Penalties few for poor care

Nursing homes usually prepare for 'the game'

|

© 1999 Dayton Daily News|

When state inspectors walked into the Bethany Lutheran Village nursing home in October, they didn't hear complaints about staffing problems. They didn't find any incident reports in charts. And if they learned anything they didn't know, it wasn't because some staff member volunteered the information.

That's because at Bethany, officials have made a science out of preparing for the annual visit from the Ohio Department of Health.

LISA POWELL / DAYTON DAILY NEWS

LISA POWELL / DAYTON DAILY NEWS

Cost often dictates elder care choices |

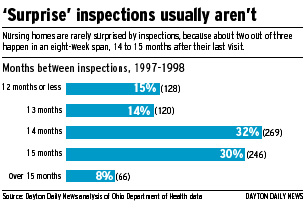

State inspections have become "this little game played out every year, because the surveyors never see the conditions that are the norm for the other 50 weeks of the year," said a staff member at the 315-bed facility, who asked not to be named. "And it's not just Bethany, but a common, industry-wide routine."

An eight-month Dayton Daily News examination found that Ohio's nursing home regulatory system fails to protect its most vulnerable charges. It's a system where nursing home operators have little to fear from the people who police them and plenty of opportunities to hide bad care.

For example:

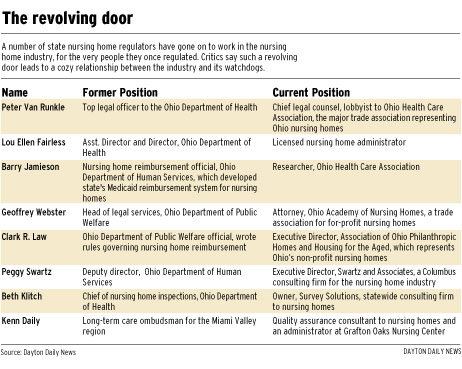

"When (state employees) go to the other side, which happens all the time, their job is to tell providers how to stay within the law and, at the same time, how to get around the law -- 'legally,' I guess," said Gerson Silver, a family counselor in the Montgomery County court system who once headed the nursing home complaint division of the Ohio Department of Human Services.

There's nothing cozy or unethical about the industry recruiting from the ranks of its own regulators, said Peter Van Runkle, chief legal counsel and lobbyist for the Ohio Health Care Association, the major trade association for Ohio's nursing homes. Van Runkle, as the former top legal adviser to the Ohio Department of Health, was once a regulator himself.

"If you looked at any other industry, I think you would find the same thing," he said. "Where do you find the people who have the expertise that you need?"

State health department officials also said Ohio is a national leader in collecting fines.

"We feel we're pretty aggressive in our enforcement scheme in Ohio," said Alan Curtis, chief of the health department's bureau of regulatory compliance.

"Our goal, collectively as a division, is not to put facilities out of business but to encourage them to comply and improve their quality of care," said Kurt Haas, who heads the department's inspections office.

Haas said the department has stepped up its educational services to the industry, offering seminars, speakers and brochures on such topics as how nursing homes can reduce bed sores, falls and the use of patient restraints.

"There have been some very good outcomes that don't just come from enforcement, enforcement, enforcement," he said.