UNEMPLOYMENT

NO JOB, FEW PROSPECTS

* Unemployment rates for blacks here double that of whites.

Published: Tuesday, April 7, 1998

By Marcus Franklin DAYTON DAILY NEWS

At 20, William Smith Jr. must confront problems common to men twice his age.

Smith, who has a wife of eight months and a bright-eyed 3-month-old son, has no job to support his family or relevant skills to get one.

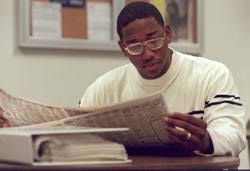

William Smith Jr. flips through ads while sitting in a job bank. SKIP PETERSON/DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

"I look at them and I think, `I gotta get a job, I gotta get a job,''' Smith said as he sat with his family in a job bank flipping through ads on his 20th birthday last month. "That runs through my mind every day," he added as he turned his attention back to the ads.

Chronic unemployment among blacks in the Dayton-Springfield area is hardly a new phenomenon.

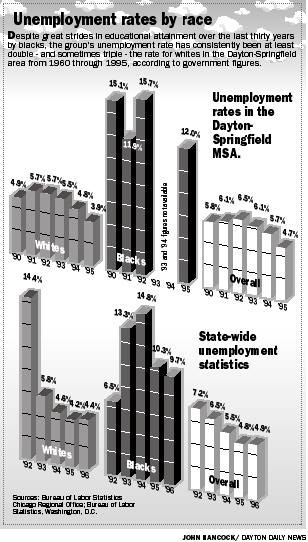

Since the 1960s, black unemployment rates have been consistently at least double and sometimes triple the rate for whites in the area, according to U.S. Census and Bureau of Labor Statistics figures.

This bleak trend flies in the face of great strides in higher education by blacks and of current near-record low overall unemployment levels. In 1995, for example, the white unemployment rate in the Dayton-Springfield area was 3.9 percent, according to the BLS Chicago Regional Office. For blacks, the rate was 12 percent that year.

While experts say the Dayton-area economy is tight, gone are the days of abundant high-paying, entry-level blue-collar manufacturing jobs, once financial stepping stones to the middle class for many blacks.

Those jobs have been replaced by lower-paying, high-tech and service-related posts, said Robert Brown, a manager at the Ohio Bureau of Employment Services, which co-manages the Job Bank in The Job Center at 1111 Edwin C. Moses Blvd.

"The parent (of people currently in the workforce) might have had the job at General Motors at $15 an hour but (companies) are not hiring at that wage anymore," he said.

The reason for the constantly disproportionate unemployment rate for blacks is complex and multi-pronged, structural and behavioral, experts said.

"You start with (structural) racism," said Richard Stock, senior research associate at the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Dayton. "It's not an opinion; it's been documented by the U.S. government: Employment discrimination still occurs."

Stock pointed to the proverbial example of two job applicants - one white, the other black - with identical qualifications. Both are the same age and they apply for the same job.

"Four out of five of the interviews, discrimination won't happen," Stock explained. "But the fifth person being treated differently (because he or she is black) matters at the margin. It's not typical but it's persistent and it matters at the margin."

Stock, who added that the legacy of unequal education in America is also a

factor, said the unemployment rate among blacks is actually much worse than

the numbers illustrate.

Stock, who added that the legacy of unequal education in America is also a

factor, said the unemployment rate among blacks is actually much worse than

the numbers illustrate.

The unemployment rate, he said, doesn't capture the "labor force participation rates" which include everyone who is available for work, including those "who get tired of going out and having doors slammed in their faces."

"So those people who have given up, they don't get counted as part of the unemployment rate."

Brown, however, insisted that structural racism is no longer as great a barrier to employment as other obstacles such as a lack of high-tech job skills, child care and transportation from the city to outlying areas where many of the new jobs are appearing.

In March, a UD and Wright State University study counted 48,000 unfilled jobs in the Miami Valley, roughly a quarter of them paying at least $30,000. Most of the job shortages, though, were in low-wage categories, the study noted.

"The jobs leaving the inner city aren't being replaced," Brown said. "We as minorities have to prepare ourselves to go where those jobs are. A lot of times we call people in the inner-city with jobs and they tell us, `It's too far.'

"There's a lot of jobs out here but people aren't prepared."

Finding employees with "a good work ethic is also a part of the problem," said Brown, adding that the problem isn't exclusive to blacks.

"People don't have a sense of getting up and getting to that job, no matter what, every day. Attendance is a major problem as well as having a good attitude and good social skills."

The grim unemployment numbers don't need to be told to Carmen Norvell of Dayton. Norvell, 36, is a breathing example of them.

Earlier this year, the former telemarketer and customer service representative was fired because she lacked "computer skills," she said. She'd worked for a Dayton company for five years.

"I was disappointed," said Norvell, who draws unemployment while she looks for work and attends a computer training class.

Last February, Smith quit his 5-month-old, $8-an-hour factory job because of "severe racism" and rumors that the company planned to lay off, with new hires the first to go.

"At the time, my job security didn't seem too stable, too firm. I thought it'd be best for me to get out ahead of time," he said.

For sure, Smith regrets his decision. Finding another job that pays enough to take care of his family has been difficult, he said.

"I know that (quitting) wasn't too smart, but I wasn't really thinking. I was upset."

Neither he nor his wife Shawanda, 19, has much education beyond their high school diplomas. But they're optimistic.

"I'm praying something comes through. You can't do much, without a job, to support your wife and child."