AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

HE TURNED FRUSTRATION INTO MOTIVATION

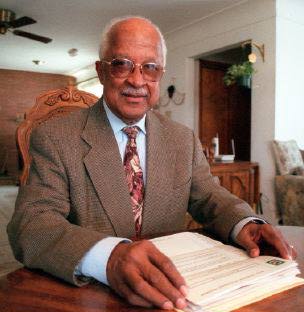

A Dayton man headed WPAFB's equal employment opportunity office.

Published: Tuesday, April 7, 1998

By James Cummings DAYTON DAILY NEWS

John E. Moore Sr. returned to Dayton in 1946 after World War II, and he

landed a slot in a carpentry apprenticeship program.

John E. Moore Sr. returned to Dayton in 1946 after World War II, and he

landed a slot in a carpentry apprenticeship program.But, "Instead of learning carpentry, they had me digging ditches," Moore said. "That made no sense at all to me."

For Moore it was just one more indignity, one more frustration, one more bit of abuse suffered because he happened to be a black man in the 1940s.

But instead of lashing out, Moore turned his anger to motivation. He educated himself and eventually headed Wright-Patterson Air Force Base's equal employment opportunity office in the 1960s. He helped design and enforce policies that are models for programs continuing today.

Moore, who retired in 1979, is a forerunner to thousands of black baby boomers employed by Wright-Pat, the largest government employer in the Miami Valley. His EEO experience provides an interesting glimpse into the beginning of affirmative action programs.

"When I got out of the military I was a very angry young man," Moore said. "That's one of the reasons I felt so strongly about working in equal employment opportunity. It was an exciting thing to have an opportunity to be a change agent."

John Moore worked for the EEO at Wright-Pat. He helped design and enforce policies that are models for programs continuing today. BILL REINKE/DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

And Moore also promoted the policy of going to predominantly black colleges to recruit for professional positions, a practice that continued when the base was actively expanding its workforce, said current base personnel head Michael O'Hara.

Pamela Sotherland-Clark, a Wright-Pat employee and the current head of the EEO council, said, "We even have an award named for John. He was a real pioneer." Moore graduated from Wilbur Wright High School in 1941 with good grades and a willingness to work. But he couldn't find a private sector job because of his race.

"When I came along, we had to prepare ourselves even though the opportunities weren't always there."

"In '41, Dayton was a manufacturing town, and you just got screened out if you were black," he said. "All the factories and small companies if they were looking for black employees they were looking for people to push brooms, and not many of them."

The federal government, though, was under executive order to integrate, and local federal institutions hired blacks much more readily than private employers.

"The best illustration was the post office," Moore said. "Even before the war, there were a lot of blacks with degrees - preachers, teachers, lawyers, doctors - working for the post office. It was one of the few places that would hire them."

Moore took a clerical job at Wright-Pat in 1941 when he couldn't find anything else. Later he went into the Army for 30 months, then reclaimed his Wright-Pat job.

Using GI Bill benefits, Moore enrolled in night school at the University of Dayton and spent nine years earning a business degree. He later went to graduate school at Ohio State University.

And he worked his way up at the base, first in military intelligence and later in personnel. In 1965, when new federal orders strengthening equal employment opportunity requirements went into effect, Moore was named to head Wright-Pat's program.

"We spent an awful lot of time talking and jawboning," he said. "We had to change some attitudes and behaviors as well as inject some fairness into the way complaints were handled." Moore said military and civilian personnel at the top of the chain of command were solidly committed to hiring and promoting blacks and treating them fairly on the job.

But middle managers and line supervisors were more of a problem.

"A lot of supervisors just didn't believe they had any biases or didn't think they needed to change," Moore said. "We spent a lot of time on education and training, particularly for supervisors."

Moore said improving the complaint handling process was critical. Before the late 1960s, black workers who felt they were mistreated or discriminated against had few effective grievance procedures.

"We established informal and formal complaint procedures .... The goal was making sure everybody felt the system was fair no matter who made the complaint."