By Russell Carollo and Jeff Nesmith

Dayton Daily News

Published: Wednesday, October 8, 1997

Series - Part 4 of 7

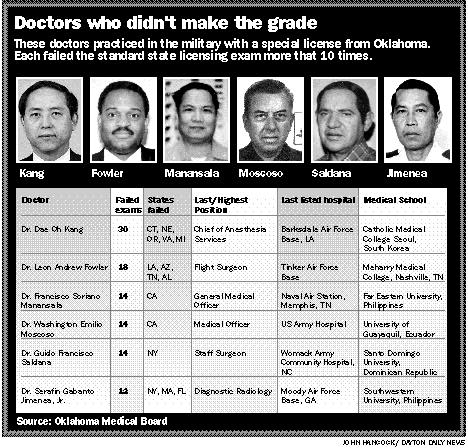

OKLAHOMA CITY, Okla. - Dr. Leon A. Fowler delivered Domino's pizza, worked

in a furniture store and made sales pitches over the phone as a telemarketer.

He had a medical degree, but he failed the standard state medical license

exam 18 times - in Louisiana, Arizona, Alabama, Tennessee and Oklahoma. He

also was expelled from his residency program at Oral Roberts University

hospital after failing one of those exams.

He had a medical degree, but he failed the standard state medical license

exam 18 times - in Louisiana, Arizona, Alabama, Tennessee and Oklahoma. He

also was expelled from his residency program at Oral Roberts University

hospital after failing one of those exams.

Dr. Washington E. Moscoso failed 14 times, results one state medical board said `raise serious issues as to the applicant's ability to practice medicine and surgery with reasonable skill and safety.'

Fowler, Kang and Moscoso all found an employer willing to let them practice medicine. And so did dozens of other doctors unqualified to treat civilians.

The employer was the United States armed services.

The military in 1988 began requiring its doctors to get state medical licenses so that military doctors would meet the same standards as civilian doctors. Because military doctors are constantly transferred, they weren't required to be licensed in states where they practiced, as civilian doctors are. A license from any state allowed them to practice at any of the military's almost 600 hospitals and clinics worldwide.

As physicians scrambled across America looking for states to license them, one state, Oklahoma, made a special category. The Oklahoma medical board granted "special licenses" to military doctors who did not meet minimum licensing requirements. Medical board officials said they took the step because they felt the special licensees were not a threat to patients and the military needed doctors. Although the special licenses entitled these doctors to treat military families around the world, they didn't allow them to practice in civilian hospitals and clinics, even in Oklahoma.

`It was not a license to practice on the citizens of Oklahoma in independent practice such as a regular state license is,' says a 1992 letter from the Oklahoma medical board to a military doctor explaining why she couldn't use her special license to practice on Oklahoma civilians. `It may be true that you can practice as well as any doctor in Oklahoma; however, the legal requirements for licensure must be met to assure to the public that this is true.'

A Dayton Daily News analysis found that of 113 special licenses issued by the Oklahoma State Board of Medical Licensure and Supervision, at least 77 went to doctors in the Army, Navy and Air Force, which together have about 13,500 doctors.

The other doctors with special licenses worked in Indian clinics, mental hospitals and prisons. A few licenses went to doctors working at veterans' hospitals or at labs that handle organs for transplants.

Nearly all of the 77 military special licensees either failed the state licensing exam used nationwide, called the FLEX, or had no evidence in their files that they ever took it. The FLEX exam tests both basic science and clinical knowledge and is designed to ensure that doctors meet the minimal requirement to practice medicine in the United States. The FLEX was only recently replaced by the United States Medical Licensing Examination.

Thirty of the 77 failed the FLEX exam three or more times, the maximum number some states permit before requiring doctors to get additional training.

Between 76 percent and 90 percent of graduates of U.S. and Canadian medical schools pass the FLEX on their first try.

Even Oklahoma medical officials acknowledged that the FLEX is a measure of a physician's competence.

In answering a letter from Moscoso, Carole Smith, executive director of the Oklahoma medical board until earlier this year, explained why he couldn't use his special license - the one Oklahoma gave him to treat military patients - to treat civilians:

`As to denying you the right to prove you are a competent physician, the FLEX was designed to assess exactly that, and you failed that examination 14 times.'

Failing exams wasn't the only problem the 77 special licensees had.

Some didn't finish post-graduate training required for civilian doctors. At least two were eventually court-martialed, one for molesting patients and the other for failing to record prescriptions. Another was released from active duty after military officials discovered problems with the records documenting some of his training.

Department of Defense health officials said they were unaware that a number of military doctors practiced without proper licenses.

"Our initial review has confirmed your report that some military physicians hold a special license from the state of Oklahoma," says a letter from John F. Mazzuchi, deputy assistant secretary of defense for clinical services. "We have initiated action to correct this situation."

Mazzuchi said he also asked the surgeons general of each service to verify the licenses of all doctors.

"We thought an Oklahoma license was an unrestricted license," said Lt. Gen. (Dr.) Ronald R. Blanck, the Army's surgeon general. "We're writing a letter to that state board and saying: Don't do it. That's dumb."

Blanck said he identified eight Army doctors with special licenses. None, he said, will be allowed to treat patients until they're properly licensed.

Although military officials denied knowing about the special licenses, three doctors told the Daily News the military directed them to go to Oklahoma.

Dr. Kang gave the newspaper a June 1988 memo from the Air Force surgeon general's headquarters in Washington, D.C., titled "Oklahoma Medical Licensure for active-duty physicians." The memo, which included the address and telephone number of the Oklahoma medical board, informed Air Force doctors that Oklahoma was granting licenses to doctors practicing in the military for at least five years without requiring them to pass a national licensing exam.

The memo also thanked an Air Force colonel for "pioneering this initiative."

"I know I failed a lot of times," said Kang, who remains in the military and is stationed at Barksdale Air Force Base, La. "This was approved by the government ... All the military hospitals sent a letter to take the examination (in Oklahoma).

"Until today, nobody told us to get full license."

Special license holders put in charge

Some special licensees weren't just allowed to practice medicine, they were allowed to supervise other doctors.Ubaldo P. Beato Jr. was made `chief of flight medicine' at Sheppard Air Force Base, Texas, based on his `broad knowledge of the concepts and facets of preventive medicine in the United States Air Force,' says a letter from the Air Force to the Oklahoma board.

At the University of Santo Tomas in the Philippines, Beato failed anatomy, microbiology and pathology. He failed a class on parasites twice. In the seven years he spent in medical school, he made grades of 85 or above in only three subjects: legal medicine, medical nutrition and preventive medicine.

Beato failed state medical exams at least six times.

Dr. Feliciano Ramos Acorda was the chief radiologist at three Air Force bases. But the Ohio medical board refused to give him a license in 1980 because he failed the FLEX three times in Ohio and three times in two other states.

"That test was not easy," said Acorda, currently a lieutenant colonel at California's Edwards Air Force Base. "Fortunately for us, Oklahoma offered us this."

Dr. Gualbert M. Sanchez, a colonel who served at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, is the medical consultant to the Pentagon on matters regarding disability, retirement and separation of Air Force members. He works at the Air Force Personnel Center Headquarters at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas.

Sanchez, too, got his medical degree from the University of Santo Tomas in the Philippines, where he failed 11 of 50 subjects listed on transcripts he submitted to the Oklahoma board. Those subjects included physical diagnosis, preventive medicine, gynecology, pediatrics and advanced pathology.

Almost half the subjects he took in medical school - 24 of 50 - he passed with a grade of 75, and he only made grades of 80 or above in four subjects: religion I, religion II, legal medicine and medical nutrition.

In a September 1996 annual evaluation, an Air Force colonel at Randolph rated Sanchez "outstanding" in each of four categories, including medical knowledge.

Rafael Roberto Sandoval-Diaz, an Army colonel, was a director at the nurse anesthetist school at Fort Hood, Texas. A graduate of the University of Honduras Medical School, Sandoval-Diaz failed the FLEX twice.

Oklahoma board saw no danger

Oklahoma board officials said special licenses were the brainchild of the late Mark Johnson, former secretary of the Oklahoma board and a military doctor in the Philippines during World War II.Most of the requirements were the same as other states except applicants didn't have to pass the FLEX or other national licensing exam.

The FLEX exam came in two parts: One part tested basic science (book knowledge) and the other part tested clinical (hands-on) knowledge. Johnson was concerned that military doctors might fail the basic science portion of the exam because they'd been out of school and had not taken a test in years, said Dr. G.C. Zumwalt, board secretary.

"We felt like the military members and their families were not going to be in danger if (the doctors without regular licenses) kept practicing,' said Carole Smith, former executive director of the Oklahoma board. `Nobody at that point in time was willing to give (medical) licenses in their states unless they met certain criteria.'

MILITARY RESPONSE"Our initial review has confirmed your report that some military physicians hold a special license from the State of Oklahoma. We appreciate your calling this to our attention. We have initiated action to correct this situation. In addition, I have requested that the Surgeions General inquire as to the licenses held by all physicians on active duty and to ensure that they are in keeping with our policy."

John F. Mazzuchi, Ph. D., Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense, Clinical Services

|

"It is not a licensing exam. It's a re-exam," said Dr. Henry G. Cramblett of Columbus, a former president of the Federation of State Medical Boards who helped write the SPEX and the FLEX exams. "Of course I have a problem with that because it wasn't designed for that purpose."

Oklahoma never limited its special licensees to doctors who hadn't taken a test in a long time. Several were recent medical school graduates. Others failed the SPEX, too, and still others failed the part of the FLEX that tested clinical knowledge.

Dr. Bernard W. Deas Jr., commander of the Army health clinic at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico in 1993, failed the FLEX in 1971, while in his senior year of medical school. He failed it again in 1988 in Georgia.

Dr. Stephen J. Eshman, a native of Lima, failed the FLEX once during his residency training and another time four months after completing his residency.

Sanchez, the Air Force consultant to the Pentagon, made a failing grade of 73 on the SPEX. Sanchez said the Oklahoma medical board converted the score to a passing grade.

Flawed rationale behind program

The rationale the Oklahoma medical board used to grant the special licenses - that applicants may have forgotten a lot of book knowledge - didn't take into account that the test results may have accurately identified doctors with marginal skills.Dr. Gregory S. Tengco failed or got unsatisfactory for 21 of the 32 subjects he took at universities in the Philippines from 1954 to 1958. Tengco, who also failed the SPEX in Oklahoma and failed national licensing exams in three other states, was chief of radiology at three Air Force hospitals.

Tengco, who left the military in 1995, said that he eventually repeated the college courses he failed. Asked how he knew about the Oklahoma licenses, he said, "The Department of Defense sent us a letter."

Dr. Charles Floyd, a Navy captain, repeated his first year of medical school at the University of Kansas. In 1979, two years after graduating, he failed both portions of the FLEX, and he failed the SPEX with a 63 - 12 points below the minimum score. The Oklahoma board flagged his application, stating: `Numerous examination failures warrants discussion in meeting.'

The Navy made him director of mental health at the Naval Hospital in Puerto Rico.

Dr. Jonathan H. Chang, another graduate of the University of Santo Tomas in the Philippines, failed the FLEX 14 times and failed the SPEX once, scoring a 70.

He was denied licenses in Colorado and Illinois; he got a special license from Oklahoma.

In 1978, the same year Illinois refused to let him practice in that state, Chang joined the Army as an anesthesiologist and was sent to Germany.

In responding to a complaint, Chang disclosed to the Oklahoma medical board a memo marked `Confidential,' which says a patient of Chang's identified only as `Ms Kissy' died while under his care in 1982, while Chang was stationed at Fitzsimmons Army Medical Center near Denver.

`I was unable to bring (her) back from anesthesia,' Chang wrote in the memo.

Army records show Chang was the chief anesthesiologist at Fitzsimmons until 1983 and the chief at Fort Ord, Calif., until 1992, when he was transferred to Madigan Army Medical Center near Tacoma, Wash. At Madigan, the Army revoked his clinical privileges because of `unsatisfactory performance of his duties,' Oklahoma state board records show.

The Army put Chang back in anesthesia training, but he failed to complete it. During its review in 1992, the Army found something else: A document showing Chang completed residency training in anesthesia at Loyola University in Chicago was "determined to be erroneous," says a letter from an Army colonel.

Chang had been in the Army 14 years, and he held a Oklahoma license for more than two years. But neither the Army nor Oklahoma authorities had known the document was false.

Oklahoma medical board records show the Army didn't revoke Chang's hospital privileges until 1993, a full year after learning about the forged training records. He left active duty in 1994, but he remained in a pool of doctors available for recall. Oklahoma revoked his license in October 1995.

Doctors' problems not just academic

Like Chang, several other special licensees had problems unrelated to their academic qualifications.Dr. Franklin B. Waddell's Oklahoma medical board file not only noted three FLEX failures, but it also included three malpractice claims filed at Langley Air Force Base in Maryland.

A 1982 claim for $20 million involved the care of infant twins, one who died and the other who suffered brain damage. A $10 million claim in 1985 alleged a woman's left ovary was removed without her consent.

In the third claim, also filed in 1985 and asking for $1,100, a woman eight weeks pregnant who complained of severe stomach pain andbleeding said she was told to take Tylenol and to come back in 72 hours. The next day, the woman was admitted to a civilian hospital, where doctors diagnosed her as having a ruptured fallopian tube and chronic pelvic disease.

The Air Force faulted Waddell in only one of the cases, saying the woman who lost the ovary should have had her cancer diagnosed sooner, adding that she "suffered no damage" due to the delay. In the case of the woman with the ruptured fallopian tube, the Air Force blamed the woman for not returning to the military hospital as directed when her symptoms did not improve.

Dr. Zehera Nizam Ali Khan, a graduate of the Osmania Medical College in India, was denied a medical license by Florida. The reasons: She only had one year of post-graduate training completed eight years earlier, had "marginal grades" in medical school, was rated poor in basic medical knowledge and had `several episodes when she was not honest and she actually lied,' medical board records show.

She failed the state licensing exam in Georgia, prompting the medical board to write:

`If you have failed the FLEX three times anywhere in the United States, you are required to take one year of additional training approved by the board before taking the FLEX in Georgia again.'

Khan, an Army major, failed the exam at least eight times, but she was still given a special license in Oklahoma. Her latest assignment listed in board records was `chief physical exam section' at Fort Benning, Ga.

In a 1988 memo recommending Khan for an Oklahoma license, an Army lieutenant colonel at Fort Benning, said this about Khan:

`As a military officer, Dr. Khan has been a vital part of our organization, both in her clinical skills and in ... supervising the timely performance of over 200 physicals per day.'

Two years later, Oklahoma denied her a regular license, citing `the applicant's difficulty in obtaining a passing score ... indicates a lack of educational and clinical training.'

Khan now holds a regular Georgia license and works as a civilian doctor at Fort Benning. She said the military directed her to Oklahoma.

"When I wanted to quit the Army, they said: No, you can take the SPEX exam." Dr. Kang failed the state license exam 30 times, beginning in 1973. Here are some of his results. A 75 is needed to pass. Dr. Gregory S Tengco failed or got unsatisfactory in 21 of 32 subjects at universities in the Phillippines from 1954 to 1958.

Part 5 - Double Standards of Care

The armed services voluntarily participate in a national registry of doctors linked to medical malpractice but under rules that drastically restrict the number of physicians who get reported.