|

THE SUBURBS BECKON Moving up signals accomplishment |

`Good morning,' said the woman, who was out walking her poodle. `Do you charge by the hour? I have been looking at all the things you have done with this yard, and I'm so impressed. I need somebody to help me.' Ivory, who owns the Latch-On Academy day care centers, was amused.

Tonya Ivory and her family in front of their Washington Twp. home. Behind Tonya is her husband, Richard, her daughter, Ryan, and her son, Jourdan. DDN photo by Skip Peterson. |

The woman was mortified at her own presumption, but in a way, it was forgivable: Before the 40-year-old Ivory and her family arrived, blacks had never lived in the affluent neighborhood tucked south of Whipp Road.

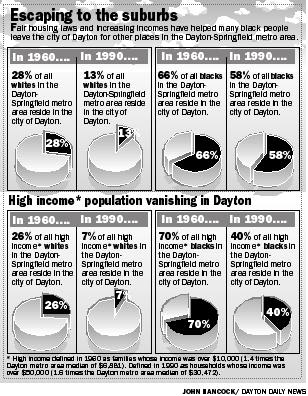

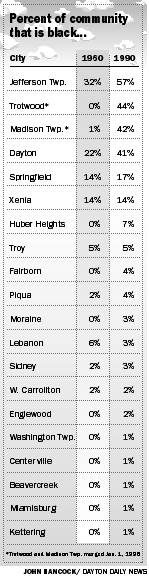

Three decades after the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed residential discrimination, the suburbs beckon as a land of opportunity for blacks in the Dayton-Springfield area. The number of blacks living outside the core cities of Dayton and Springfield has more than doubled over 30 years, to 40,000 from 16,000.

Suburbia offers the same opportunities that entice whites from the city: the hope for better schools, safer streets, firmer home values and a break from crime.

But home prices put the suburbs beyond the reach of many area blacks. For example, in Ivory's neighborhood in Washington Twp., the median selling price for a single family home last year was $146,250. The median price in the entire valley was $96,500. And mortgages continue to remain elusive for many blacks. In 1996, the latest year for which data are available, blacks in the Dayton-Springfield area saw their mortgage applications rejected or withdrawn at twice the rate of whites - 40 percent to 20 percent.

It's clear King's dream of opportunity hasn't unlocked the doors to the middle class for great numbers of local blacks. Only a quarter of the region's black households made more than $35,000 in 1990. But even those who can afford the move to the suburbs encounter a dual life of privilege and problems. Some confront subtle slights and outright harassment. Others hear the taunts of fellow blacks who consider them sell-outs. And all struggle to keep connections to their culture and heritage alive.

The perfect escape

In the early 1970s, Dayton probation officer Grafton Payne II had grown weary of the cons who continually dropped by his Huron Avenue home to seek sympathy or hurl threats. He wanted a way out of town, and Madison Twp. seemed like the perfect escape.The schools were good. The houses were affordable. The traffic was sparse.

Heather Washington, 10, is one of only two black students in her fourth-grade class at Centerville's Normandy Elementary School. DDN photo by Skip Peterson |

`I had no particular interest in other areas,' he said.

Plenty of others shared his opinion. Starting in the late 1960s, blacks flocked to Trotwood and Madison Twp., an area contiguous to established black communities in West Dayton and Jefferson Twp. By 1990, the city and township were almost half-black.

Black populations rose in other areas as well as the Fair Housing Act of 1968 slowly opened new markets.

A powerful influx went to Fairborn and Huber Heights, cities that lie next to one of the region's largest employers of blacks: Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. In 1960, the two localities had a total of seven black residents. By 1990, they had nearly 4,000.

Some black professionals who landed jobs at Central State, Wilberforce or Wright State universities chose Beavercreek, an upscale community with top-notch schools.

Others settled in southern suburbs that were close to their jobs at places such as Lexis/Nexis, NCR or General Motors.

But as blacks moved to areas where few of them had ever lived, they found a

world bereft of familiar comforts: black churches, businesses, and social

clubs. If newcomers wanted the attributes of a vibrant black community, they

had to create them.

But as blacks moved to areas where few of them had ever lived, they found a

world bereft of familiar comforts: black churches, businesses, and social

clubs. If newcomers wanted the attributes of a vibrant black community, they

had to create them.Two years ago, Palmer G. Jason began a small Bible study group in his Miamisburg home. It grew gradually to 30 participants.

Today, Jason, 36, is pastor of Jubilee Community Church, which holds services in an elegant house on Centerville's West Franklin Street. Most of the church members are black and live in Dayton's southern suburbs. As far as Jason knows, it is the only majority-black church south of the city.

Jubilee has become an alternative for some blacks who feel self conscious about attending services at predominantly white churches, Jason said.

`There are several families here that are perhaps feeling ... that they can't be free to be themselves when they go to worship services,' he said. `Or (they are) not wanting to constantly be in the position where you're in a glass bowl, or a fish bowl, being looked at.'

Severing connections

Dino Ross and his wife Teria moved to Vandalia three years ago, yet every week they return to his mother's house in Dayton for Sunday dinner.There, over pot roast or lasagna, they relax and renew connections that have grown looser since their move to a new four-bedroom house in Woodland Meadows, a tiny subdivision off Helke Road.

They chose the area because it is in the Media One cable system, where Dino works as a dispatcher, and because of its solid property values, good schools for their daughter, and plentiful trees and sidewalks.

But Dino, 40, said it all came with a price.

`We don't get as many visitors as we did when we were out in the Dayton area,' he said. `Most people have a tendency (to feel) that they have to make a special trip to come see us."

`That's the downfall of moving out into a suburban area.'

Still, he and Teria don't feel isolated, despite being one of only two black families in the subdivision.

They formed an early bond with their white neighbors: Since everyone was building houses, they commiserated about contractor problems, time schedules, and other headaches.

That made them feel more comfortable. It would have been `a lot scarier' to move into an established neighborhood, Ross said.

Thomas Koebernick, an urban sociologist at Wright State University, believes whites in neighborhoods without a strong social fabric don't feel threatened by black newcomers.

And as for harmony among the cul-de-sacs: `(Large) lots probably help. Seriously. If everyone is on five to 10 acres, you don't really have to neighbor.'

The Children's Club

Sherry and Bill Washington live in a blond brick ranch house set among dozens of similar homes along a winding Centerville boulevard. If you're looking for suburbia, this is it. One benefit is the school system, and the Washingtons are pleased with the

education their daughter gets at Centerville's Normandy Elementary. They like

the teachers, the other children, and the fact that the school system annually

posts some of the region's highest test scores.

One benefit is the school system, and the Washingtons are pleased with the

education their daughter gets at Centerville's Normandy Elementary. They like

the teachers, the other children, and the fact that the school system annually

posts some of the region's highest test scores.Yet they're concerned that Heather, 10, is one of only two black students in her fourth-grade class.

Sherry, 36, and Bill, 40, absorbed a sense of culture and heritage growing up in Dayton and Jefferson Twp. But they know they'll have to make an effort if Heather and her sister Hillary, 6, are to have the same experience.

Their solution is the Children's Club.

The group is the brainchild of four black women in the Centerville-Washington Twp. area who worried about their children's cultural seclusion. Spurred by an article in Ebony magazine, they decided six years ago to create an organization to support young blacks.

Today, the club has 30 families in its ranks, and they get together monthly for excursions to book stores and museums, zoos and libraries. They end the year with a Christmas and Kwanzaa celebration at the NCR Country Club.

Co-founder Karen Brown-Fallings, a 44-year-old Washington Twp. resident, said the black population seems to be rising in Dayton's southern suburbs, and census figures back up her observation. Among the localities experiencing the greatest percentage growth in black population between 1960 and 1990, Centerville ranked fourth.

Despite the gains, Brown-Fallings said the black community south of Dayton still needs support.

`That's what spawned the Children's Club, just to have people of color getting together, sharing and networking,' she said. ` ... We wanted just to continue to nurture a sense of culture.'

Although the Washingtons and other families try to keep their children connected to their heritage, they sometimes face accusations of cutting themselves off from other blacks.

Last fall, when Sherry attended a meeting of her book club, another black woman mocked her for living in Centerville.

Blacks who live in predominantly white areas were Uncle Toms, the woman proclaimed, snobs who thought they were too good to live with their own kind.

Washington, who defended Centerville's schools and stable property values, wasn't surprised by the outburst.

`Unfortunately, there's a lot of people who feel that way.'

In truth, the suburbs haven't always been a land of ease for the Washingtons. When they first moved south from Dayton in 1987, police cars tailed Bill when he left work at GM.

Sherry's parents, who still live in Dayton, want the family to move back to the city. But she believes sporadic snubs or feelings of solitude are no reason for the family to leave their new hometown.

`You can go across the lines, and nobody better tell me that I can't,' she said. `People, to me, need to get out of their comfort zones.'

Some experts believe that is happening more often. Ingrid Ellen, a professor at New York University, said white suburbanites are getting used to the idea of neighbors with different skin colors.

`White households have been able to see, `Wow, the neighborhood is OK. A few blacks moved in and the neighborhood didn't go to pot,'' she said.

Dino and Teria Ross in their new house in Woodland Meadows, a tony subdivision off South Dixie Drive. DDN photo by Skip Peterson |

She cautioned, however, that many whites - particularly those with children in public schools - still stay clear of areas with large concentrations of blacks. They appreciate minority neighbors only in `modest doses.'

A peaceful street

Tonya Ivory made it to the suburbs, to a peaceful street and a three-story house filled with roses and art. But she thinks about those left behind. She thinks about her brother.Alvin Johnson Jr. was a basketball prodigy at Patterson Cooperative in the 1970s, and was planning to study at Howard University. But a weakness for heroin wrecked his promising future, and he never escaped Dayton's streets. An overdose killed him at the age of 37.

`My brother was a product and a victim of his environment,' Ivory said. `That was my motivation to move my children to this kind of an environment.'

Sometimes, though, she questions the move. When her son faces trouble at his Catholic school, where he is one of four black children, she wonders if it is because of his race. When her husband gets hassled by a bank clerk who won't cash his check, she feels certain of the cause.

But then, she recalls an afternoon three years ago. She was sitting outside, reading a John Grisham novel, when three black housekeepers walking to the bus stop paused to blow kisses her way.

`We're so proud you're out here!' one shouted.

`I hear that a lot,' Ivory said. `I hear it from family. I hear it from people in my old neighborhood. And it makes me feel good. It makes me feel that the village goes with you wherever you go.'