A tale of two unions

Dayton's IUE believes the UAW is destroying itself, while Saginaw's UAW believes the IUE has sold its soul to GM

By Mike Wagner, Rob Modic and Wes Hills Dayton Daily NewsPublished: Monday, December 14, 1998

Series - Part 2 of 4

SAGINAW, MICH. - It wouldn't take much for Brian Daly to climb down from the

roof of a grain elevator and move to the top of a list of 200 men who want a

skilled trades job at the largest General Motors factory in Northern Michigan.

All it would take is a phone call from his dad.

It's a call Bill Daly will never make.

`If I ask GM for a favor, they'll want a favor in return and that would mean I'd have to sell out new workers in our plants,' said Daly, president of United Auto Workers Local 699, which represents 6,700 workers at GM's Delphi Saginaw Steering Systems.

That don't-give-an-inch attitude toward the largest employer in this city of 70,000 characterizes the UAW and shows how different it is from its much smaller rival, the International Union of Electronic Workers. It also marks the difference between Saginaw and another city fueled by the production of automobiles: Dayton.

The IUE, which represents 12,000 Dayton-area autoworkers, has embraced reducing wages for newer employees to preserve jobs.

The UAW, which represents the same number of autoworkers in Saginaw, has taken a militant stance against tiering wages.

`I love my son, but there's no way in hell we're ever going to accept the kind of contracts some unions have taken in Dayton," Daly said. "We've told GM where they can stick tiered contracts for years and that won't change.

`And there ain't no guarantees that accepting low wages and benefits for young kids will keep jobs in the plant.'

But the UAW's opposition to tiers hasn't kept jobs in Saginaw's plants either. In the past two decades Saginaw has lost nearly half of its 22,000 GM jobs, and nobody expects them to return.

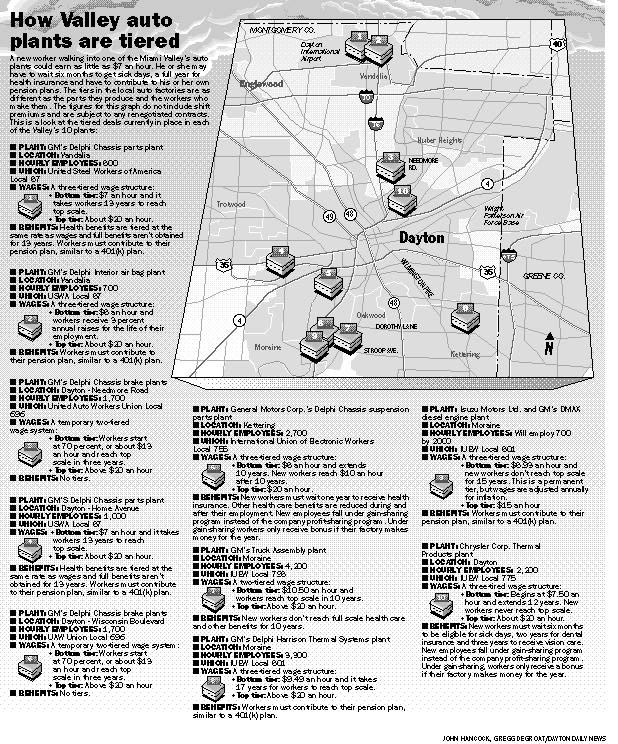

Dayton, meanwhile, remains one of the largest automotive meccas in America. There are 20,000 GM workers and 2,000 Chrysler workers at 10 plants in the Miami Valley.

The Chrysler plant has more than doubled its workforce since its union agreed to tiering wages in the 1980s. Production is booming at the Moraine truck assembly plant, which will build GM's next generation of sport utility vehicles. And a new diesel engine plant, already under construction, is scheduled to open in 2000.

None of this would likely have happened if the IUE hadn't agreed to contracts that tier wages and benefits for new workers.

Those contracts dramatically lower labor costs in each of those plants. New hires in Dayton's auto plants can work the same assembly lines as older workers making nearly three times their wages, and they can wait up to 17 years to reach the top of the pay scale. They also have to wait longer for health benefits, and some workers never see the annual bonus check cut to those working in plants without tiers.

The mere mention of Dayton's tiered wage contracts in Saginaw draws fury. Many Michigan auto workers believe Dayton's local labor unions have eaten their young to survive.

`If union leaders had accepted deals like GM wanted 10 years ago they would have been searching for their body parts and I'm serious about that,' said Manny Barajas, an hourly worker at a Delphi engine plant in Saginaw. `Those deals are union killers. Workers know it. The company knows it.'

A STEADY DECLINE

When Delphi's presence in Saginaw was at its peak, Bill Shinaver used to have to stand in line to get a beer at McCabe's tavern. McCabe's sits across the highway from one of Delphi's biggest steering parts operations and has been the favorite after-work drinking hole for thousands of local workers.Ten years ago, McCabe's tables were filled within 20 minutes of a plant shift change and it was hard to hear Lynyrd Skynyrd blaring from the jukebox.

`You had to order three beers at a time back then because it would take you a half-hour to get back up to the bar,' said Shinaver, in between sips of Jack Daniels and Budweiser.

Now Shinaver and his friends can order one Bud at a time and they have

their pick of any table. That's because Delphi's Saginaw Steering Division has

shrunk to about 6,700 now from 10,500 workers in 1980. And union leaders

expect at least 1,500 more jobs to disappear in the next two years when older

workers retire.

Now Shinaver and his friends can order one Bud at a time and they have

their pick of any table. That's because Delphi's Saginaw Steering Division has

shrunk to about 6,700 now from 10,500 workers in 1980. And union leaders

expect at least 1,500 more jobs to disappear in the next two years when older

workers retire.

The Bill Shinavers of Saginaw are a dying breed. By his 19th birthday Shinaver had graduated from high school, married, landed a job on a Delphi assembly line and become a father. He has spent 27 years in Plant 3 of the steering division and brags about putting his two daughters - one a nurse, the other a school teacher - through college.

`Kids today have little or no chance of getting a GM job in Saginaw,' Shinaver said. `The older workers retire and GM doesn't replace them because we won't vote for a two-tier system.'

Saginaw has been steadily hemorrhaging GM jobs for two decades.

All of Saginaw's remaining Delphi operations have seen a steady decline since the mid-1980s.

The Delphi Chassis Systems Saginaw plant, which makes brake parts, has gone to 1,400 workers from 2,500. A GM Powertrain Malleable Iron plant has lost about half its workforce and now employs about 1,000 workers. But the biggest drop has come at the Saginaw Metal Casting Operation, formerly known as the Grey Iron Foundry, which once employed 7,500 and now operates with less than 2,000 workers.

GM also closed Saginaw's Nodular iron plant in 1987 after just 19 years of production. It was then demolished a few years later and only a few piles of bricks remain where the plant once thrived.

But losing jobs from its most important economic base is not a problem only Saginaw faces. More than one-half of Michigan's Big Three autoworkers - about 129,000 workers - will be eligible for retirement by 2003, according to a University of Michigan study. The Big Three won't replace many of those jobs, and old line industrial communities like Saginaw could feel the sting for decades.

With 1,400 employees, Ameritech is the only other significant corporate employer in Saginaw.

`GM is slowly moving out and Saginaw will be left to die in about 10 years,' predicts Curt Thompson, who's worked for 29 years in Plant 4 of Delphi's steering division.

Still, older union bosses here say they don't regret rejecting GM's wish for reduced wages for new hires.

`Yeah, I know we've lost of ton of jobs, but what the hell good are jobs where young guys are working ... for $8 an hour?" said Jack Campbell, who retired three years ago as an International UAW representative. "You can't buy a house, you can't by a car or raise a family the right way on a wage like that.'

But even the union-hardened Campbell, once one of the most feared local UAW leaders in the country, admits he almost gave in to a two-tier system to save jobs.

It was the mid-1980s and GM told Campbell the company would sell Plant 1 of Delphi's Saginaw Steering Division unless the union agreed to a new wage agreement. The agreement gave existing workers raises but slashed pay for new workers.

Campbell told GM he would support their demands and presented the plan at a membership meeting held at the Saginaw Civic Center.

`They almost ran me off the stage because they knew what that crap would do to young workers. They knew it was poison for a union,' Campbell said.

Following the meeting, Campbell told GM the union wouldn't accept the tiered system. Three weeks later, the plant was sold and 170 jobs were gone.

`We wouldn't have been in those situations if the IUE had not caved into GM," said a bitter Campbell. "The IUE was told not to adopt that, but they did.'

TALE OF TWO UNIONS

The story of Dayton and Saginaw is a tale of two unions that don't like each other. The UAW believes the IUE has sold its soul and its young members to GM, while the IUE believes the UAW is destroying itself by losing plant after plant because of its refusal to compromise.Plant closings, downsizings and the exporting of jobs to Mexico and elsewhere have struck both unions, but the UAW has taken more hits lately. Since 1980, the UAW has seen its GM ranks shrink from 450,000 jobs to barely 200,000.

"The UAW has their way and I respect that, but we have our way too, and it's a way that has saved plants and communities,' said Mike Bindas, a Dayton-based leader of the IUE who negotiated one of the auto industry's earliest tiered contracts.

All of the IUE-represented GM plants in the Dayton area operate under tiered wage deals that pay new workers as low as $7 an hour, while veteran workers earn about $20 an hour. UAW plants are tiered also, but the wage disparities are smaller and more temporary. In Saginaw's auto plants, new workers are paid nearly $13 an hour, or about 70 percent of the top wage, and can make top wages of $20 an hour within three years. At IUE plants, it can take as long as 17 years.

The difference in the unions' philosophies was never more evident than during the past three years, when both were fighting GM to save three troubled Dayton-area factories.

Huge financial losses had caused GM to target two Dayton brake plants and a suspension parts plant in Kettering for sale or shutdown starting in 1996. The 3,400 workers at the brake plants are represented by the UAW, while the 2,700 Kettering workers are represented by the IUE.

To save the brake plants, the UAW went to war with GM. To save the Kettering plant, the IUE turned to tiering.

UAW Local 696 staged a 17-day strike that cost GM nearly $1 billion. The strike was settled when the two sides agreed on how much work would be outsourced to non-union automotive suppliers. Local 696 also marched with workers in Flint, Mich., when they staged a 54-day strike this past summer and shut down GM's North American production.

In the end, Local 696 suffered the same fate as the unions in Saginaw and other places where the UAW has rejected a huge gap in wages. The brake plants will lose nearly half of their 3,400 jobs in the next three years as workers eligible for retirement accept a $25,000 buyout from GM. Those jobs could be replaced, but analysts say that's unlikely considering workers in the plants still earn close to $20 an hour after three years.

Meanwhile, IUE Local 755 was taking a less militant approach to saving its plant. Union leaders and plant officials worked together for more than two years to develop a `fix it' plan to keep jobs from being shipped to Mexico and prevent the plant from being sold.

In the end, the Kettering plant was spared, but the new contract hammers new workers. The three-tier contract means young workers will see big cuts in wages, health benefits and profit-sharing plans. New workers also will be paid $8 an hour under the plan, and won't reach $10 an hour until they work at the factory for 10 years.

`Whether you reject tiering and lose jobs or accept tiering and pay new workers low wages, none of it does much good for unions,' said Harley Shaiken, a labor expert for the University of California at Berkley. "This isn't an issue that will not go away for labor unions."

STILL A GM TOWN

Throughout this decade, most of the Dayton area's GM plants have been on or near death row.Tiers were a successful last line of defense.

The most serious threat came in 1991 when GM announced it planned to close 21 plants in North America. On that list was the Moraine truck assembly plant, the Miami Valley's largest factory. The plant employs 4,200 hourly workers and makes some of GM's best-selling sport utility vehicles.

State and local governments rallied together and collected $45 million in grants, loans and other financial incentives to build a new paint shop for the truck plant. A booming truck market was another factor in keeping the plant open.

But in the end, it took a two-tier wage agreement, which pays new workers about $10 an hour, to save the factory. The Moraine factory remains the only GM assembly plant in North America to operate under a two-tier system.

`Without that deal the plant was dead,' said Jim Marlow, an IUE former shop chairman at the truck plant.

Tiered contracts were again the difference this year when Moraine nearly lost its diesel engine plant and 700 jobs. The plant was making a diesel engine in a dead market and was losing jobs at a rapid rate. The plant had gone from more than 1,000 jobs in the early 1990s to about 500 because of lost contracts.

Then GM announced it was turning over its world-wide diesel engine development and production to Isuzu Motors Ltd. Together, the two automakers would build a new diesel plant.

Moraine was among the possible sites for the plant, but became the only candidate for the $310 million project when its union agreed to a permanent three-tier wage contract that will pay new workers about $8 an hour. The plant is now expected to open in 2000 and employ at least 700 workers.

`Some people are going to criticize our unions for accepting these kind of contracts, but I know there a lot of other cities that would like to have the number of GM jobs we do,' said Moraine Mayor Roger Matheny.

`GM is not the bully here in Moraine. They have given thousands of families here a chance for a better life and we have helped them out when business gets tough.'

RETIREMENT PARTY

About 400 retirees crammed Saginaw's largest union hall a few weeks ago to share an early Christmas dinner and play bingo. They talked about life in their old plants, debated whether President Clinton should be impeached and exchanged pictures of their grandchildren.Then one union member brought in the local afternoon newspaper, and many of the retirees quickly lost interest in their bingo cards.

Another GM plant was closing.

Delphi announced it would close Plant 2 of its Steering Systems by mid-2001 and shift 1,500 jobs to another local plant. The plant, built in 1941, is not just another factory to many of the retired workers. Before making steering components, Plant 2 was known as the `gun plant' where workers started cranking out .30 caliber Browning machine guns and M-1 rifles to support soldiers in World War II.

Henry Ruppel, among the first workers to be employed in the closing plant, shook his head in disgust when asked about the factory's death sentence.

`There was a lot of work in that plant, yep, there used to be a lot more work in all of our plants,' said Ruppel, 84, chairman of retirees for UAW Local 699.

`Saginaw used to be one of the biggest GM cities in America, but when old guys like me leave the (assembly) lines the jobs go with us,' said Walter Albin, 79, who retired from Plant Five of Delphi's Steering Systems in 1984.

In Dayton, the jobs haven't left yet, but a job at GM no longer guarantees a comfortable retirement.

"The choice is definitely between lower-paying jobs and closing factories," said John E. Weiler, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Dayton. "What's better? In the short run it's better to have a job than no job at all. But those are not desirable jobs in the long run."

Jim Schuyler, 52, spent 25 years at the former Hobart PMI plant in Troy, and was earning $18.50 an hour when the plant was sold. In March 1997, Schuyler landed at GM's Delphi Chassis parts plant in Vandalia, making $7 an hour as a bottom-tier worker. He now makes $10.34 an hour, and is facing annual raises of about a dime an hour over the next nine years.

Schuyler, a father of two and grandfather of four, won't reach top scale until he's ready to retire.

`These tiers are killing guys like me,' he said. `And it's only going to get worse.'

Sidebar:

INTERVIEW

Expert: Wage shift saved jobs in Dayton

* An automotive expert says the foresight of the IUE led to the acceptance of tiered wages, and kept jobs in Dayton.Part Three:

Low skill levels mean low pay

Unless workers can offer more than just muscle, they will dwell in the bottom pay rungs.