schools in Connecticut and Memphis, and integrated schools, public and private, in Dayton. Now, as a senior, he opted to attend Dunbar High School. "I wanted to be in an all-black school."

Like his father, he knows the "street" and Wall Street. And like his dad, he's got the guts to speak his mind. But his assertiveness is too tempered for Smitty who doesn't like the B's and C's on Waymond's report card.

Different challenges

Smitty worries that the spoils from the civil rights bounty that he has cashed in on may have rendered his boys spoiled and lazy. They don't seem to work as hard as he did.After all, raw racism and opportunity lockout are strangers to Waymond.

Father: "Absent the same challenges, they don't have the resiliency or aggression to be successful. Relative to competitiveness, they're behind the learning curve."

Son: "I don't think it's all about being tough. It's about being smart and making the right decisions."

Smitty worries that rap music is programming his son for failure. What happened to songs that motivated the movement like Moving on Up ?

One rainy afternoon at his office on Main Street, Smitty looked through the

board room window and nodded his head as a youngish man in worn clothes

hurried down Main Street toting a soiled bag.

One rainy afternoon at his office on Main Street, Smitty looked through the

board room window and nodded his head as a youngish man in worn clothes

hurried down Main Street toting a soiled bag.Are blacks better off than they were 30 years ago? Can his boys make it on their own without set-asides, quotas, preferences or special programs like the ones that helped send him to Yale?

"Yeah, we can make it," he said, his gravely voice cocky. "As long as you have human beings, you'll have biases. So fairness, to me, is giving me a chance to come in and show what I can do."

Across town at Cornell Heights Elementary School, Broyles, in sanitary gloves and T-shirt, sweeps a pile of notebook paper, pencil shavings and broken crayons.

"Do I believe in the American dream? Yeah. ... When's the last time you heard of someone trying to defect from the United States? Everybody's trying to get here. But it's not a `gimme.' You've got to work."

Sidebars to Part 1:

THE DAYTON DREAM

Local baby boomers focused on the music and culture of the black experience

FEDERAL LEGISLATION AFFECTING BLACKSPart 2: Privilege and problems in the suburbs:

Rising incomes and fair housing laws have opened Miami Valley suburbs to growing numbers of black people. Yet many blacks have discovered that the advantages of suburbia are offset by new obstacles.