Disappearing wages

Tiering took off in the early 1980s. Now more than 2 million workers are in jobs with multiple wage classes

By Wes Hills, Rob Modic and Mike WagnerDAYTON DAILY NEWS

Published: Sunday, December 13, 1998

Series - Part 1 of 4

Stan Flaherty is sandwiched on a Dayton assembly line between two guys

making $20 an hour.

He makes $8.

Jim Schuyler lost his job of 25 years when a Troy manufacturing plant was

sold. Now, he has a similar job but makes half as much as some of his new

co-workers.

Stan Williams returned to his job as a bus driver in Los Angeles, where he

worked for nine years, and is receiving $10 an hour - half what other veteran

drivers earn. And he is ineligible for full health-care benefits for his

family.

Thousands of workers in Dayton, and tens of thousands more across the

country, perform the same work as the person next to them, work the same

hours, but earn less pay.

Often dramatically less.

The pay scales - called two-tier, three-tier and even multitier - aren't

based on the quality of employees' work or their experience, but on a single

factor: their hiring date.

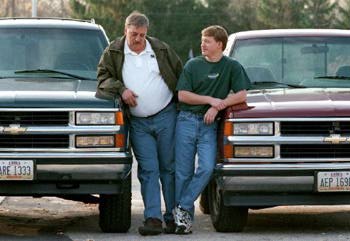

O.D. Robinson (left) and his son Jason both work at Harrison Radiator.

They both buy GM cars and trucks, but their pay is very different. Jason is

attending Sinclair Community College to get a better education and find a

better job.

SKIP PETERSON / DAYTON DAILY NEWS

The later the hiring date, the lower the pay.

The cost-cutting strategy has saved thousands of jobs and allowed blue-collar towns like Dayton to maintain their manufacturing base. But it also pits worker against worker on factory floors, college campuses, farms, highways or anywhere unskilled workers are stuck in low-paying jobs.

In a booming economy, these workers are increasingly left behind.

"How the hell do they expect us to live and raise families on less than $17,000 a year?," said Flaherty, 29, who earned more in weekend tips as a bartender than he does in a week at his job at the Dayton Chrysler Corp. plant.

Flaherty makes $8 an hour as a bottom-tier autoworker because members of his union, under the threat of a plant shutdown, voted to protect older workers while slashing pay and benefits for those coming in at the bottom of the seniority ranks.

Tiered wage agreements such as this one are a fixture in the U.S. automotive industry, and all 22,000 autoworkers in Dayton now work under a tiered contract.

But tiering has extended far beyond the auto industry as competition in an increasingly global marketplace forces companies to find ways to increase productivity and reduce labor costs. A third of all union contracts now includes some form of tiered wages, including nearly two-thirds of those in the Midwest, according to a 1997 Bureau of National Affairs survey of 147 employers across the nation.

Tiering is also sweeping through businesses without union contracts. Numbers are hard to come by because neither the government nor industry groups track tiering, and individual businesses don't like to admit they have tiers.

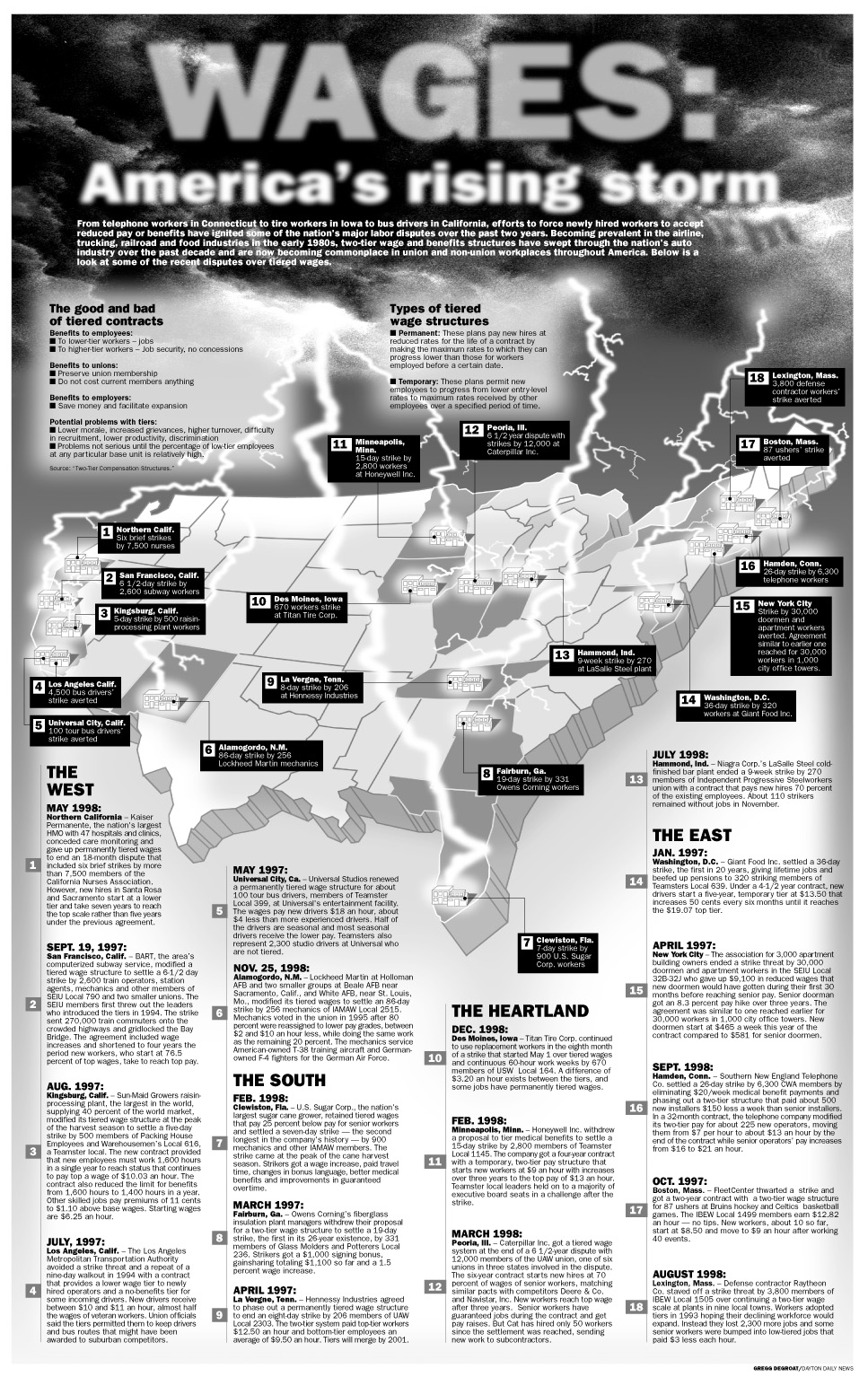

But a Dayton Daily News review of 200 labor disputes and hundreds of interviews identified more than 2 million workers who are in jobs that have two or more wage tiers. Since tiering took off in the early 1980s, two-tier wage plans have penetrated just about every trade, both skilled and unskilled - from thermostat makers in Minnesota to nurses in New Jersey to bus drivers in California to sugar-cane processors in Florida. And in the past two years alone, tiering has led to strikes and labor confrontations in more than a dozen states.

For example:

* In Los Angeles, the city bus authority averted a repeat of a 1994 walkout by drivers by cutting a deal with the union. But the contract pays new drivers $10 an hour - about half what veteran drivers make.

* In New York City, 30,000 doormen and apartment workers agreed to a contract that gave older workers an 8.3 percent raise while cutting wages for new workers by $9,100 over a 30-month period.

* In Minneapolis, Honeywell Inc. settled a 15-day strike by 2,800 thermostat-makers and other employees by withdrawing a proposal to tier medical benefits. However, the four-year contract calls for a two-tier pay structure that starts new workers at $9 an hour, with increases over three years to a top pay of $13 an hour.

Bob Sutton, shop chairman of the International Union of Electronic Workers Local 717 in Warren, Ohio, said tiered benefits at General Motors' Packard Electric Division put a $500,000 lifetime medical insurance cap on bottom-tier workers.

Sutton recalled how the cap devastated one of his union members.

`The guy was crying to me," he said. "He proceeded to tell me he lost his wife to cancer and her care at the Cleveland Clinic had drained all of his $500,000 lifetime insurance cap. Here he is with three young boys and no health care."

Fast-food wages

Companies have good reasons to squeeze costs. Increased competition, coupled with low inflation, is forcing businesses to hold the line on prices. A 1999 Acura 3.2TL, for example, is $5,200 cheaper than the 1998 model. GM held the line on most 1999 models. The average price of a Saturn is down about $100 from last year.

Companies are consolidating production lines, shifting facilities and

streamlining operations to boost productivity and profits. But high labor

costs are the biggest target, particularly where competition is keeping the

lid on prices.

Companies are consolidating production lines, shifting facilities and

streamlining operations to boost productivity and profits. But high labor

costs are the biggest target, particularly where competition is keeping the

lid on prices.

"I think companies would like to pay a uniform wage rate, if they could," said David Cole, director of the Office for the Study of Automotive Transportation at the University of Michigan and a regular consultant to GM. "I don't think they want to destroy unions. That kind of thinking has passed. The dominant issue today is how can we be competitive."

Supporters of tiered wage structures say reduced labor costs not only keep companies competitive, they preserve jobs.

When Dayton's Chrysler plant was on the block and employment dipped to 700 in 1988, a three-tier contract saved the plant. It now employs 2,000 workers.

`I think (automakers) came to realize some of the competitive realities in its industry, particularly in the challenges facing automotive suppliers,' said Cole, whose father was president of GM from 1968 to 1974. `They just couldn't continue paying workers $20 an hour and stay competitive.'

Tiered wage plans save companies money because they can legally replace the $20-an-hour workers who retire with younger workers who may work faster and cost a lot less.

For older workers, it's a small trade-off: a better retirement in return for concessions that don't affect them.

But as younger workers rise up through the ranks, reaching a majority in some unions, the issue is exploding onto shop floors and at bargaining tables throughout America.

Last year, union members at Dayton's Chrysler Corp. plant voted Wes Wells out as president of International Union of Electronic Workers Local 775. Wells, president since 1967, negotiated contracts that put a generation of workers under two- and three-tier wage systems that will extend well into the next millennium.

Wells said he had no choice. It was swallow hard and accept tiers or lose the plant.

But while the agreements may have saved jobs at Chrysler, many workers in the plant's bottom tier found themselves making fast-food wages.

Colette Smith of Kettering left her job at Taco Bell a year ago after her uncle helped get her a job at the Chrysler factory.

`The fast food business was going nowhere for me, and I thought I was going to a big car company to make big money,' she said. `But when I got the information packet that told me what I would be making, I couldn't believe it when I saw $7.50 an hour. I made more at Taco Bell than I was going to at Chrysler.'

Smith now earns $8.50 an hour at Chrysler making parts for air conditioners.

"I'm not going to lie about it. Those contracts have really crushed morale for our workers," said Robert Price, who replaced Wells as Local 775 president. "The contract and wages for workers at the bottom tier are serious problems here."

Tiering lit the fuse for some of the most explosive strikes in the nation during the past year and a half.

Charges of unequal pay and benefits for the same work served as the rallying cry of strikers in 1997 during the International Brotherhood of Teamsters' bitter dispute with United Parcel Service. And when pilots walked out of Northwest Airlines' passenger jets in September, it was over a disparity in wages between veteran and recently hired pilots.

Tiering also led to organizing efforts for thousands of non-union workers. In July, four years after United Airlines began tiering wages for new reservations takers, agents and ticket sellers, 18,000 of those workers voted to join the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers.

Wage inequities imposed by American Airlines also ignited the organizing drive this year that led to 15,000 employees voting by mail about whether to join the Communications Workers of America. The votes will be counted Tuesday after a month-long period for casting mail ballots.

Statistics unreliable

Tiers come in all sizes. Some lock new employees into permanent tracks of wages and benefits that never reach the top pay of their senior co-workers. Others postpone attaining the top pay and benefits for two, three, four or more years.At GM's Delphi Harrison Thermal Systems plant in Moraine, new workers must wait 17 years to reach top pay. It's 13 years at GM's Delphi Chassis plant in Vandalia.

The Daily News identified more than 2 million workers under tiered contracts by examining national labor contracts and reviewing where tiers have resulted in strikes and other labor disputes. A high percentage of the nation's 1.4 million members of the United Food and Commercial Workers union work under tiered contracts. Another 500,000 autoworkers, 366,000 postal workers, 220,000 letter-carriers, and tens of thousands of Teamsters, steelworkers, rubber workers and airline employees are among unions that have tiered wage or benefit structures in their contracts. It's likely that millions more work under tiered wage structures.

Finding how many American workers are tiered is virtually impossible because no government agency monitors tiered wage structures or their effects, and labor organizations and employers go to great lengths to conceal how their workers are being paid.

The government releases little information about tiering. Shortly after President Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, the U.S. Department of Labor began to reduce its reporting on developments in labor contracts, which had served as one of the few peepholes on trends in worker compensation.

As a result, statistics regarding the number of workers in tiered union contracts grew increasingly unreliable. And there is no information collected by the Labor Department about wage structures for nonunion workers, who now dominate the American work force.

Companies are generally reluctant to discuss tiering. General Motors Corp. didn't allow any of its top executives to be interviewed for this story.

But there's another source for the lack of information: the unions themselves.

Many leaders of international unions, including officials at the collective body, the AFL-CIO, said they keep no figures on the number of members working under tiered contracts. Other union officials declined to discuss them.

And while labor experts, company executives and union officials all accept the phrase `two-tier compensation structures' as the proper description of wage structures that pay new employees less for some period of time, almost no one calls them tiered structures when they are installed in their own plants.

When GM's Delco Products plant in Rochester, N.Y., implemented tiered wages in 1983, the new wage structure was called the `Progressive Hiring Plan.'

When a tiered wage plan showed up at Dayton's Chrysler plant, it was called `Building Employment Security Together.'

In 1984, American Airlines labeled its first tiered contract for pilots `market wages,' a reference to the anticipated competition as long standing industry regulations were scuttled.

A history of tiering

Tiering dates to the Roman Empire, when Marcus Opellius Macrinus, the 23rd Roman emperor after Julius Caesar, imposed the earliest known two-tier wage structure on new recruits in his Army in 218 A.D. The plan led to his execution.Tiering didn't become widespread, however, until the past two decades of the 20th century, when the airline, trucking, railroad and food industries all adopted tiers. Some of the biggest wage disparities surfaced in U.S. auto plants.

Wage tiering in the auto industry dates back to 1981, when GM's Packard Electric Division, the largest employer in the Warren area, announced it intended to reduce its 9,000 workers to 5,200 by eliminating 3,800 `noncompetitive' jobs by 1986.

It was the second blow in a decade to that work force, which had numbered 14,000 workers in 1973 when the company announced labor costs were too high and began shedding workers. At the same time, Packard built two plants in Mississippi and three in Mexico.

That's when a union militant at the Warren plant, Mike Bindas, came up with what became known as the `Final-assembly Option.'

Bindas proposed a permanent, lower-tier wage for new workers.

At first, Packard workers in Warren rejected a tentative pact in 1983 that called for new hires to receive $4.50 per hour, plus $1.50 in benefits. That was less than a third of the $19.60 an hour paid to workers hired before the agreement.

But about the same time, GM presented a tiered contract proposal to employees at its Delco Products plant in Rochester, N.Y.

`It was a terrible time for the auto industry,' recalled Joe Giffi, president of lUE Local 509 at the Rochester plant. `We had 4,000 members, and 1,800 were on permanent layoff.'

Tiered contracts were eventually adopted at the GM plant in Warren and soon after at Dayton's Chrysler plant. By the end of 1996, eight more Dayton auto plants had implemented tiers.

Today, Dayton is one of the country's most heavily tiered cities, with thousands of school bus drivers, grocery store clerks, produce workers and machinists working under tiered contracts. The Miami Valley has more than a third of its work force in blue-collar jobs - well above the national average - the people most susceptible to tiering.

But Dayton is also one of the few automaking cities in America dominated by the IUE, which has OK'd huge gaps in wages or benefits between new and older workers in plant after plant.

While the IUE has embraced tiered contracts as a necessary protection against further job losses, the rival United Auto Workers has traditionally taken a hostile stance against them.

Saginaw, Mich., has paid the price for that stance. There, the UAW said no to long-term tiers, and nearly half the city's 23,000 automotive jobs have disappeared since 1980.

Without tiering, "I don't think Dayton would have a fraction of its jobs," Cole said. "Tiering has been the key factor in Dayton keeping its high employment level."

The IUE, said Cole, "has a better understanding of the broader business picture than the United Auto Workers."

But even the UAW has bent on its stance against tiers. The union, based in Detroit, has lost about half its 1.5 members since 1970 as the Big Three automakers moved tens of thousands of jobs to Mexico, China, Korea and other countries. But the UAW has agreed to temporary tiers, where new workers can make $20 an hour within three years.

Former UAW President Doug Frazer said his union resisted tiered contracts `as best we could, and we were successful until very recently.'

Frazer said the IUE acceptance of tiering in the auto industry in the 1980s put tremendous pressure on the UAW to make similar concessions.

`It's very difficult for us to take,' Frazer said. `It's extreme."

Bill Bywater, who stepped down in 1996 as the international president of the IUE, said tiering can't stop a company that wants to move jobs elsewhere.

`I was never for tiering,' he said. `The main reason for tiering was the company threatening to move jobs to Mexico or some other place. They ultimately did, anyway.'

Ed Fire, who succeeded Bywater and is the current IUE international president, called tiering a "necessary evil."

"I don't pretend that everything we've done has always been right," he said. "It's a sad commentary on society that we have to face lowering wages for new workers. But the alternatives were much worse. We saw this as the least painful way to save work."

Another option

Not every business pits worker against worker when slashing labor costs.At the innovative Nucor Steel plant in Crawfordsville, Ind., production workers earn an average of $75,000 in profitable years. But their pay is slashed when production diminishes or the market for steel declines. And when business is bad, even Nucor executives suffer salary cuts.

But under its `share the gain/share the pain' plan, the company has never sent a worker to the unemployment line or moved jobs overseas.

At the four nonunion Honda of America plants in Ohio, autoworkers reach $19.60 an hour within two years. Honda officials said their work philosophy would never permit them to consider wage tiers that pay production workers different wages for the same job.

`We have never even entertained the thought of a tiered wage system,' said Tim Garrett, vice president of administration of Honda of America Manufacturing. `... I don't think that is an image or an idea that we really would look at as being viable within our operation.'

Honda also has avoided layoffs.

Where tiering has been used, it's also been used discriminately.

Executive salaries have been largely undisturbed by tiering. United for a Fair Economy, a nonpartisan organization founded in 1994 to focus attention on economic equality in the U.S., found that the chief executive officers of the 10 companies that moved the most jobs from the U.S. to Mexico earned average salaries and bonuses in 1997 of more than $3 million - a 15 percent increase over 1996.

Tiering hasn't hurt union executives either. Salaries of some union leaders swelled to more than eight times the annual earnings of their lowest-paid members on the bottom of tiered wage structures.

And some unions, like the IUE, don't tier their members' dues even when they work under tiered contracts. Workers at the bottom tier pay the same dues as co-workers who earn up to two and three times as much.

Despite the controversy about tiering, however, it has withstood every legal challenge. No state or federal law protects new workers simply because they were the last to be hired.

"If it's simply the newly hired people being paid less than those already hired, I don't think you'll ever get a court to upset one of them," said Clyde Summers, a University of Pennsylvania Law School professor.

Sharing the pain

Former U.S. Secretary of Labor Robert Reich said workers who wish to fight tiers face an uphill battle."If younger workers are relatively unskilled and in abundant supply relative to the demand for them, their wages are heading south," he said. "That's been the story in this country for the last two decades. American companies, indeed all companies, are focusing on the bottom line like never before. Labor costs typically constitute about 70 percent of the cost of production. So you can bet that executives are going to be looking for every possible way to reduce labor costs."

Unions, particularly those in industries with global competition, have limited options, Reich said. They can fight a "rear-guard" action against outsourcing, two-tiered wage contracts, downsizing and other cost-cutting measures, or upgrade the skills of their members and seek to tie pay levels to productivity and profitability, he said.

But tiering is probably here to stay, according to Reich.

"Anyone who thinks someone can waive a magic wand and prevent tiering doesn't know much about the economy or who has economic power these days," he said. "The real problem is that too many Americans are still on a downward escalator."

Andy Lieffring of Miamisburg is one of those Americans. Originally from a farm in Wisconsin, Lieffring, 25, moved to Cedarville in 1994 to attend college, where he met his wife, Kimberly. They got married,

Sidebar:TIER CONTRACTS TEAR WORKERS APARTPart 2:2 CITIES, 2 CHOICESThere are no easy answers when it comes down to fewer jobs or lower wages. |

There are three tiers at the plant and Lieffring is at the bottom.

"I have a child. My wife doesn't work and I couldn't even get health insurance for my family for eight months," he said. "We got sold out. It's that simple.

"And the future doesn't look much better for guys like me."