- Continued from -

REPORTING STANDARDS CHANGE DRASTICALLY

Part of the reason the services don't report all accidents is because they're not required to under Department of Defense guidelines. In 1989, those guidelines were rewritten, making it easier for the services to keep from official statistics the type of accidents routinely counted by the civilian National Transportation Safety Board.

Part of the reason the services don't report all accidents is because they're not required to under Department of Defense guidelines. In 1989, those guidelines were rewritten, making it easier for the services to keep from official statistics the type of accidents routinely counted by the civilian National Transportation Safety Board.Military officials said they rewrote the guidelines to exclude certain types of aviation accidents because they believed Congress wasn't interested in knowing about all accidents.

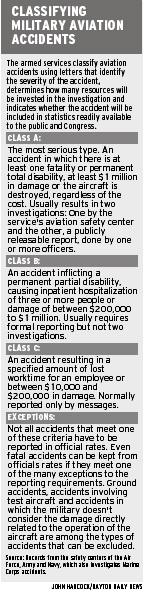

The new guidelines increased the cost threshold for a Class A incident from $500,000 to $1 million and increased from $100,000 to $200,000 the threshold for a Class B incident.

But the new guidelines left much open to interpretation by the services.

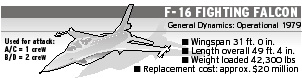

On Oct. 18, 1994, an F-16 sustained $1.8 million in damage when its landing gear failed at Moody Air Force Base, Ga. Because the damage was more than $1 million, it fit the category for a Class A accident.

Or so it seemed.

Former Lt. Col. Jerry Perkins, who retired in December 1994 as director of computer operations for the Air Force Safety Center in New Mexico, said he originally counted the accident in the Air Force database. He said he later was told by his supervisor that a general wanted the accident reclassified, making it disappear from official accident rate statistics.

"I objected to the point of being told to shut up and salute," Perkins said.

The rationale the Air Force used for not counting the accident was that the bulk of damage was to an expensive piece of equipment, called a LANTERN pod, used for night flying. Because the LANTERN pod was not a permanent part of the plane, the Air Force believed it didn't have to count the damage against the $1 million threshold.

The new directives also didn't clearly define when the services could exclude an accident because it occurred in combat.

During Desert Storm, the Air Force classified as combat losses the destruction of an EF-111 and an F-16.

Neither plane was hit by enemy fire. The EF-111 crashed after it took evasive action while being mistakenly targeted by a U.S. Air Force F-15, and the F-16 was destroyed when a bomb apparently detonated prematurely, although other possible causes were not ruled out.

The Air Force decision not to include the accident was subsequently questioned in a special management review, and the service has since changed its rules. In July 1994, the service expanded its regulations, making "friendly fire" accidents the same as combat losses: no longer kept in the official accident rate reported to the public and Congress.

'FLIGHT-RELATED' ACCIDENTS UNCOUNTED

One of the major categories of accidents addressed under the new regulations was "flight-related" -- accidents in which the damage, though substantial in some cases, is not considered directly related to the aircraft.

Between 1980 and 1998, the three services identified 961 flight related accidents, resulting in at least 26 deaths and 411 injuries.

Each case was identified as flight-related, signaling that they were not to be included in the so-called mishap rate, the number frequently provided to reporters and Congress by the military. Although the incidents were identified on computer databases, those databases previously had never been released outside the military.

The Navy had the most flight-related cases: 654 since 1980. Nineteen were Class A accidents that killed 11 people and injured 13.

On April 18, 1996, the tailhook of an F-14 landing on the USS Nimitz caught a wire, which struck and killed a sailor working on the flight deck and injured six others. On Nov. 16, 1995, the crew chief aboard a CH-53E Super Stallion helicopter flying a night-vision goggle training mission in North Carolina fell out of the aircraft and was killed, and on Aug. 9, 1992, near Reno, Nev., another crew chief was killed when he fell out of a helicopter on a night-vision goggle training mission.

All three accidents were termed flight-related and not calculated in the statistics frequently provided to reporters and Congress.

The Army had 225 flight-related incidents, killing 10 and injuring 87 others; most of the cases -- at least 161 of them -- occurred after the new rules took effect.

On Jan. 20, 1995, one soldier was killed and 21 others injured when they roped down from two helicopters into the wrong landing site during a night mission in a dense Louisiana forest.

SKIP PETERSON/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

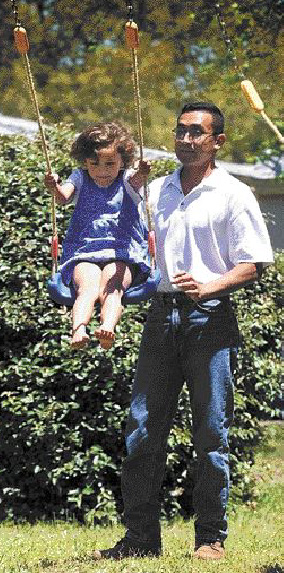

'I THOUGHT IT WAS COUNTED as far as Air Force accidents,' said Sanya Brockinton, who lost part of his right leg while parachuting in 1995. He was pulled out of the plane prematurely, hitting a horizontal stabilizer on the aircraft as he fell. Brockinton now lives in Florida with his family, including 4-year-old daughter Amanda (above).

SKIP PETERSON/DAYTON DAILY NEWS

'I THOUGHT IT WAS COUNTED as far as Air Force accidents,' said Sanya Brockinton, who lost part of his right leg while parachuting in 1995. He was pulled out of the plane prematurely, hitting a horizontal stabilizer on the aircraft as he fell. Brockinton now lives in Florida with his family, including 4-year-old daughter Amanda (above). |

On Jan. 3, 1992, a civilian kayaker was killed when he fell from an Army helicopter that was trying to hoist him from the water near a Texas dam where he had become stranded.

None of the accidents was counted in the Army's mishap rate.

The Air Force termed 82 cases flight-related, with at least 70 of them occurring since the new rules took effect. Five people were killed and 50 injured in Air Force flight-related incidents.

On Jan. 3, 1990, Army Private First Class Edward L. Suits, Jr., was killed when the right wing of a huge Air Force C-141 cargo plane hit his parachute over North Carolina. The aircraft sustained more than $6,000 in damage, but neither the Army nor the Air Force counted the accident in its official mishap rate.

"They tried to cover it up," said Suits' father, Edward L. Suits, Sr. "The worst part about it is that they wouldn't tell us anything.

"I was a paratrooper. I made four trips to Vietnam. I know about jumping, and I know they were negligent."

Suits said he was unaware his son's death was not counted in official statistics.

"I hope something is done about that," he said.

On March 17, 1995, Sgt. Sanya Brockinton was trying to parachute from an Air Force C-23A jet over California when he was pulled out of the plane prematurely, hitting and damaging a horizontal stabilizer on the aircraft as he fell. Brockinton, who was recently married with an 8-month-old child, lost the lower part of his right leg in the accident.

"I thought it was counted as far as Air Force accidents," said Brockinton, who now lives in Florida. "If a person got hurt and the aircraft was damaged, you think it would be."

NTSB attorney Matthew M. Furman said that if a civilian plane hits a parachutist the incident is counted in civilian accident statistics.

GROUND ACCIDENTS ALSO EXCLUDED

The military policy adopted in 1989 also allowed the services to exclude a larger number of accidents occurring on the ground. Prior to 1989, any incident occurring once an aircraft started its engines was counted in the mishap rate, but the new regulations require the aircraft to be moving on a runway and to have an "intent for flight." Helicopters have to be off the ground.

The NTSB policy is much more far-reaching, counting every accident occurring after someone steps aboard an aircraft, regardless of whether an engine is running.

In 1997, for example, the NTSB counted as an aviation death an incident in which a ground crew member was struck by a Delta Airlines L 1011 that was being towed and not operating under its own power.

At least 42 of the Navy cases, in which nine people were killed and 23 injured, were cases likely to be counted by NTSB.

|

The Navy also classified as a ground mishap the much publicized Sept. 6, 1996, accident in which a CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter struck a light pole, rolled over and burned at Orlando Executive Airport. It was second accident in a single day involving a military helicopter assigned to support President Clinton's trip to Florida, and the president immediately ordered a top-to-bottom review of all aircraft assigned to the White House.

During a press briefing the same day, a Pentagon spokesman in Washington gave reporters the mishap rate for the type of helicopter that burned in Orlando. That rate did not include the very type of accident the reporters were asking about: the Sea Knight that was destroyed after hitting the light pole.

Between 1980 and 1998, the Army classified 269 incidents as ground accidents, seven of them Class A accidents resulting in five deaths. Five of the seven Class A accidents occurred since the reporting rules were changed and in at least four of those cases, records indicate the engines were running when the accidents occurred.

In 1996, an Army doctor was struck by a helicopter rotor blade and killed while the aircraft was being refueled. Though the helicopter's rotor blades were turning, the accident was classified as a ground accident and not counted in the mishap rate.

The Air Force not only excluded ground accidents from its official accident rate but until Oct. 1 of this year also kept them from its aviation database altogether. Prior to Oct. 1, the service counted aviation ground accidents in a separate database along with automobile and truck accidents.

At least 20 aviation ground accidents, each causing at least $100,000 in damage, were reported by the Air Force between 1988 and 1998.

One of the Air Force cases excluded from its database occurred on Dec. 3, 1996, when Navy Seal Theodore M. Moreland was killed after he was thrown from an Air Force C-17 as the door to the jet blew open.

Told her husband's death wasn't counted as part of the official accident rate, Moreland's widow, Tracy, said: "You're kidding."

Sections: 1 2 3