By Jeff Nesmith and Russell Carollo DAYTON DAILY NEWS EL PASO, Texas - Until the morning Donald McKinley's wife found him face-down in their back yard, he might have been treated for the clogged arteries that finally failed him. |

Published: Tuesday, October 7, 1997

|

Kayla Reardon does schoolwork on the living room floor. Kayla

has cerebral palsy, which her parents say results from a failure by

Wright-Patterson Medical Center doctors to properly treat her mother

Kimberly (rear) for asthma during pregnancy. (see sidebar).

Kayla Reardon does schoolwork on the living room floor. Kayla

has cerebral palsy, which her parents say results from a failure by

Wright-Patterson Medical Center doctors to properly treat her mother

Kimberly (rear) for asthma during pregnancy. (see sidebar).SKIP PETERSON / DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

McKinley, 67, saw Dr. Andrew Curtis Faire at the William Beaumont Army Medical Center here seven times in the months before he died. Dr. Faire, suspecting sore muscles were causing the abrupt pains in McKinley's arms and shoulders, prescribed an anti-inflammatory drug.

Three weeks after the last visit, McKinley was dead. An autopsy would later show his arteries were 95 percent clogged in places.

Had the coronary artery disease been diagnosed, a Houston cardiologist told government lawyers, McKinley "probably would have had a bypass and ... probably would still be alive today."

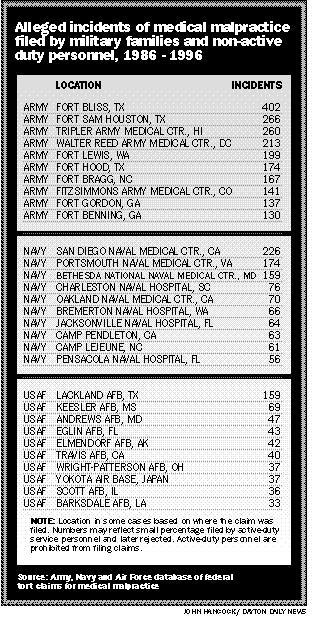

To settle a medical malpractice claim, the government agreed a few months ago to pay Pauline McKinley approximately $300,000. Her claim represents one of 402 cases of alleged medical malpractice at Beaumont from 1986 to 1996.

Those cases push Beaumont to a grim distinction: the hospital with more malpractice claims than any other military health facility in America. A Dayton Daily News examination found William Beaumont not only was targeted for more malpractice claims than any other hospital, just four other hospitals had even half as many claims as Beaumont did over the 10 years. Beaumont, a 306-bed hospital at Fort Bliss on the outskirts of El Paso, was targeted for more claims than the combined total for the Bethesda Naval Medical Center and the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, which together have three times as many beds.

Why Beaumont would have so many more claims than other hospitals is not clear. In fact, documents filed with court cases and interviews with lawyers and military health care experts show the problems at Beaumont occur to some degree in all 115 hospitals and medical centers and 471 clinics that make up the Military Health Services System.

The overall problems appear to stem from a variety of sources, including:

* Downsizing: The military reduced the number of physicians by 8 percent between 1991 and 1995 and is expected to force an additional 8 percent reduction by 2000. While the entire military has been downsized, many hospitals face increasing patient loads. That's because retirees like McKinley are eligible for health care through the military. And as more members of the all-volunteer Army reach the 20-year retirement eligibility, the number of retirees and their families is expected to grow through the end of the century. In one internal Department of Defense survey, 13 percent of the patients complained of having to wait an hour or more to see a doctor.

* ``Take-a-number'' patient management: Understaffing, poor records management and the constant shuffling of personnel in military hospitals and clinics undermines continuity of care and forces many beneficiaries to see whatever doctor is available. Many patients are forced to carry their medical records with them every time they see a doctor.

* A fortress-like bureaucracy: The secrecy found in all medical centers is compounded in the military by policies and command structures that appear to place greater value on the doctor's protection than on the patient's right to know. Patients may never find out what happened to them, and even when they do they are forbidden by law to name the doctor as a defendant in a malpractice lawsuit.

* Changing and often contradictory priorities: Primarily responsible for training young doctors to go to war, military hospitals are serving needs far removed from the battlefield. Defense Department records show the top two reasons for military hospitalizations in 1992 were the delivery of babies and the care of newborn infants.

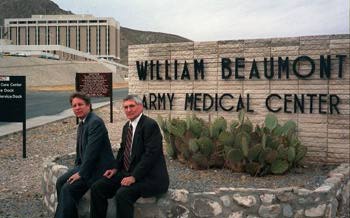

Attorneys Walter Boyaki (left) and retired Army Lt. Col. John

Caldwell sit in front of the Beaumont Army Medical Center in El

Paso, Texas. Boyaki has collected more than $20 million in judgments

against the military. Caldwell, sent to El Paso as a special

assistant U.S. attorney to defend against claims by Boyaki and

others, now works in Boyaki's law firm.

Attorneys Walter Boyaki (left) and retired Army Lt. Col. John

Caldwell sit in front of the Beaumont Army Medical Center in El

Paso, Texas. Boyaki has collected more than $20 million in judgments

against the military. Caldwell, sent to El Paso as a special

assistant U.S. attorney to defend against claims by Boyaki and

others, now works in Boyaki's law firm.JEFF NESMITH / DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

``It's an institutional problem that I don't think they can correct,'' he said. ``The patients are by statute entitled to free medical care, so they are treated like welfare patients. Then, you overlay on that a military system that protects its own.''

Lt. Gen. (Dr.) Ronald R. Blanck, surgeon general of the Army, said the hospitals under his command see an average of 47,000 patients and perform 350 operations every day. `Indeed, sometimes there are bad outcomes, but (on the whole), it's both unfair and in fact dishonest to use some of those outcomes, I think, to color the system, to make some generalizations about the whole system,'' Blanck said.

The Army does not identify the doctors involved in alleged malpractice cases. However, records show Faire was the physician in at least five malpractice claims at Beaumont since 1983. Two of the claims were dismissed by federal judges. The other three charged that medical malpractice preceded the deaths of three of Faire's patients. The Army paid negotiated settlements in all three but denied responsibility.

Three malpractice settlements involving patients who died could wreck the career of a physician in private practice, setting off reviews by ``peer committees'' and malpractice insurance underwriters and causing high premiums. But Faire doesn't have to worry about insurance premiums because he doesn't need insurance. All claims are paid by the government. And he is immune from lawsuits because, by law, military doctors cannot be named as defendants in damage claims.

Faire declined to answer questions. Acquaintances described him as a dedicated and meticulous physician who often is overwhelmed by conditions that require him to see too many patients in too little time.

In court depositions and written statements to his superiors at Beaumont, he has complained that administrators require him to see so many patients that he often has to stay in his office after hours to catch up on paperwork and "personally hand-punch the proper holes" in laboratory reports so that they can be attached to other records.

In a notation on one lab report in April 1984, Faire admitted having failed to recognize blood test results that would have alerted him to the fact that Carol Barnes had leukemia.

The test showed that she had a white blood cell count of 98,000.

Adjacent to this figure, the laboratory report noted that a healthy count would have been somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000. Doctors who treat blood diseases say a white cell count of 98,000 is highly suggestive of leukemia.

``Missed the w.b.c of 98,'' he wrote at the bottom of a subsequent laboratory report. ``Thinking 9.8.''

In less than a year after the first visit Barnes was dead.

Barnes had a deadly form of leukemia. Yet, prompt chemotherapy and bone marrow transplants could have afforded her a lengthy remission, said Dr. Ronald S. Walters, a Houston blood specialist who treated her in the final stages of her illness. Barnes, the wife of an active-duty warrant officer and physician assistant at Beaumont, filed a medical malpractice claim against the hospital. The Army settled the claim after her death.

Leon Taylor was a retired Army lieutenant colonel who operated a small garage door business in El Paso and regularly availed himself of his right to medical care at Beaumont. On June 29, 1993, he was gravely ill, but no one knew it.

He visited Faire that day for a routine physical. After office hours, Faire typed in the vital signs: blood pressure, 109 over 61, pulse rate of 69, weight, 198 pounds. He had ordered a chest X-ray and noted: ``CXR; compared to March-1991.

No active dz. (disease).''

But an outside radiologist who examined the same X-ray said it clearly showed a tumor in Taylor's right lung. Any record that it was examined by radiologists at Beaumont was either lost or never existed.

The tumor might have been treatable; but a year later, when it appeared on a second X-ray, it was diagnosed as incurable.

Like Carol Barnes and Donald McKinley, Leon Taylor died. The Army paid a negotiated settlement to his widow.

``Dr. Faire is a very nice man, but in my opinion if he were in a civilian hospital, he would have had his credentials lifted or severely restricted years ago,'' Boyaki said. ``At William Beaumont, the guy could be passing out cyanide and nothing would ever happen to him.''

Beaumont spokesman Ron Joy insisted that the hospital's patients are well cared for.

``William Beaumont Army Medical Center provides the same high quality care that our other medical centers do,'' he said.

A litigious atmosphere at Beaumont

One reason for the large number of cases at Beaumont, Boyaki and others say, may be the accumulating effect of the cases themselves. Military personnel and retirees and their dependents throughout the armed services are often unwilling to sue the military - and in some cases are unaware that they can sue. But that appears to be less true in El Paso, which has been exposed to numerous high-profile claims against Beaumont.

``We don't really know,'' spokesman Joy said when asked what hospital

officials thought accounted for the large number of claims. ``Beds are only

one of the variables that may be relevant to the number of tort claims.

Perhaps it has something to do with the highly litigious atmosphere in the El

Paso area.''

``We don't really know,'' spokesman Joy said when asked what hospital

officials thought accounted for the large number of claims. ``Beds are only

one of the variables that may be relevant to the number of tort claims.

Perhaps it has something to do with the highly litigious atmosphere in the El

Paso area.''

Some of the hospital's most damaging publicity grew out of a seven-month period in the early 1980s involving a Beaumont brain surgeon with a drinking problem.

Dr. E. Neil Gunby, a lieutenant colonel in the Army, admitted he was an alcoholic after a nurse insisted that he be given a blood test. The nurse said Gunby showed up smelling of alcohol and slurring his speech at the bedside of a baby who had a massive skull fracture. The child survived after a second neurosurgeon was called to the hospital.

Between June 1981 and February 1982, two of Gunby's patients, ROTC cadet Reuben Flores Jr. and Army Specialist Larry Carter, died.

Howard Vought, a military retiree living in El Paso, charged in a malpractice claim that he was left brain damaged and blind after surgery by Gunby.

Agustina Gutierrez made a similar claim.

Carter's widow filed a malpractice claim against the hospital, but it was dismissed because the government cannot be sued for any harm done to an active duty member of the military.

The government paid claims filed by Flores' parents and by Vought and Gutierrez.

The extent of Gunby's drinking problem and the failure of the Army to respond to repeated warnings emerged in sworn depositions taken from witnesses in the Gutierrez case.

According to testimony in the case, Flores' father said that he smelled alcohol on Gunby's breath the morning his son underwent surgery. The youth died shortly after the operation.

The hospital commander, Brig. Gen. Chester Ward, who has since retired from the Army, acknowledged in another deposition that he had received several complaints from hospital staff members. In response to one complaint, Ward said, he talked to Gunby and ``smelled his breath.'' He said he took no action because he did not smell alcohol.

Another brain surgeontestified that he had reported Gunby's apparent alcohol problems to several hospital officials and to the office of the Army surgeon general in Washington, but nothing was done.

An officer in the surgeon general's office testified Gunby was working at Walter Reed when his drinking problems first became apparent in 1980. He was subsequently transferred to Beaumont, where he was made chief brain surgeon.

Another physician said he was pressured to alter his testimony criticizing Gunby's treatment of Gutierrez and threatened with court-martial on an unrelated matter. Other witnesses testified that hospital records in some of the cases could not be found.

Gunby acknowledged that he was an alcoholic but denied harming any patient.

It was Maj. Donna Zepecki, the nurse, who finally brought the matter to a head. Zepecki testified that she had notified several of her superior officers, including Ward, that she had received reports of Gunby's drinking. She said nothing was done.

Finally, following the episode involving the baby with the skull fracture, Zepecki insisted that Gunby be given a blood alcohol test, which she said he failed.

``The day it happened, it seemed as though the general contention was going to be, well, let's just send him home and leave it at that,'' she testififed. ``And I just kind of raised all sorts of hell. And I said, `This is not a new problem. We cannot treat this as though, you know, just push it under the rug.' ''

After treatment in the Beaumont alcoholic rehabilitation facility, Gunby was promoted to full colonel and transferred to Madigan Army Medical Center at Fort Lewis, Wash. Within months, a patient at that hospital charged that he had been permanently harmed while being operated on by Gunby. The Army paid a cash settlement.

Gunby was subsequently transferred to Walter Reed, where he retired three years ago, according to Army records. He did not respond to messages left on his telephone answering machine.

Two kinds of doctors in the military

When Gunby was transferred to Walter Reed, he went to one of the military's finest hospitals. Walter Reed and Bethesda are the crown jewels of the military's health care system. But even there, patients can encounter examples of bad care.

Bryce Campbell says that doctors at the Army's Walter Reed Medical Center tore open an artery at the base of his brain. Campbell, shown with wife Marla, cannot sue the military because he is on active duty. A. SCOTT MACDONALD / FOR THE DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

But Young's surgery did not go well. Young and his aides declined to talk about it, but Rep. Bill Murtha, D-Pa., raised questions about Young's care at a hearing of the subcommittee in March.

``This past summer, we had a bad experience from one of the most prominent members of Congress, who went out there to Bethesda and his life was actually threatened by the care that he got,'' Murtha said.

``I am concerned about cutting nurses at Walter Reed, at cutting care,'' he told the Daily News . ``We have cut the care to the bone at Bethesda, and I wonder if we really are getting good care now.''

Navy Lt. Bryce Campbell may never know what happened to him last year at Walter Reed. Radiologists at the Washington, D.C., Army hospital deny tearing open an artery at the base of his brain, though an internationally known neuro-radiologist says they did.

After discovering an abnormal snarl of veins and arteries in Campbell's brain, the Walter Reed radiologists tried to infuse the malformation with a dye that shows up on X-rays. To do this, they inserted a thin catheter carrying the dye into an artery in his groin and tried to thread it up past his heart and into his brain.

His wife, Marla, said that when he came out of the operating room, ``he was whimpering and moaning in pain and saying to me that he was seeing lightning bolts and streaks. I thought he was having a stroke.''

Later, the Army transferred Campbell to George Washington University Hospital across town where Dr. William O. Bank attempted to use another catheter to close off one of the arteries and relieve pressure on a vein.

``They told me Dr. Bank was the best of the best,'' Marla Campbell said. In fact, patients come to George Washington from all over the world to be treated by him.

``When we got to George Washington, Dr. Bank started to explain to Bryce and me about `the problem at Walter Reed,''' Marla Campbell recalled. ``We looked at each other and said, `The problem?'''

It fell to Bank to inform them that during the procedure at Walter Reed an artery was torn open. It subsequently healed in a way that left it 95 percent closed.

Bank was unable to negotiate a micro-catheter into the problem area in Campbell's brain and therefore could not treat him. He is plagued by memory problems, mood swings and sleep disorders, Marla Campbell says.

Meanwhile, unaware of what happened at Walter Reed, the Navy began to make arrangements to dismiss Campbell from the service because he failed to make a mandatory promotion to lieutenant commander.

``I was frantic. We were suddenly looking at not having a paycheck and all these medical bills that we would have to pick up,'' Marla Campbell said. But when she appealed for the Navy to keep him until his medical problems were solved, the personnel officer asked, ``What medical problems?'' She said she later discovered that medical records that should have been kept at Bethesdawere missing.

Because of the medical problem, the Navy has postponed plans to dismiss him from the service. As an active duty member of the military, he cannot sue the Army over the incident at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

Campbell, a native of El Paso, wrote to Sen. Phil Gramm, D-Texas, asking for assistance in finding out what had happened. Gramm forwarded his letter to the Pentagon.

In response to Gramm's inquiries, Walter Reed radiologists denied the artery in Campbell's brain had been torn.

Bank said records in the case suggest to him that this was because Walter Reed physicians were not aware that they had dissected Campbell's left interior carotid artery, the vessel that provides blood to much of the brain.

The catheter tubes, thinner than a toothpick, have a slight bend at the leading end. Whenever a radiologist comes to a place where he needs to change directions as he makes his way through the patient's arteries, he twists the tube slightly in order to aim the bend in the right direction.

``You use the bend to guide it,'' Bank explained. ``You have to use a lot of finesse. When people get into trouble, it's usually because they rely on force, rather than finesse.''

Bank, himself a former Navy flight surgeon, said he could not comment on the care Campbell got at Walter Reed because he did not know precisely what happened.

But, he added, ``There are two kinds of doctors in the military. They're either fabulous, wonderful doctors, or they're spectacularly incompetent.''

Sidebars to Part 3:

WRIGHT-PATTERSONPart 4:

DOCTORS CHANGE, RECORDS GO ASTRAY

* Continuity of care is often a luxury in military hospitals, and lack of it can be fatal.

Special Licenses For Some Doctors

Despite a mandate that doctors in the military hold state medical licenses, at least 77 practiced without meeting the minimum licensing requirement.