Both doctors had histories of malpractice |

By Russell Carollo DENVER - Leigh Clark was bleeding to death on the operating table when Dr. Phillip L. Mallory got the emergency call at home and rushed to Fitzsimmons Army Medical Center. |

Sometimes, Leigh Clark just hangs out, watching TV at her house in Toledo. SKIP PETERSON DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

Clark was supposed to have a routine 45-minute procedure to diagnose the cause of her severe abdominal pains. But instead of making a small incision just through her ab- domen wall, Dr. Daniel Lim punctured the main artery carrying blood to her right leg.

Clark, who now lives in Westerville, near Columbus, survived. But at a price: eight more surgeries, months of pain and a body forever marked with scars. "A 16-year-old gymnast is now permanently crippled," a confidential Army record says. `It's very hard,' said Clark, a University of Toledo student.`It's really, really hard to soak it up when you're 16 years old.'

What happened to Leigh Clark that July day in 1993 was more than an isolated mistake by a single doctor. She was the victim of a health care system that operates without the most significant safeguards protecting civilian families from medical malpractice.

Her surgeon had no license to practice in the state where the operation took place; Colorado refused to give him one. The chief of gynecology at the hospital didn't have a license to practice in the state either. Both doctors had histories of medical malpractice. And equipment vital to her care was nowhere to be found in the operating room. Information on cases such as this usually is kept from the public. That's because Congress passed a law protecting information on military doctors - information routinely released by civilian medical boards. "I was officially ordered to return the records,' said Clark's father, Randall Clark, a nurse at the hospital. "They said they were government records, and we weren't allowed to have them.' The Dayton Daily News pieced together details of the case through dozens of interviews in Washington state, Georgia, Colorado and Ohio. Reporters also reviewed hundreds of pages of documents from courthouses and medical boards in Canada and the United States. Medical board files included previously confidential Army records stamped on every page with a warning: `Unauthorized disclosure carries $3,000 fine.'

Leigh Clark braces herself in the doorway while making her way outside without wearing her leg brace. She cannot walk without her brace and often has to hop from point to point. SKIP PETERSON DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

* Dr. Lim wasn't licensed in Colorado, where Fitzsimmons is located. The state denied him a license based on problems he had before coming to Fitzsimmons. The problems involved his treatment of two other young female patients with conditions nearly identical to those of Clark, who had a fetus lodged in a fallopian tube. Civilian doctors must be licensed in the states where they practice.

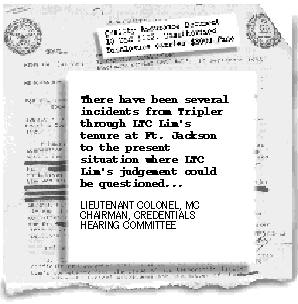

* The Army cited "several reported incidents" at two previous bases in Hawaii and South Carolina, suggesting "that, at times, Lt. Col. Lim's compulsiveness in managing patients has been less than ideal."

* Lim said his suspension by the Army at the South Carolina hospital wasn't reported to the computer database Congress established to weed out problem doctors. Identical cases involving civilian doctors are required to be reported, but the military doesn't have to follow the same rules.

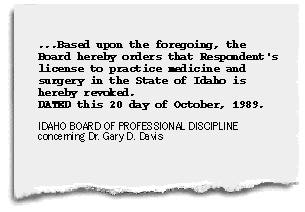

* Dr. Gary Davis, the man ultimately responsible for Clark's care as the hospital's chief of gynecology, also did not have a Colorado license. Davis, instrumental in bringing Lim to Fitzsimmons despite concerns from other hospital officials, had his own hospital privileges suspended in Arkansas years earlier. He also had his license revoked in one state and suspended for 18 months in another state.

* The Army was in critical need of OB-GYNs. Lim said the Army recruited him because of the shortage. Years later, an Army commander, notifying him of a disciplinary action at a previous base, noted that downsizing left the service short on doctors with that speciality. And the chief of surgery at Fitzsimmons said the Denver hospital was short-staffed when it hired Lim.

Lt. Gen. Ronald R. Blanck, the Army surgeon general, said privacy laws prevented him from talking about specifics of the Clark case. But he said he sympathized with the family. "My heart goes out to her," he said.

The surgeon: Dr. Daniel Lim

The path that brought Lim to Leigh Clark's operating table started on the other side of the world, in his native South Korea. His career included stints in the South Korean army, Canada, Iowa, Michigan, Hawaii, South Carolina and Illinois - a portion of the time spent studying and practicing not gynecology or surgery, but psychiatry.In 1985, shortly before his 55th birthday, Lim joined the U.S. Army, leaving behind a 15-year-old practice in Davenport, Iowa.

"I was tired of solo practice," Lim said, adding that the Army recruited him and other doctors like him. "They sent us all this literature, all three services. They needed more OB-GYNs in the military, I guess. At the time, I was 55. They still said they needed me."

His first assignment was Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii. There, Lim said, he was responsible for teaching dozens of residents to do a form of exploratory surgery called laparoscopy - the same surgery he would attempt unsuccessfully on Clark.

Included in Lim's licensing file at the Medical Board of California is a report from a high-ranking Army medical official who found "several reported incidents' beginning at Tripler in which "Lim's compulsiveness in managing patients has been less than ideal'

"That's my fault for causing the injury, but any vascular surgeon should have been able to fix it. They made me a scapegoat for this case."

DR. DANIEL LIM |

Dr. Gary Davis, the man ultimately responsible for Clark's care as the hospital's chief of gynecology, also did not have a Colorado license. Davis, instrumental in bringing Lim to Fitzsimmons despoite concerns from other hospital officials, had his own hospital prvileges suspended in Arkansas years earlier. He also had his license revoked in one state and suspended for 18 months in another state. |

As with the Clark case, doctors suspected both women at Fort Jackson had tubular pregnancies - a fetus lodged in a fallopian tube rather than in the womb. One had symptoms identical to Clark's: severe abdominal pains.

In one case, Lim ordered laboratory work `but did not wait to see the results, which would have pointed toward a diagnosis of ectopic (tubular) pregnancy,' the Army records say. `The results of your failure to pursue these diagnostic results is that the patient ruptured an ectopic pregnancy and required surgery.'

Lim said the woman left the hospital and went AWOL before results came in.

In the second case, a 19-year-old woman showing symptoms of a tubular pregnancy came into the hospital just before Lim was to take a vacation.

"Because you were planning to go on leave, you failed to come in to examine the patient,' Army records say. "Again, the patient required surgery for an ectopic pregnancy.'

Lim said there were other doctors to cover for him.

Military records obtained by the Colorado medical board show the Army found Lim provided substandard care to the two patients and prohibited him from "evaluating, diagnosing or treating patients with first-trimester pregnancies."

In notifying Lim of the action, an Army commander said Lim would be recommended for separation from active duty. He noted that the decision placed a "burden on the hospital at a time when the Army is downsizing and there is a shortage of OB-GYN practitioners.'

Lim appealed, arguing he did nothing wrong. Several months later, the commander of the Army Medical Corps restored his privileges.

The Army, Lim said, never reported its initial finding to a computer database created by Congress to screen job applicants at hospitals across America. Unlike the military, which has its own reporting rules, civilian hospitals must report all disciplinary actions, even those later changed.

The chief of gynecology: Dr. Gary D. Davis

Like Lim, Dr. Davis came to Fitzsimmons Army Medical Center with a history of disciplinary action and allegations questioning his ability to practice medicine. Davis, the chief of gynecology at Fitzsimmons, had his hospital privileges suspended in Arkansas for performing an operation without permission. Later, he lost his Idaho license and had his Alabama license suspended for 18 months after several patients accused him of malpractice.He joined the Navy and later joined the Army as actions were about to be brought against his practice.

In April 1979, Baptist Medical Center in Little Rock suspended his privileges to treat patients after an investigation into undisclosed allegations.

"I was not very smart. I tied a tube in a lady who had an ectopic pregnancy," Davis said during an interview at his new assignment in Washington state. He said that there was nothing wrong with what he did but that he did it without first getting permission from a hospital committee.

Two months after his privileges were suspended at Baptist Medical Center, in June 1979, Doctors Hospital in Little Rock suspended Davis for undisclosed reasons. He resigned. Davis said he never practiced at that hospital.

After leaving Arkansas, Davis went into the Navy as a lieutenant commander and was sent to Subic Bay in the Philippines. He stayed two years, leaving in 1981 to open an office in Lewiston, Idaho.

In Idaho, he accumulated more complaints.

Davis was sued five times by patients he treated between 1983 and 1987. At least three resulted in settlements to patients, including an undisclosed settlement with a woman who sued for more than $3million after her daughter's death.

Another patient, Marna Vinup, said she went to Davis' Lewiston office in 1986 complaining of weak spells. Vinup, who was 37 at the time, said Davis diagnosed her ovaries as being swollen and full of cysts and removed them.

Months later, Vinup said, she showed her medical records to her family doctor. "He said my ovaries were just fine" and didn't need to be removed. Vinup sued and eventually settled with Davis' insurance company for about $25,000.

In 1988, the Idaho Board of Medicine began legal action against Davis, accusing him of several instances of medical malpractice and of failing to disclose his problems in Arkansas.

But by then, Davis had left town.

Davis denied ever leaving a job because legal actions were pending against him. He blamed the Idaho board investigation on a former business partner who reported him because he was angry over financial dealings with Davis. The Idaho lawsuits, he said, were no more than nuisance suits, all either dismissed or settled for small amounts.

Idaho, Alabama act against Davis

In 1987, the Army gave Davis the rank of major and sent him to Martin Army Community Hospital at Fort Benning, Ga., where he was made chief of obstetrics.In October 1989, Idaho revoked his medical license. In September 1990, the Alabama medical board suspended his license for 18 months based on the Idaho action. But Davis, needing only one license from any state to practice in the military, still had a medical license from the Georgia medical board, which refused to revoke it.

|

Board spokeswoman Kara Jones said the board didn't reach the same conclusion as the two other medical boards. Asked if Georgia sent investigators to Idaho as part of the review, Jones said, `We don't have investigators who go from state to state.'

Davis said the Army briefly put his privileges in "abeyance" as it reviewed the allegations against him.

Months after the Army review, Clarrissa Garrigus went to the clinic Davis oversaw, complaining that her 32-week-old fetus had quit moving. During the next several weeks, Garrigus said, doctors should have identified her pregnancy as high-risk and taken steps to save the unborn child. They didn't, she claimed, because Davis never instructed the other doctors how to identify the signs of high-risk pregnancies. "He was the chief," she said.

Several of the other doctors were not OB-GYNs but were filling in because of shortages at the hospitals, Davis said.

"We supervise them, but you can't very well be every place at once," he said, adding that the Army had allowed them to practice as OB-GYNs.

At 36 weeks, Garrigus' baby was born dead.

In July 1992, Garrigus filed a legal claim against the Army, which the Army denied. She sued in federal court, and the Army settled the case for $480,000.

"You don't (forget). You can't.... You feel there's something missing every day," said Garrigus, who since has had another son. "When I pick up my son from school, I know there should be two of them."

'The credentials committee just looked the other way'

In the fall of 1992, just weeks after Garrigus filed her claim, the Army transferred Davis to Fitzsimmons, making him chief of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and putting him in charge of training Army doctors in the residency program.Not long after his arrival, Davis met with hospital officials to decide whether to grant credentials to a doctor slated for transfer to Fitzsimmons. That doctor was Daniel Lim.

Dr. Mallory, who attended the meeting as the hospital's chief of general surgery, said the committee discussed the allegations against Lim at Fort Jackson and his qualifications in coming to a larger hospital.

"He (Davis) recommended to the credentials committee that Lim be credentialed," Mallory said. "He wasn't the final approval authority, but he was able to persuade the committee."

"The credentials committee just looked the other way. They were short-staffed."

Still, based on Lim's treatment of the two young women at Fort Jackson, the Colorado Board of Medical Examiners denied his application for a license. "While your privileges were later reinstated, the reviewing appeals committee concurred with the initial reviewers that your care and treatment were substandard," the board concluded.

But as an Army doctor, Lim didn't need a Colorado license to practice in the state. He still held licenses in at least two other states, and on Feb. 8, 1993, the Army officially transferred Lim to Fitzsimmons.

Davis did not deny playing a part in bringing Lim to Fitzsimmons, but he said he had concerns about Lim, too, and recommended he be supervised. He acknowledged the hospital needed OB-GYNs at the time. "I was short of everything," he said.

"I didn't fall on my sword" to prevent Lim from being hired, Davis said, adding that he probably should have.

Dr. Blanck, the Army's surgeon general, acknowledged that Davis may have made a mistake when he hired Lim.

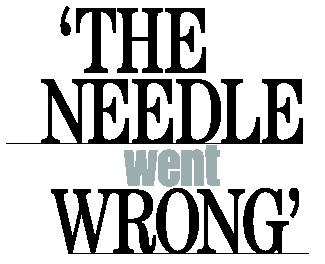

Leigh Clark's operation: 'The needle went wrong'

Five months after Lim's transfer, 16-year-old Leigh Clark was baby-sitting when she doubled over from pain in her abdomen.Her parents brought her to Fitzsimmons, where her father had been stationed as an Army nurse since 1985. Davis was the head of the hospital's OB-GYN clinic, where she underwent several tests.

Army records show that three tests confirmed Clark was pregnant, but doctors didn't know whether her pain came from an appendicitis or a tubular pregnancy. They decided on exploratory laparoscopy, a routine procedure in which tiny holes are made just through the abdominal wall. Through one hole a miniature camera is inserted. Through another hole, C02 gas is pumped, inflating the abdomen and allowing surgeons more room and better vision while probing inside.

Leigh Clark talks with one of her friends, Laura Rako, at the Dorr Street Cafe where Leigh works part-time. She spends a lot of time here with her friends, whom she feels very close to. SKIP PETERSON DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

Clark's abdominal cavity deflated unexpectedly, and a C02 tank needed to reinflate her properly was not available. With her abdominal cavity not fully inflated, surgeons could not see as well.

"Standard of care in such circumstance would have been to abandon the laparoscopic procedure" and open the patient up with standard surgery, Army records show.

But Lim continued and "blindly inserted" a surgical instrument into Clark, an Army commander wrote in a memo to Lim, adding, "This is a blatant error."

Lim acknowledged that he missed the incision during the operation, but he said doctors should have been able to repair the damage.

"I was assisting the resident. ... Somehow the direction was wrong," Lim said, adding that the position he had taken next to the resident may have caused the confusion. "The needle went wrong."

Still, Lim said, other doctors should have been able to repair the damage. "That's my fault for causing the injury, but any vascular surgeon should have been able to fix it. They made me a scapegoat for this case."

By the time Mallory arrived, the operating room was in chaos.

"The Clark girl was white as a ghost," Mallory said. "Lim didn't talk to me. He didn't tell me what happened. That's what made this thing so dangerous."

Mallory made a synthetic bypass around the damaged artery, but the leg had been deprived of blood and oxygen so long that amputation seemed the only option.

"Because of your gross error in judgment, a 16-year-old gymnast is now permanently crippled ... (and) will undoubtedly lose her right leg below the knee,' the Army medical commander wrote.

After the operation: 'So much pain'

When Clark woke up from the operation, she knew something had gone wrong. Several of her relatives had come from Ohio to be at her bedside."I couldn't understand why I was in so much pain," she said. "It was like somebody was taking a knife and swirling it around in my leg. I was on morphine. I had my own machine (to administer it). It didn't do anything."

She said Davis came to her hospital room while she was still in pain.

"He just came in and started lecturing me about how I was 16 years old and needed to be on birth control,' she said. "I told the nurses I didn't want him in my room ever again, and that was the last time I saw him.'

Clark stayed in the hospital for nine weeks, undergoing eight more operations. Her leg was swollen three times its normal size, and the pain seemed to never stop. She even considered suicide.

Leigh Clark uses a brace to walk. Her leg are foot are not straight and her foot does not touch the ground correctly. SKIP PETERSON DAYTON DAILY NEWS |

In one operation, surgeons cut large gashes deep into either side of her calf muscle to provide the leg room to swell. Three to four times a day, nurses would change the dressing from the operation.

"It took eight nurses and my dad to hold me down," she said. "I'd scream to the point that I'd pass out."

The damage to Leigh's leg

Clark kept her leg, but barely. From the knee down, her right leg is a third the size of her left leg, with a scar running nearly all the way from the knee to the ankle.Her foot is twisted and nearly useless. It took eight months before she could get even the slightest movement from her toes. Only with the use of a thick plastic brace can she put any weight on her leg, and even then she limps.

Davis was promoted to full colonel, one promotion away from the rank of general. After Fitzsimmons closed in 1995, he was transferred to Madigan Army Medical Center near Tacoma, Wash., one of the Army's largest hospitals. He was made chief of gynecology and urogynecology and director of clinical investigation for the obstetric and gynecology department. He also was put in charge of teaching young doctors.

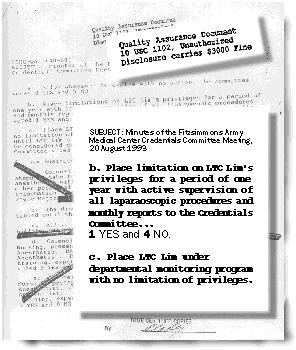

Weeks after Clark's surgery, the Fitzsimmons hospital's Credentials Committee voted 4-0 to monitor Lim but to place no limitations on his practice there. The hospital commander, along with a higher-ranking Army medical commander, rejected that decision and permanently restricted Lim's practice.

But, as Lim had done at Fort Jackson, he appealed to a higher authority, the Department of the Army. The Army ordered that his patient charts be reviewed in the future, but it allowed him to practice `without limitation of privileges.'

Lim left the service in March 1995 and now lives in Bath, N.Y., where he holds a state license to practice medicine.

The Clarks hired Stephen A. Justino, a Denver attorney who only a year earlier worked for the Army at Fitzsimmons and was on the hospital committee that identified problem doctors.

`They were ready to settle the case as soon as we started doing the investigation," Justino said.

Clark's father, retired Master Sgt. Randall Clark, said that after he filed the lawsuit, the Army relieved him of his duties as a nurse at Fitzsimmons and ordered him transferred him to Korea. Asked about the transfer, Lt. Gen. Blanck said: "That's dumb, insensitive, and it's not what we're about."

Clark, who served in Vietnam, said he also was ordered to return his daughter's medical records, which were being used by his attorney to prepare for litigation.

"Once a person files a military malpractice claim against the military, the military does everything it can to make the person's life miserable," said Clark, who returned with his family to Westerville.

The Army paid the Clarks $987,786 immediately - $5million over Clark's lifetime.

The money, she said, will never repay what she lost.

This summer, she went to Mexico and wore shorts for the first time.

"People stared. You kind of get used to it," Clark said. "I'm so jealous of people who can run or rollerblade. It's little things like that."

She also lost something else.

"I wanted to be like my dad. I used to want to be in the Army," she said. "It killed my entire belief in the military."

Part 3: Too Many Patients Too Little Time

The William Beaumont Army Medical Center in Texas was targeted for more medical malpractice claims in a 10-year period than any other military health facility in America, but the problems there occur to some degree in every military hospital.